Introduction

The history of the Holy Roman Empire before the mid-sixteenth century provides a challenge to our established models of state formation and diplomacy.2 Historians have long struggled to understand this enormous and fragmented polity populated by many smaller political entities. Generally the Empire of the late medieval and early modern periods has attracted quite negative judgements for its alleged failure to become a ‘nation-state’, or to conform to the supposedly normal pattern of European political development.3 The models that have attempted to make sense of it have tended to apply concepts fashioned elsewhere and tried to fit them to the local evidence. For example, the patrimonies and powers of the Empire’s autonomous princes, bishops, nobles, and cities have been understood as ‘territorial states’ or ‘territorial lordships’—Territorialstaaten, Landesherrschaften—which constituted a kaleidoscopic expanse that filled central Europe.4 These little states are thought to have been ruled primarily by princes and other noble lords,5 but some ‘city-states’ and urban ‘territories’ have also received attention.6 The corollary of this ‘state-oriented’ view of the Empire’s political make-up is that, already by the late middle ages, these nascent territorial states possessed their own emerging sovereignty or Landeshoheit,7 and conducted their own diplomacy and foreign policy, or Außenpolitik.8

There are a number of problems with this view of the Empire in the long fifteenth century as a mosaic of little territories. Far from being discrete states-in-the-making, all of the political powers in the Empire overlapped and depended on one another in structural ways which precluded totally independent courses of action, and prevented the development of uncontested jurisdictions, administrative organs, and sovereign conceptions of power which might allow for autonomous diplomatic activity.9 Structures of tenure, like fiefs, or Lehen, and pledges, or Pfandschaften, were not arranged hierarchically in pyramids of power flowing downwards from sovereign princes, but held by interlocking networks of actors, including urban and clerical elites as well as princes and lesser nobles.10 Underpinning the legitimacy of every member of the imperial elite, from the greatest of the prince-electors to the smallest of the Imperial cities, was an overarching polity, the Holy Roman Empire itself, with its multipolar division of power between the monarchy and the various factions amongst the estates, and its much-used but relatively ineffective administrative organs, the imperial aulic and chamber courts (Hofgericht and Kammergericht) and the chancery.11 The idea of the Empire as a unitary political framework continued to animate and inspire its inhabitants, as evinced by imperial themes in visual and material artefacts, as well as the abundant records of regular meetings of imperial elites and the countless imperial charters of privileges that survive in numerous archives from the late medieval and early modern centuries.12 Against this background, the interaction between the overlapping powers in the Empire was not equivalent to the more clearly ‘international’ diplomacy between, for instance, the kings of England and France in the fifteenth century and beyond.13 Although the most powerful imperial princes and cities maintained relations with external monarchs, their dealings with one another within the Empire’s borders were of an altogether more interconnected and localized nature.

In fact, there is one school of thought, pioneered by Otto Brunner in the 1940s to 1960s, which asserts that there was no diplomacy whatsoever in the Holy Roman Empire, and in Christendom more generally, before the Reformation. Brunner railed against what he saw as the anachronistic use of concepts such as ‘state’ and ‘sovereignty’ by late medievalists.14 The powers of Europe, and especially the powers within the Empire, exercised only ‘lordship’ (Herrschaft) over patrimonially- and communally-defined ‘lands’ (Länder) in Brunner’s view.15 Christian exercisers of Herrschaft did not conduct foreign policy with one another, because they were not foreign to one another—they were integrated within the legal-political framework of the Land, the Empire, and ultimately Christendom as a whole, in which only the pope could engage in anything approaching ‘diplomacy’.16 Instead, relations between powers were governed by customary states of friendship—Freundschaft, amicitia—or enmity—Feindschaft, inimicitia. Consequently, there were also no real wars in Christendom according to Brunner, only states of enmity that allowed for the feud, which was governed by strict legal norms.17 This scheme assumes that all of the Empire was homogeneous and that its elites obeyed an immutable code of relations derived self-consciously from ‘Germanic’ and Christian values, which is rather unconvincing.18

This chapter proposes a middle way between these two extremes, namely that the Empire was a collection of proto-sovereign territorial states which conducted diplomacy like other European powers, or else that the imperial elites’ complex interactions consisted of a unified aristocratic code of conduct. One avenue of exploration for making sense of political interaction between powers within the Holy Roman Empire in this period lies with the theme of this volume: culture, and more specifically, political culture. In recent decades the concept of ‘political culture’ has been applied fruitfully to many later medieval and early modern contexts. In the broadest sense, the study of political culture entails situating political processes within ‘the “complex whole” of social organisation’.19 More specifically, Barbara Stollberg-Rilinger and other early modernists of the ‘Münster school’ of the ‘cultural history of politics’ have emphasized the value of socioanthropologically-inflected analysis of the interactions of power-wielders in pre-modern Europe as a means of decoding the political significance of certain actions and behaviours and identifying the (sometimes overlapping, sometimes competing) symbolic and material systems within which they were embedded.20 By taking into account the practices that constituted the sociocultural norms of power-wielders in the Holy Roman Empire, it becomes possible to identify what was distinctive about its political structures and culture, and the ways in which interactions within the Empire differed from other modalities of political activity, including diplomacy between discrete polities.

It is possible to reconstruct the interactions of many political actors in the Holy Roman Empire, and the structures and norms which shaped these interactions, from the later medieval and early modern evidence. These primary sources, produced by the administrations of princes, bishops, towns, and others, display some striking shared patterns. These groups made use of the same documentary forms and formulae; discourses and practices of lordship; ritualized approaches to feuding and warfare; methods of mediation and arbitration at judicial diets; performative and symbolic modes of communication; and contractual associations such as alliances and leagues.21 This last activity was particularly important, because associations provided a formal framework within which these other aspects of customary political interaction played out.22 The archives of what was once the southern Holy Roman Empire are full of treaties of association, which, in addition to promising military support, regulated forms of negotiation (for example, by specifying who should arbitrate in any disputes that might arise between members of the association).23 The most important and distinctive form of interaction and negotiation in the Empire was the constant use of assemblies and diets, or Tage, at which alliances would be considered, disputes would be discussed, feuds would be resolved, and arbitrational decisions would be rendered.24 Quite often these Tage were arranged within the framework of an association, be it a local society of knights, a league of towns, or a large trans-regional peace-union (Landfriede). Sometimes Tage were not attended by princes, bishops, lords, or city mayors or guild masters in person, but by representatives called Boten or Botschaften, words which might be translated into English as ‘messengers’, ‘envoys’, ‘negotiators’, ‘deputies’, and even ‘ambassadors’, depending on the context.25

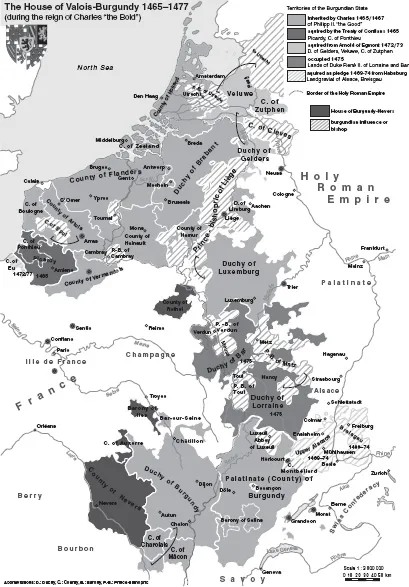

Viewed through the lens of political culture, these forms of interaction that characterized the Holy Roman Empire look neither like those of distinct kingdoms, nor like those of familial noble networks. This political culture, defined by contractual associations and institutionalized and ritualized negotiations, had many diplomacy-like features, but it was clearly different from the court-centric forms of diplomacy that were increasingly being practised by the proto-sovereign kingdoms and principalities of fifteenth-century Italy and western Europe. One way to explore the extent to which the political culture of the Empire differed from, or overlapped with, developing forms of diplomacy elsewhere in Europe is to find practitioners of both forms of political interaction. Here the Upper Rhine region, which spanned the south-western lands of the Empire, provides some instructive examples. This area consisted of hundreds of overlapping powers, ranging from princes such as the Tyrolean line of dukes of Austria and the margraves of Baden, to bishops, such as those of Strasbourg and Basel, to Imperial cities, like the metropolises of Zurich and Strasbourg, as well as many far smaller autonomous towns on both banks of the Rhine and in Swabia.26 The Upper Rhine was thoroughly integrated within the political networks and culture of the Upper German space which formed the core of the Holy Roman Empire. Yet it was also in close proximity to the expanding territories of the Valois (and later Habsburg) dukes of Burgundy, with whom the Upper Rhenish powers interacted with increasing regularity in the course of the late fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. As we shall see, contact between imperial actors and Burgundy generally had ‘international’ characteristics under the four Valois dukes, Philip ‘the Bold’ (1363–1404), John ‘the Fearless’ (1404–1419), Philip ‘the Good’ (1419–1467), and Charles ‘the Bold’ (1467–1477).27 This diplomatic contact tended to involve the formal appointment of ambassadors, the use of multilingual mediators, and the reliance of the Burgundian administration on local diplomatic agents, who might be promoted to official ambassadors in certain circumstances. The result was that some prominent Upper Rhenish figures doubled as Burgundian clients, working with Burgundian diplomats or even acting as ambassadors themselves, even as they engaged in customary forms of association and negotiation with their German-speaking neighbours. Three examples of these Burgundian clients-cum-local political actors will be examined in this chapter. It will then be possible to conclude with some brief reflections on what their careers might mean for our conceptions of diplomacy at this early and highly complex end of the early modern world.