- 416 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Virtual Reality in Geography

About this book

Virtual Reality in Geography covers "through the window" VR systems, "fully immersive" VR systems, and hybrids of the two types. The authors examine the Virtual Reality Modeling Language approach and explore its deficiencies when applied to real geographic environments. This is a totally unique book covers all the major uses and methods of virtual reality used by geographers. The authors have produced a CDROM that comes with the book of virtual reality images that will be a fascinating companion to the text. This book will be of great interest to geographers, computer scientists and all those interested in multimedia and computer graphics.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1 Virtual reality in geography

An introduction

Peter Fisher and David Unwin

A question of definition?

This is a book about virtual reality (VR) in geography. We assume that most people reading it will have an understanding of the term ‘geography’, but unfortunately although, and perhaps because, ‘virtual reality’ is a very trendy term, neither ‘virtual’ nor ‘reality’ is either well defined or strictly appropriate. For example, much more helpful would be the earlier notion of ‘alternative reality’ or the more recent one of ‘virtual worlds’.

In preparing this book we struggled to find a definition of VR that met the aspirations of those involved in editing and writing the major chapters. The most acceptable definition that could be agreed on was that:

Virtual reality is the ability of the user of a constructed view of a limited digitally-encoded information domain to change their view in three dimensions causing update of the view presented to any viewer, especially the user.

This definition is catholic, but it is one which encapsulates the essence of all visualizations that can legitimately be called virtual reality. More prosaically, it also brings in all the participants in this workshop and others into a unified framework.

We suspect that to many people VR is associated with games parlours, films, etc., involving many and varied but always very specialised computer technology using hardware such as headsets, VR theatres, caves, data-gloves and other haptic feedback devices. All of these are associated with experiences where users are immersed in a seemingly real world that may be entirely artificial or apparently real. This is the high-technology, immersive image of VR, but it seems that:

- there have been widely-reported ergonomic issues from using these immersive environments such as feelings of user disorientation and nausea,

- producers have an enormous ability to deliver the necessary information for virtual worlds to the public using the simpler technology of the World Wide Web, and

- immersive equipment remains expensive to the average user.

In practice, therefore, and in common with much of the current writing on VR, most of the applications described in this book make use of a ‘through-the-window’ approach using conventional interaction methods, basic, if top-of-the-range, desktop computers, and industry-standard operating systems.

VR is of enormous commercial importance in the computer games industry and similar technology is often used in training simulations. Currently, many academic disciplines are involved in developing and using virtual worlds and this list includes geography (Brown, 1999; Câmara and Raper, 1999; Martin and Higgs, 1997). The most obvious geographical applications are in traditional cartography, for example, in creating navigable, computer-generated block diagrams, and especially in the same discipline re-invented as scientific visualization (Cartwright et al., 1999; Hearnshaw and Unwin, 1994). Second, because of the importance of the spatial metaphor in those worlds, basic concepts of cartographic visualization of the world are fundamental to our ability to navigate and negotiate almost any applications of VR. Basic geographical concepts have thus much to contribute to the more general world of VR. Third, some geographers are developing concepts that extend VR environments into completely artificial realms such as abstract data realms (Harvey, Chapter 22) and even completely imaginary, but interesting, Alpha Worlds (Dodge, Chapter 21).

Why this book now?

Our purposes in convening the expert workshop on which this book is based were three:

- To highlight the fact that geography in general, and cartography in particular, has much to offer those developing VR environments. This is a result of the historical concern in these disciplines with the rendering and communication of spatial information.

- To demonstrate that VR is a technology that overtly requires the construction of a world to be explored. In so doing, it necessitates a statement of how that world is constructed, and therefore makes clear, at least to informed users, the multiple representations which may have been possible for the same subject. In many ways VR relates back to traditional concerns within geography as to the nature of representation, the primacy of particular representations, and the tensions between alternative constructions which we share with colleagues.

- To review current state-of-the-art work in the field of VR applications in the spatial sciences.

These purposes are underscored by an entry in the Benchmarking Statement for Geography in Higher Education prepared for the Quality Assurance Agency for Higher Education in England, Wales and Northern Ireland which states that:

Geographers should show knowledge and critical understanding of the diversity of forms of representations of the human and physical worlds. Maps are one important form of representation of the world, and geographers should be conversant with their basic cartographic, interpretational and social dimensions. However, geographers should show a similar depth of understanding of other representational forms, including texts, visual images and digital technologies, particularly geographic information systems (GIS).

and, one might add, virtual reality.

To meet these objectives, this book has been structured into four major sections:

- positioning VR in technology and computing,

- explorations of virtual natural environments,

- constructions of virtual cities,

- other virtual worlds which may be imagined, or constructed as windows onto unreal worlds.

How it was put together

Initially each section was built from papers submitted to a workshop organised by the editors in association with the Royal Geographical Society with the Institute of British Geographers Annual Conference held in Leicester in January 1999.

Most papers were presented at that workshop, but have subsequently been extensively revised in the light of discussion at the workshop. Most importantly, authors collaborated in preparing introductions to each section in which they put their individual contributions into a wider context, providing an overview of other relevant work. Reading these introductions on their own will provide a good introduction to the field, but we hope that this will only serve to hone an interest in the remaining chapters, and in the potential of this technology for representations in geography.

References

Brown, I.M. 1999. Developing a virtual reality user-interface (VRUI) for geographic information retrieval on the Internet. Transactions in GIS, 3, 3, 207–20.

Câmara, A.S. and Raper, J.F. (eds). 1999. Spatial Multimedia and Virtual Reality. London: Taylor and Francis.

Cartwright, W., Peterson, M.P. and Gartner, G. (eds). 1999. Multimedia Cartography. Berlin: Springer.

Hearnshaw, H.M. and Unwin, D.J. (eds). 1994. Visualization in Geographical Information Systems. London: John Wiley and Sons.

Martin, D. and Higgs, G. 1997. The visualization of socio-economic GIS data using virtual reality tools. Transactions in GIS, 1, 4, 255–66.

Part I

Introduction to VR and technology

2 Geography in VR

Context

Ken Brodlie, Jason Dykes, Mark Gillings, Mordechay E. Haklay, Rob Kitchin and Menno-Jan Kraak

VR in geography

Given its ubiquity, researchers could be forgiven for believing that a concise and coherent definition of virtual reality (VR) exists, bolstered by a carefully-charted developmental history, a comprehensive list of the ways in which VR can be most profitably applied, and, perhaps most fundamentally of all, an encompassing critique of the technology.

As noted in our editors’ Introduction (Chapter 1), reading the chapters in this book will show quite clearly that such a consensus doesn’t exist even in the restricted field of academic geography. The diversity of technologies and approaches employed by the authors of this first section demonstrates this point clearly. It would appear that there are as many ‘virtual realities’ as there are researchers actively involved with VR. This has not prevented these authors from offering definitions or frameworks derived from a bewilderingly wide range of fields (including computational mathematics, education, cartography and aesthetics), based on technologies, or by using purely pragmatic approaches. The latter are the most commonly encountered and are founded upon the assertion that if you are engaged with a representation to the point where your body is responding involuntarily to it as though it were the real world, then you are probably dealing with VR! In such a scheme the definition of VR is reduced to the creation of representations that are so convincing that were a virtual glass to fall from a virtual hand, the user would involuntarily reach out to catch it (Brodlie and El-Khalili, Chapter 4).

Defining VR

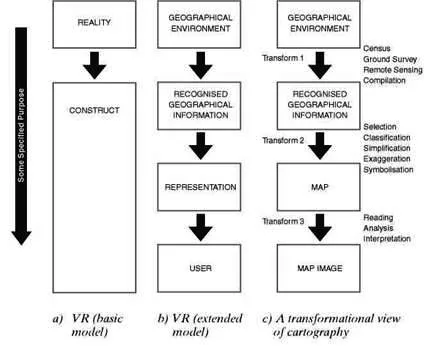

Without wanting to anticipate these more detailed discussions, by way of introduction to this section we offer a very broad definition of the technology that emphasises the common elements in our work. We agree that VR is a form of human–computer interface (HCI). More specifically, in each case the process of using VR, or producing a VR simulation, involves the creation of a construct on the basis of a source reality, in our case the geographical environment (Figure 2.1a). This simple model can be expanded to include two other critical factors common to each of our applications. These are the geographical information derived from the environment and the users themselves (Figure 2.1b). To readers who have a background in cartography, it will be apparent that if we replace the terms ‘representation’ and ‘user’ with ‘map’ and ‘map image’ respectively, our framework for VR corresponds to the traditional cartographic process viewed as a series of transformations (Robinson et al., 1996, after Tobler, 1979; Figure 2.1c).

Figure 2.1 Schematic representations of VR and cartography.

a) VR identified as creation of construct from reality; b) An expansion of the schematic shows the series of information transformations involved in producing VR; c) A transformational view of cartography (after Tobler, 1979; Robinson et al., 1996).

So far our attempt to create a framework for our VR applications has got us little further than mere semantics. Are we to define VR simply as a subset of cartography? Is there anything that serves to distinguish approaches such as VR from traditional and more established means of representing the world?

We argue that VR is distinct from traditional cartographic transformations. What makes it different is the nature of the relationship between the representation (map) and user (map image). In such a formulation the emphasis of VR, as a form of HCI, is on the process linking the representation and its user. This transformation involves high levels of interaction between user and representation. In our schematic this feature of VR is represented by a bi-directional arrow flowing between the map and the user rather than the single, unidirectional arrow of cartography. This relationship is also stressed by our alternative terminology in the constructs used in the transformational view of cartography. In our VR applications the emphasis is on a ‘representation’ defined more broadly than the traditional ‘map’, and the physical user, rather than their ‘map image’. This is because the real world affordances that we provide in VR to facilitate the transformation between representation and map image (involving the processes of reading, analysis and interpretation) form the crux of our applications. What is more, unlike any other mode of cartographic representation, in VR the level of engagement between map and user can be varied. In our schematic this is indicated graphically by the length of the arrow relating the two. If a single feature can be said to characterise VR, it is the ability to embed the user fully within the representation, permitting the kind of real world representation desired by, but unavailable to, Tobler when he noted that

Any given set of data can be converted to many possible pictures. Each such transformation may be said to represent some facet of the data, which one really wants to examine as if it were a geological specimen, turning it over in the hand, looking from many points of view, touching and scratching.

(Tobler, 1979: 105)

Ways in which VR can achieve this interactive, real-world interface between recognised geographical information, representation and user are shown schematically in Figure 2.2.

The degree to which the user and representation are collapsed is dictated by the precise use to which a given application of VR is oriented. As this volume shows, the breadth of applications of VR even within a single discipline such as geography are enormous. They cover the whole spectrum of approaches and users from the initial exploration of a complex data set by an individual expert in an attempt to find patterns, through to the final graphical presentation of results to a wider audience lacking in the same level of expertise. For example, if a VR model is constructed to test the effects of alcohol intake on drivers or to train surgeons in delicate techniques, the level of user immersion in the vir...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contributors

- Acknowledgements

- 1: Virtual reality in geography: An introduction

- Part I: Introduction to VR and technology

- Part II: Virtual landscapes

- Part III: Virtual cities

- Part IV: ‘Other’ worlds

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Virtual Reality in Geography by Peter Fisher,David Unwin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Civil Engineering. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.