![]()

Part One

An Informal History: How the Library Got Where It Is

![]()

1

The History through Spofford

What do we have here? Without doubt the greatest collection of knowledge, memory, and experience ever assembled in one space since the beginning of man. The ancients tried to achieve such a collection in their library at Alexandria and (given a somewhat shorter memory and not so much knowledge and experience) almost brought it off. Strangely enough, we are probably as near totality today as they were then. Like the Greeks and Egyptians, we have assembled as much as the world knows about all the cultures of the world, not just our own. Do you want a fact? a song? a formula? a philosophy? Nowhere in the world can it be found more efficiently. One-stop knowledge. For whom? Gathered why?

We owe this monumental pile of facts to the work habits of the Founding Fathers. They were book oriented from the very first. Most of them were lawyers and shared their profession's traditional respect for the printed word in codes and precedents; most of the few who were not lawyers were philosophers and pamphleteers, nourished on the literature of the Enlightenment. For them, thinking meant first reading—and then, as a rule, writing more themselves.

It started with the first Continental Congress in 1774. As unlikely as it might seem, almost the first action taken by that body was to secure borrowing privileges from the Library Company of Philadelphia. That book collection was already one of the largest in the colonies, and it was housed with rare good fortune at the other end of Carpenters' Hall where the delegates were meeting. The Library Company graciously resolved "to furnish the Gentlemen . . . with the use of such Books as they may have occasion for during their sitting, taking a Receipt for them."

Thirteen years and a revolution later, when many of the same delegates met again in that incredible summer of 1787, they relied on the same Library Company collection, and when they assembled in 1789 as the First Congress of the United States, they found themselves in the same building as the New York Society Library. The legislators promptly secured access to that library's 4,000 volumes, but there followed a minor argument that came to nothing at the time but that presaged endless debates from that time to this.

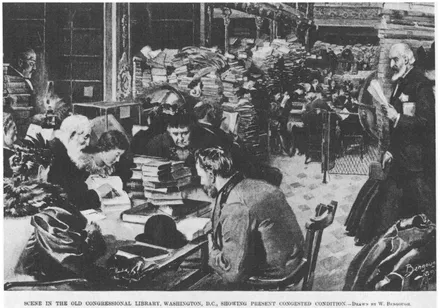

By 1876 Librarian Ainsworth Spofford reported that there was no space left in the Library proper and that "books are now, from sheer force of necessity, being piled upon the floor in all directions." The situation had reached impossible proportions by 1897, as depicted in this drawing by W. Bengough, which appeared in Harper's Weekly on February 27, 1897. Spofford is seen on the far right, emerging from his desk area with papers in his hand; David Hutcheson, Assistant Librarian, is on the left holding a lamp.

The discussion was precipitated by Elbridge Gerry, distinguished signer of the Declaration of Independence and delegate to the Constitutional Convention. On August 16, 1789, he urged that a Committee be appointed to select "a catalogue of books" for Congress to use and to estimate the cost of and the best way to come by them. Acting with precedential dispatch, such a committee was indeed formed eight months later, and in only seven weeks it delivered a report to the House. It noted that the delegates were "obliged at every session to transport to the seat of the general government a considerable part of their libraries," and "having due regard to the state of the treasury," it recommended that $1,000 worth of books be bought at the outset and that $500 a year be spent to purchase books thereafter.

The motion generated vast apathy on the part of the Congress but splendid outrage from the taxpayers. A typical demur is the following from the Independent Chronicle of Boston, May 13, 1790:

The late motion respecting the "Library" for Congress is truly novel—could it be supposed that a measure so distant from any thing which can effect the general purposes of government, could be introduced at this important period? . . . How absurd to squander away money for a parcel of Books, when every shilling of the Revenue is wanted for supporting our government and paying our debts?

... It is supposed that the Members of Congress are acquainted with history; the laws of nations; and possess such political information as is necessary for the management of the affairs of the government. If they are not, we have been unfortunate in our choice. ... It is supposed that the members are fully competent for these purposes, without being at the expence of furnishing them with Books for their improvement.

. . . The people look for practical politicks, as they presume the Theory is obtained previous to the members taking their seats in Congress.

That was the last anyone ever heard of the committee or its recommendations, but "the people's" position was to reappear.

By 1791, the government had returned to Philadelphia, and although the Library Company had moved into its own quarters, Congress recovered access to the Company's volumes. In this manner, for nearly twenty years, the Founding Fathers managed to keep a broad information base easily accessible, and it was used daily as an integral part of their legislative activities—without having to "squander away money" or to further distress the treasury.

With the spring of 1800, we come to the formal founding of the Library and the first attempts to decide whose library it was and what kind of a library it was to be. The decision was forced on the members of Congress by Hamilton and Jefferson's Great Compromise, which placed the new capital in a marshy area just south of the Great Falls of the Potomac. The time had come to fix a permanent seat of government, and funds were appropriated to move the personnel of all three branches of government from Philadelphia to the new District of Columbia.

On April 24, 1800, President John Adams signed the transfer bill, the fifth section of which legislated the Library of Congress into being. It called for the purchase of $5,000 worth of books and the "fitting up of a suitable apartment for containing them." The purchase was to be made by the secretary of the Senate and the clerk of the House; the books were to be used by both houses of Congress. A Joint Committee on the Library was established to assist in the selection of volumes and the establishment of rules. Neither the executive branch nor the judiciary was to be given access. It was strictly Congress's library.

The Library's first home was in an upper room of the new Capitol Building, and it soon received its second (and almost its last) legal underpinning. In January 1802, Congress passed a law that has been called the "charter of governance" for the new library. It called for the appointment of a Librarian to be made "by the President of the United States solely," note, not by the legislature whose books they were. Possibly because this step had already created a breach in the separation of powers, the President and the Vice-President were granted borrowing privileges. The Librarian was to be paid at a rate not to exceed 2 dollars a day, and all moneys spent on the Library were to be under the review of the joint committee, which now consisted of three members from the Senate and three from the House.

President Thomas Jefferson promptly appointed a close personal friend, one John James Beckley, as the first Librarian of Congress. The new Librarian and his committee began by querying bibliophiles throughout Washington for suggested purchases, and among those asked was Jefferson himself. Jefferson sent an extensive list "in conformity with your ideas that books of entertainment are not within the scope of it, and that books in other languages, where there are no translations of them, are not to be admitted freely." He avoided "those classical books, ancient and modern, which gentlemen generally have in their private libraries, but which can not properly claim a place in a collection made merely for the purpose of reference."

The President did soften his reference-only rule in one area:

The travels, histories [and] accounts of America previous to the Revolution should be obtained. It is already become all but impossible to make a collection of these things. Standing orders should be lodged with our ministers in Spain, France and England and our Consul at Amsterdam to procure everything within that description which can be hunted up in those countries.

That suggestion, in fact, appears to have been a corollary to the numerous recommendations for maps suggested by almost everyone. The thirst for maps, it turns out, was not for finding tools with which to deal with an empty continent, but for proof against expected litigation when "the new countries" began to fill up. It is clear that everyone expected the space to be Balkanized (France, England, and Spain still held great portions of it), and the Founders wanted proof of contemporary settlements, boundaries, and "presence." Every recommended map was pursued, and most of them were acquired.

One of the more colorful recommenders at the time was the chairman of the Joint Committee, Senator Samuel Latham Mitchill. Mitchill was a medical doctor from New York, who was referred to by his colleagues as a "veritable chaos of knowledge," and he is remembered for providing one of the better justifications for the Library: He urged the acquisition of "such materials as will enable statesmen to be correct in their investigations and, by a becoming display of erudition and research, give a higher dignity and a brighter luster to truth."

If that was Mitchill's justification, what did the committee think it was trying to accomplish? It would appear that the first Joint Committee believed it had three options. First, and obviously, it could build a small collection of working tools similar to what the legislators knew back in their homes and law offices: ready-reference, statutes, and books on the philosophy of the law. Second, the new collection could be a "public library" for the members. The concept of a public library at that time meant a private, usually subscription, collection, which was available to the mercantile community in a city, to the social elite, or to a college community. In terms of the legislators' experience in the towns they came from, such a library would have a broader, more balanced collection, which would be used by the members of the legislature or even all the government leaders, and it would include cultural and recreational volumes as well as working books. And finally, the committee could have begun what would in fact be a national library. This would serve the federal government in Washington, but it would also act as a cultural and historical archive for the young country. Several of the European nations had such a national library, and the early leaders of the nation were both proud of the new government's achievements and eager to take on the ornaments of the older, established nations.

So which option did the committee choose? The "public library." That answer will come as news to the present-day library community, because for the last 100 years, we have been taught that the Library of Congress started as a reference collection. We now know that the early historians were misled by their study of the book purchase orders for the first decade. (Among them, incidentally, they found such intriguing lists as that of June 1800, in which 152 titles in 740 volumes were ordered from England and were rather quickly delivered to the United States in eleven hair trunks. The London bookseller noted that he "judged it best to send trunks instead of boxes, which after their arrival would have been of little or no value." Taking the dealer's sensitivity to the needs of an underdeveloped country at face value, Congress instructed the secretary of the Senate "to make sale of the trunks in which the books lately purchased were imported." The 152 titles were rigorously limited to law, political science, economics, and history, and there was a special case filled with rolled maps.)

But recent scholars have concentrated on an inventory of the Library as it looked in 1812 instead of what was ordered—and we now know precisely what was in the collection as opposed to what was purchased. The difference is the result of a carefully selected acceptance of gift volumes, which were presumably begged from members of the government. All of the volumes "which gentlemen generally have in their private libraries," as Jefferson had said, were indeed in that first collection, apparently given by the Library's patrons. The result was a well-balanced "public library." From its very beginning the Library of Congress collections had run the full spectrum of factual and creative writing.

By 1812, the Library had 905 titles in 3,000 volumes, arid almost every volume had been printed in England. The books were arranged by general subjects, and history and biography was the largest group with 248 titles. Law, as might be expected, was next with 204, but less expected was the rest of the span. There were 105 titles in geography and topography—including Jeffrey's American Atlas (London, 1800), Jedidiah Morse's American Geography (London, 1794), and Welde's Travels Through the States of North America (London, 1800)—16 titles on natural history; 24 titles on medicine, surgery, and chemistry; and 42 on poetry and the drama and works of fiction. The titles in the last group sound as appealing as a good browsing collection should: Mrs. Elizabeth Inchbald's British Theatre in 25 volumes, Burns's poems, Shakespeare's plays, four volumes of Rabelais, the complete works of "Nichola Machiavel," 12 volumes of Samuel Johnson, 14 volumes of Henry Fielding, Pope, Virgil, Aeschylus, Cicero, Scott's Marmion, and 7 volumes of Mrs. Inchbald's Collection of Farces. There were 33 dictionaries and one set of Diderot's Encyclopédie in 35 volumes (Paris, 1751), which had cost the Librarian $216 and was the most expensive title in the collection. By 1812, the Joint Committee had spent $15,000 total and had acquired a tight, well-balanced library that would have been a credit to any institution.

Then, in the spring of 1813, an event occurred that had a profound effect on the Library. An American force fought its way into the capital of Upper Canada (then called York, now Toronto) and set fire to the Parliament Buildings. The troops destroyed the archives, stole the plate from the church, and burned the parliamentary library. The British sought revenge, firmly targeting the Capitol and its Library, but here our otherwise straightforward history of the Library stumbles onto an overgrown part of the path. The fact is that, from this distance in time, we are just not sure what happened next.

We do know that on August 18, 1814, a fairly substantial British force sailed up the Chesapeake Bay, eager to get even for the burning of York. The War Department in Washington, having a fair idea of what was in the invading commander's mind, called out all the ablebodied men in the city and on August 19 (a Friday), put them into the Maryland fields.

On Saturday and Sunday, the working archives of the State and Treasury Departments were evacuated from the city. On Sunday afternoon, someone remembered the congressional papers and files, and one of the clerks of the House was instructed to find transportation to evacuate the legislative materials. The executive branch had already appropriated all the local wagons, so the clerk had to go outside the city, where he ultimately found a cart and four oxen at the farm of one John Wilson, who lived six miles out of town. The cart arrived at the Capitol after dark on Monday, and the clerk and Assistant Librarian (too old to be caught in the militia draft) began to load it, first with the manuscript papers of the clerk's office and then with books from the Library. These materials were taken "on the same night, nine miles, to a safe and secret place in the country," according to the Assistant Librarian and the clerk writing on September 15.

The cart was loaded and moved, loaded and moved, back and forth, throughout Tuesday and until Wednesday morning (August 24), when the British appeared in Washington and promptly set fire to the Capitol. The two men admitted with sorrow that "the last volumes of the manuscript records of the Committees of Ways and Means, Claims and Pensions, and Revolutionary Claims" were lost, and "a number of the printed books were also consumed, but they were all duplicates of those which have been preserved." There is no question but that the Capitol itself was gutted.

On September 21, barely four weeks later, Thomas Jefferson wrote a letter to his friend Harrison Smith, a newspaper publisher in private life and, in public life, commissioner of the revenue. Writing from Monticello, Jefferson opened his letter, "I learn from the newspapers that the vandalism of our enemy has triumphed at Washington over science as well as the arts, by the destruction of the public library, with the noble edifice in which it was deposited." Jefferson noted that it was going to be exceedingly difficult to replace the Library "while the war continues, and intercourse with Europe is attended with so much risk." He described his own collection of "between nine and ten thousand volumes," which he had acquired while living in Europe and subsequently when he was President. The contents, he noted, mainly "related to the duties of those in the high concerns of the nation."

He explained that it had been his intention to give the Congress "first refusal" of his library at its own price on his death, but in view of the present difficulties, this might be "the proper moment for its accommodation." He offered to sell the library in annual installments but was ready to make it available at once. "Eighteen or twenty wagons could place it in Washington in a single trip of a fortnight." He appended a detailed catalog of its contents and declared, "I do not know that it contains any branch of science which Congress would wish to exclude from their collection; there is, in fact, no subject to which a Member of Congress may not have occasion to refer."

On October 3, Smith told Congress of the offer. On October 7, the Joint Committee on the Library offered a resolution authorizing and empowering it to "purchase . . . the library of Mr. Jefferson." The committee sent a delegation to Monticello, where the collection was counted and found to contain 6,487 volumes. Appraisers costed the volumes at $3 each for the common-sized books, $1 for the very small ones, and...