This is a test

- 508 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This book is devoted to a comparison of the governmental and economic institutions of north and south zones of Viet-Nam; that each zone has its own set of economic and political troubles and that both sides are engaged in military efforts which may well overwhelm them in the end.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Two Vietnams by Bernard Fall in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Asian Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

One

The Common Ground

1

The Physical Setting

"LIKE—two rice baskets at the opposite ends of their carrying pole" that is the way Vietnamese often describe their country, which uncoils in the form of an elongated S for more than 1,200 miles, from the 9th parallel north to the 26th, covering 127,300 square miles (about 330,000 square kilometers).

As one approaches it from the air—whether from Hong Kong to Hanoi, the northern capital; or from Bangkok or Manila to Saigon, the southern capital—one sees vast expanses of lush vegetation or endless rice fields stretching the metallic mirror of their flooded surfaces to the horizon during the rainy season, or presenting the velvety green of growing rice at other times. About 80 per cent of the country is covered with trees or brush, and 49 per cent of that is high-stand tree cover or outright jungle. The remainder consists of the open plains of the rice-bearing deltas.

It is those deltas—that of the Mekong in the south and of the Red River (Song-Coi) in the north—which indeed are the "rice baskets" of the country. Their vast alluvial plains (the Mekong Basin covers three-fifths of neighboring Cambodia as well) produce in good times 9 million tons of rice: 5 million and more in the south, and 4 million in the north. In addition, a whole series of smaller deltas, often built around rivers less than 100 miles long, dot the shore line of Central Viet-Nam: Thanh-Hoa, Ha-Tinh, Quang-Ngai, Binh-Dinh, Khanh-Hoa, etc.

The "carrying pole" of those rice baskets is a series of mountain chains whose watershed roughly constitutes Viet-Nam's western border with Laos and Cambodia and is known as the Annamite Cordillera. Its mountains vary in height from more than 10,000 feet close to the Chinese border to about 4,000 feet as they drop in a sheer cliff into the sea near Cape Varella, to the north of the Khanh-Hoa plain

Thus, Viet-Nam can be divided into eight natural regions—three low-lying plains, three mountain areas, and two that fall between the two other categories in altitude and configuration: (1) the Red River and Mekong deltas and the smaller Central Vietnamese deltas; (2) the Annamite Cordillera, the Thai Hill area of northwestern Tongking, and the northeastern Tongking mountain area; and (3) the North Vietnamese Midlands (Moyenne Région), which forms a wedge of terraced hills and soft-shouldered mountains to the north of the Red River Delta; and, finally, the vast Southern Mountain Plateau (still referred to by its French initials PMS, for Plateaux Montagnards du Sud), which covers two-thirds of all Viet-Nam south of the 17th parallel.

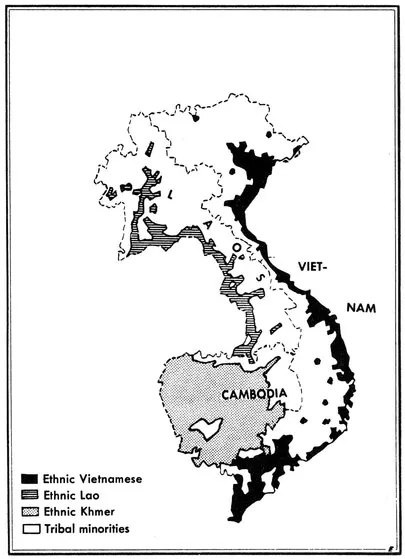

As can readily be seen, this is a country with no geographic unity whatever, and since the bulk of its population exists by cultivating rice on lands irrigated by gravity or by a system of often still primitive pumps and sluices, they live to an overwhelming extent in the tiny lowland pockets, leaving the vast uplands to ethnically alien mountain tribes. The results, in terms of human geography, are startling.

Whereas in the United States an average of 60 persons lives on a square mile of land, the average, in the Red River Delta, is 1,236— reaching in Nam-Dinh Province the fantastic figure of 3,800 inhabitants to the square mile. While in the PMS, often fewer than 5 inhabitants can be found per square mile, the neighboring Central Vietnamese delta of Binh-Dinh has an average of 1,380 to the square mile. In the open plains of the fertile Mekong Delta, the population figure is far less heavy; few areas reach a figure of 500 to the square mile, and many provinces have about 260 inhabitants to the square mile.

Thus, of Viet-Nam's 30.5 million inhabitants in 1962 (16.5 million in the zone north of the 17th parallel and 14 million south of the parallel), close to 29 million live on about 20 per cent of the national territory, while the remaining 1.5 million roam—and the term can be applied literally, since many of them are at least seminomads— over more than 100,000 square miles of plateau and mountain areas. In American terms, this would mean that 175 million Americans were settled between the Eastern seaboard and the Appalachians, while another 8 million would have the rest of the country, all the way to the Pacific Ocean, to themselves.

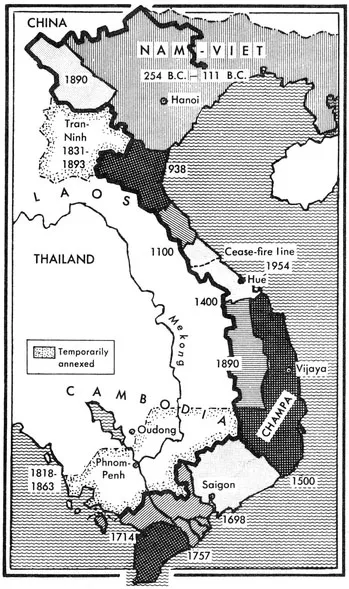

It is obvious that such a situation would have far-reaching social and economic consequences. In Viet-Nam, the chaotic geography has conditioned the whole political and historical outlook of the country to this very day. For 1,000 years, the history of the Vietnamese people was one tenacious "Long March" to the south, from one small rice-bearing delta to the next, until the wide-open plain of the Mekong was reached and put to the plow.

In spite of their highly diversified racial origins, the Vietnamese today are largely an ethnically and culturally homogeneous people. The whole Indochinese peninsula appears to have been inhabited at first by an Austro-Indonesian population not unlike that which inhabits New Guinea today. Those aboriginal inhabitants were pushed farther and farther into the mountain areas of their country by Thai and Mongolian invaders from the north and by seafaring Indians from the west. The Thai migration began probably around 2000 B.C. and has not yet come to a complete halt.* The Indian influx culminated in the creation of the Khmer empire, which still survives in the present-day kingdom of Cambodia, and in the creation of the kingdom of Champa, which was subsequently destroyed by the Vietnamese.

The present-day Vietnamese language, with its blending or monotonic Indonesian and variotonic Mongolian elements, bears further evidence of the racial heritage of the Vietnamese. A flourishing indigenous Bronze Age culture—the Dong-Son civilization—existed in Viet-Nam about 200 B.C. According to Joseph Buttinger,1 "in the Red River valley the New Stone Age was only beginning to give way to the Age of Bronze when Chinese imperial expansion suddenly thrust the Vietnamese onto a higher level of civilization." Very recent archaeological findings suggest that Bronze Age culture may be even older by a few centuries than hitherto believed.2

The various Chinese occupations that followed over the next 1,000 years also left a profound physical imprint upon the Vietnamese, while in the deep south of the country, intermarriage with the Cambodian inhabitants produced yet a different ethnic strain. The mountaineers who were pushed back into the hills have held onto their original culture to this day. In the north, the Thai, Muong, and Meo dominate the whole back country and their high cultural level— in many cases equal to that of the lowland Vietnamese—makes them a political factor that cannot be ignored. In the south, the more primitive tribes of the PMS, inaccurately called "Moi" ("savages"), have also maintained their elaborate tribal and social structure against heavy odds. Although their exact numbers are not known, spot censuses have shown that there may be as many as 1 million southern mountaineers living in the PMS area. For the northern mountain areas, the 1960 census gives a figure of 2,600,000 mountaineers.

Two other important ethnic minorities exist in Viet-Nam, and both live south of the 17th parallel: the Khmer (Cambodians) and the Chinese. The Chinese as rulers or residents have lived with the Vietnamese for 2,000 years. Although recent nationality laws enacted in South Viet-Nam have given Vietnamese citizenship to these Chinese, the ethnic and economic reality of the presence of 1 million Chinese—merchants, butchers, bankers, and rice millers—cannot be disregarded. The half-million Cambodians (or Khmer Krom, "Southern Khmer," as they are called in Cambodia), whose presence in South Viet-Nam is a living reminder of how recently Viet-Nam colonized the area, are concentrated in and west of the Mekong Delta. It is likely that they will disappear as a separate ethnic entity within a few generations. Realistically, the present Cambodian leadership—though defending the minority rights of the Khmer Krom— seems to have abandoned all thought of liberating the area by force.3

Thus, it can be reliably estimated that in 1962, 15 per cent of Viet-Nam's population consisted of ethnic minorities, about equally divided between both zones.

A third physical reality that is as important as the unequal distribution of Viet-Nam's population is the unequal distribution of its mineral and agricultural wealth. Accidents of climate and geology make the two zones of Viet-Nam not economic rivals, but, in normal times, perfect complements to each other. The northern zone pos

MINORITY AND MAJORITY POPULATIONS IN INDOCHINA

sesses all the mineral wealth necessary, and in economically sufficient and accessible quantities, for a viable light- and medium-industrial base; the south has an output of highly diversified agricultural products more than adequate to meet the demands of the interior market and supply cash exports.

There is enough cheap high-grade anthracite and coal in the north to solve all Viet-Nam's industrial fuel problems and leave a comfortable margin for economically competitive exports; and in South Viet Nam, rice, rubber, spices, and textiles could likewise take care of the needs of the whole population and still leave highly valued export surpluses.

In each zone, the sealing-off at the 17th parallel has resulted in the diversion of costly human and material resources into projects designed to alleviate the shortages created by the absence of complementary deliveries from the other area. In North Viet-Nam, an intensive agricultural-production drive has been under way for several years to compensate through secondary crops, such as corn and manioc, for the absence of yearly deliveries of 250,000 tons of southern rice. In South Viet-Nam, considerable state capital and French economic aid has gone into the opening of a coal mine at Nong-Son, which has a total yield of perhaps 3 million tons, while North Viet-Nam's coal fields could easily produce 3 million tons a year and have been producing 2.5 million tons all along. In any case, both sides are a long way from self-sufficiency, let alone economic balance. But the northern regime continues laboriously to plant rubber trees in a few terrain pockets whose climate resembles that of the warm Mekong Basin, and the southern regime prospects just as laboriously for mining deposits in soils whose geological structure leaves little basis for optimism as to future discoveries of great mineral deposits.

In both zones, this imbalance has created a heavy dependence upon external aid. In the north, the heavier ravages of war from 1946 to 1954 added to the area's usual problems; and in the south, though less seriously hit, the absorption of 860,000 refugees constituted a priority problem of crucial importance. And today, whatever modest gains had been made beyond mere postwar recovery have been jeopardized by the spreading guerrilla war.

It is in this difficult physical environment that the Vietnamese people, fighting against overwhelming odds for more than 2,000 years, carved for itself a niche along the eastern rim of the Indochinese peninsula.

* For example, in 1961-62, several Black Thai tribal groups, fleeing Pathet-Lao Communist elements, descended into the Mekong Valley and crossed over into Sayaboury Province in an exact repetition of the age-old process of migration of those tribes.

2

A Glimpse of the Past

MUCH of Viet-Nam's history before 200 B.C. is shrouded in legend —but so is much of Europe's past beyond the Mediterranean basin. A kingdom known as Van Lang and, briefly, Au Lac, seems to have existed between 500 and 207 B.B.,1 apparently covering most of what is today China's Kwang-tung Province and North Viet-Nam. The latter, as will be seen, has been a border zone more than once in Viet-Nam's long and stormy history.

Conquered by Chinese generals who had broken with the Ch'in emperors and had adopted the mores of the "barbarians," Au Lac became known as "Nam-Viet" ("South[ern country of the] Viet").* As often later on in Vietnamese history, the small state could maintain its integrity only when its huge neighbor fell on hard times, which happened more often than is usually believed. With the rise of the stronger Han in China, Nam-Viet was slowly pushed out from Kwang-tung into its North Vietnamese redoubt, in 111 B.C., the victorious Han crushed the young Vietnamese state, and save for a few brief but glorious rebellions, it remained a Chinese colony for more than 1,000 years.

Viet-Nam became a Chinese protectorate ruled by a governor and subdivided into military districts. By the beginning of the first century A.D., the country had absorbed, along with many Chinese settlers— a great many of them refugees from the Han dynasty—much of what was worthwhile in the culture of the occupying power: the difficult art of rice planting in artificially irrigated areas, Chinese writing skills, Chinese philosophy, and even Chinese social customs and beliefs. But—and in this the Vietnamese are almost unique—they succeeded in maintaining their national identity in spite of the fact that everything else about them had become "Chinese." Opposition to Chinese rule built up as the Chinese presence became more ubiquitous and brutal. Finally, what could be called a routine "occupation incident," the execution of a minor feudal lord, brought about a conflagration, in 39 A.D., Trung Trac, the wife of the slain lord, and her sister Trung Nhi raised an army that, in a series of swift sieges, overwhelmed the Chinese garrisons, which had grown careless over the years. In 40 A.D., the Vietnamese, much to their own surprise, found themselves free from foreign domination for the first time in 150 years and the Trung sisters were proclaimed queens of the country.

Naturally in so huge an empire, Chinese reaction was slow, but when it came, it was effective. Old General Ma Yuan began his counterattack in 43 A.D., and the Vietnamese troops of the two queens made a fatal error: They chose to make a stand in the open field against the experienced Chinese regulars, with their backs against the limestone cliffs at the edge of the River Day—not far from the place where Communist General Vo Nguyén Giap was to pit his green regulars against French Marshal de Lattre's elite troops 1,908 years later. The result was the same in both cases: The more experienced regulars destroyed the raw Vietnamese levies. The two queens, rather than surrender to the enemy, chose suicide by drowning in the nearby river. "Sinization" now began in earnest, with Chinese administrators taking the place of the traditional Vietnamese leaders. Two more rebellions took place. One, in 248 A.D., also led

VIET-NAM'S IMPERIAL MARCH 111 B.C.-1863 A.D.

by a...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- PREFACE

- Contents

- Part One: THE COMMON GROUND

- 1. THE PHYSICAL SETTING

- 2. A GLIMPSE OF THE PAST

- 3. COLONIAL INTERLUDE

- 4. WHITE MAN'S END

- 5. “DOC-LAP!”

- Part Two: REVOLUTION IN THE NORTH

- 6. THE RISE OF HO CHI MINH

- 7. THE ROAD TO DIEN BIEN PHU

- 8. GARRISON STATE

- 9. “ROAD TO SOCIALISM”

- Part Three: INSURGENCY IN THE SOUTH

- 10. THE LOST DECADE

- 11. AGONY OF A WAR

- 12. NGO DINH DIEM—MAN AND MYTH

- 13. A TALE OF TWO REPUBLICS

- 14. THE ECONOMIC BASE

- 15. THE SECOND INDOCHINA WAR

- 16. “NATIONAL LIBERATION”

- 17. THE TWO VIET-NAMS IN PERSPECTIVE

- The North

- APPENDIXES

- II. MANIFESTO OF THE EIGHTEEN

- III. PROGRAM OF THE NATIONAL LIBERATION FRONT OF SOUTH VIET-NAM

- IV. PROCLAMATIONS BY SOUTH VIETNAMESE COUNCIL OF GENERALS

- V. DECISION OF THE REVOLUTIONARY COUNCIL

- VI. PROCLAMATION BY GENERAL NGUYÊN KHANH

- VII NGUYÊN CAO KY CONVENTION

- VIII. DECLARATION OF MANILA

- NOTES

- BIBLIOGRAPHY

- INDEX