eBook - ePub

The Politics Of Mineral Resource Development In Antarctica

Alternative Regimes For The Future

William E Westermeyer

This is a test

- 268 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Politics Of Mineral Resource Development In Antarctica

Alternative Regimes For The Future

William E Westermeyer

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Originally published in 1984. Antarctica can no longer be considered merely a highly specialized area of interest to a relative handful of explorers and scientists. World political leaders who, in an era of resource politics, are looking to potential sources of supplies of living and non-living resources. Antarctica may prove to be a source of such supplies. In this volume, Dr. Westermeyer's study of the options available for a mineral regime and probable costs comes at an opportune time, helping participants understand the issues and find acceptable solutions.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Politics Of Mineral Resource Development In Antarctica by William E Westermeyer in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction

Sovereign claims to most land areas of the world have long been internationally recognized. More recently jurisdictional claims have been extended to the coastal waters of the world's oceans. The movement to enclose still more ocean space is now well established. However, sovereign jurisdiction over sev-several important areas of the world --notably the deep seabeds and Antarctica--has still not been firmly established. Competition for access to raw materials is increasing, and the rapid pace of technological innovation is enabling highly industrialized countries to expand the frontiers of their economic activities to these once inaccessible areas. Willy Ostreng and Gunnar Skagestad refer to the problems to be faced in these still largely unexplored and inhospitable areas as "the challenge of new territories." "It is a fairly safe bet," they write, "that development [in these areas] is going to accelerate, in intensity as well as in extent, in the years to come, as the impact of the global raw material scarcity makes itself felt. This makes for a new development in international politics, a development to which the world community will have to adapt and accomodate itself." "How will this adaptation process manifest itself," they ask, "--through conflict or through cooperation?"1

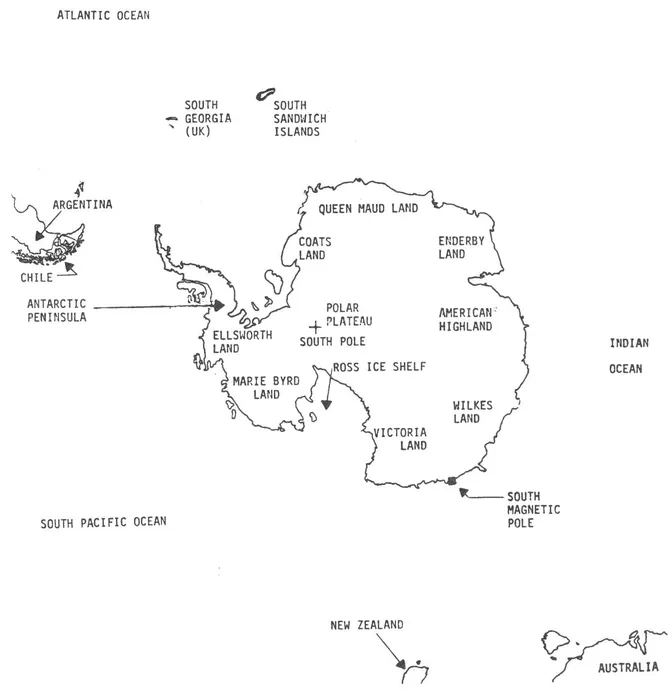

This study focuses on one of the "new territories"-Antarctica. Since the 1957-1958 International Geophysical Year Antarctica has been the almost exclusive preserve of scientists who study meteorology, upper atmosphere physics, solid earth geophysics, geology, biology, and human physiology. Increasing interest in Antarctica on the part of non-sc1entists

Figure 1-1. Antarctica

centers around the growing evidence that resources exist there which might be economically exploitable in the forseeable future. In the case of the living, renewable resources of the Southern Ocean, such as krill2 and fin fish, harvesting has already commenced. The non-living resources of Antarctica have not yet begun to be exploited, yet indirect evidence suggests there could be several dozen major mineral deposits in ice-free areas. Most significantly, oil and natural gas are likely to exist under the continental shelves of Antarctica. As the world price for fossil fuels increases, commercial exploitation of Antarctic energy resources becomes more feasible. Thus, Antarctica, like other areas of the world before it, has become the object of activities which create the need for regulation and control.

Those countries active in Antarctica have been paying close attention to this topic. Discussion of the non-living resources of Antarctica dominated the Eleventh Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meeting held in Buenos Aires in June, 1981. After intensive negotiations, the representatives agreed upon a recommendation (XI-1, see appendix B) on this subject which called for consultative state governments to conclude a regime for Antarctic mineral resources without delay. Since this meeting, two special meetings to consider the formulation of an Antarctic minerals regime have been held in Wellington, New Zealand. The most recent of these occurred in January 1983. It is evident that the will to devise an acceptable regime is present, but little progress on the most difficult issues has been made yet. Agreements concerning veto powers of consultative states and internal accommodations among those with incommensurable juridical positions will not easily or soon be reached.

Seven territorial claims have been made in Antarctica, but none of the claims is widely recognized. In 1959 the seven claimant states (Argentina, Chile, New Zealand, Australia, Norway, France, and the United Kingdom) and five other states with interests in Antarctica (the United States, the Soviet Union, Japan, Belgium, and South Africa) negotiated the Antarctic Treaty.3 The Treaty has frequently been cited as a model of international cooperation.4 For the last twenty years these twelve original consultative states and two others which have been granted consultative status (the Federal Republic of Germany and Poland) have cooperated in the management of the Antarctic.5

It is by no means certain that this cooperation will continue. The stakes are much higher now than they were when the Antarctic Treaty was negotiated. While Antarctica has remained open to all for the conduct of scientific research, free of nuclear waste, demilitarized, and, for the most part, a pristine environment, it would be an overstatement to speak unreservedly of the vision of the Treaty negotiators. The Treaty is less than an ideal document. It has served more to legitimize the status quo existing prior to 1959 than as a device for breaking new ground. Treaty countries did not try to resolve the sovereignty dispute. Claimant countries were not required to renounce their claims, nor were non-claimant countries required to recognize claims that had been made.

To date there have been few problems or controversies which the consultative states have not been able to resolve at their biennial meetings. A major success has been the recent negotiation and ratification of a convention governing the exploitation of Antarctic marine living resources.6 Cooperation has been relatively easy since bargaining has been restricted to these few parties, goals have not been strongly in conflict, and resource scarcity has not been a divisive issue. However, the Antarctic Treaty does not address the exploitation of non-living resources. Now that exploitation of these resources can be foreseen, the potential for conflict looms large. Tension among some signatories of the Antarctic Treaty has dramatically increased recently. The conflict between Argentina and the United Kingdom in the Falkland (Malvinas) Islands will likely have an effect on the resolution of problems in Antarctica. The ingredients of this conf1ict--jurisdictional ambiguity, potentially valuable resources, and national pride--are present in Antarctica as well. The negotiation of a regime within which resource development can proceed has become a more pressing issue. In the following chapters some of the alternatives for a comprehensive regime for Antarctica will be closely examined and evaluated.

Several significant policy questions need to be addressed well before the actual exploitation of nonliving resources begins. For one, who will benefit from the exploitation of the resources of Antarctica, and who will bear the costs? Claims to Antarctica have in part been prompted by the expectation of gain from the exploitation of resources, though it is not immediately clear whether claimants would gain more by pursuing their claims to sectors of Antarctica or by sharing Antarctica with other consultative states and thereby gaining access to a portion of the resources of the entire continent. Non-claimant Treaty states desire non-discriminatory access to the resources of Antarctica. Both groups would prefer to limit access and the distribution of gain to those states which have been historically active in Antarctica, but they recognize that the international community that is not party to the Treaty believes it has some stake in the resources of Antarctica as well. These non-Treaty states would prefer a resource regime in which all share in some way the wealth of Antarctica. But how they would share is an open question. What is an equitable distribution of resource, and how can an equitable distribution be realized? Moreover, can a can a system which requires consensus on all important matters (as does the present Antarctic Treaty) succeed as part of a comprehensive resource management regime?

In addition to questions of participation in development, there are questions of conflict among development objectives and between development and environmental considerations. All of these conflicts are first order issues that must be settled. What are the tradeoffs between economic goals and various noneconomic goals, and what are the probable consequences of different patterns of resource exploitation for such non-economic values as the conservation of living species and the preservation of the environment? Antarctica is an arena where not all actors have the same value structure. There are potential conflicts among the development of energy resources, the exploitation of food resources, preservation of the environment, and continuance of the spirit of cooperation that has been a hallmark of the Antarctic Treaty for twenty-one years. Hydrocarbon exploitation is bound to produce negative effects in the form of both environmental degradation and multiple-use problems. Unilateral action to develop resources would probably bring an end to the cooperative era that has thus far characterized Antarctic decision making. How important is the development of mineral resources in view of these and other values which Treaty states profess to hold? The manner in which territorial disputes are eventually handled will, ipso facto, affect not only these first order issues, but second order issues involving specific institutional arrangements and regulatory requirements as well. Whatever the regime type, a set of decision makers will have to worry about such second order questions as: What regulatory requirements will be necessary for protection of the environment in the advent of resource exploitation? What institutional arrangements are most likely to facilitate an efficient pattern of resource exploitation? How will new entrants be treated if resources are initially allocated only among the members of a select group? What prerequisites must entities seeking to mine or drill the resources in Antarctica satisfy? And what would constitute an evaluation scheme for assessing the effectiveness of regulations? When the first order problems are resolved, answers to these questions will be easier to formulate.

A management regime for the development of the mineral resource potential of Antarctica will, of necessity, spell out who has management jurisdiction over resources. A regime might be designed which skirts the territorial Issue, but this will be a more difficult task than It was when consultative states negotiated the living resources convention. One way in which to focus thinking about developing a nonliving resources regime for Antarctica is to identify discrete alternatives and to evaluate these alternatives in terms of a common set of criteria. The alternatives for a mineral resource regime for Antarctica include accepting existing but non-perfected territorial claims, granting unrestricted access to anyone capable of operating in Antarctica, and internationalizing Antarctica as part of the "common heritage of mankind." These options set the bounds within which compromise solutions are likely to be found among competing national interests in Antarctica. Possible compromises include treating the resources of Antarctica as shared property but otherwise recognizing the special status of claimants, declaring a condominium for Antarctica which would be governed by user states, or governing Antarctica as a United Nations trust territory with countries active there serving as joint trustees.

States have already begun to develop preferences for one or another type of minerals regime; however, to date no systematic study of competing alternatives has been attempted. The systematic evaluation of such a complex issue requires use of an appropriate study technique. Multi-Attribute Utility analysis (MAU) will be employed in this study. MAU was developed by decision analysts as an aid to making better decisions. In making most complex decisions, decision-makers must consider multiple, often competing objectives, and the relative importance of these objectives must be weighed. The option which can perfectly satisfy all competing objectives rarely exists, but MAU provides a rational method for choosing the best alternative from among specified options. Using MAU it will be possible to estimate which of the regimes under consideration here provide the most utility (that is, provide the greatest payoff) for states active in Antarctica. Moreover, by using Multi-Attribute Utility analysis, a conscious effort is being made to structure evaluation of this issue in more comprehensive, though novel way. MAU forces one to think systematically about components of the issue that may easily be overlooked using other techniques. Fresh insight may thus result, making possible a more accurate estimate of preferences for alternative forms of Antarctic mineral management regimes.

The best regime for the United States, for example, would be that regime which maximizes satisfaction of U.S. interests. Each of the twelve alternatives which will be considered can be evaluated (using MAU) by estimating the degree to which each of the interests of the U.S. is satisfied by each option. Some of these interests are more important than others. Therefore, if the relative importance of interests can be determined, this added information can aid in the selection of options. Since the best U.S. alternative is unlikely to be the best alternative for other countries active in Antarctica, we can gain insight into what a compromise regime might look like by evaluating the same set of options for each consultative country. While a common set of interests may be defined for analytical purposes, each country will likely attach different importance to each interest than the U.S. does. If this were not the case, there would be little difficulty negotiating a widely acceptable, comprehensive minerals regime.

Data concerning the relative importance of the interests of the U.S. and other consultative states is not widely available. In order to generate this data a questionnaire was sent to Antarctic experts in each consultative country. The importance weights determined with the aid of this questionnaire represent the best available non-official estimates of the relative importance of each consultative country's interests. This data has been combined with estimates of the extent to which each alternative satisfies each objective in order to derive each country's utility for each regime. Many assumptions were made in estimating the future impact of alternatives on satisfaction of interests. If these assumptions are plausible, and if estimated interest weights are not too far off the mark, the aggregate utility scores derived from this data should accurately reflect the relative importance of each regime for each country.

The use of MAU suggests the content and order of the following chapters. The current regime and possible alternatives are introduced before a chapter describing research methods because they can stand alone. Having introduced the problem and possible solutions, the methodology chapter describes how these alternatives will be evaluated. The final chapters carry out this evaluation and present findings and conclusions. Specifically, chapter two of this study is a review of resource allocation problems in Antarctica. It examines in some detail the success and shortcomings of the present regime. The cornerstone of this regime is the Antarctic Treaty, but other significant elements include recommendations of the Consultative States adopted at biennial meetings, the Convention on the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources, and the International Convention for the Regulation of Whaling. In the last half of the chapter the non-living resource potential of Antarctica and the possible environmental consequences of resource development are examined.

Chapter three introduces alternative regimes for Antarctica. The regimes selected for examination represent the entire range of options from those that are most inclusive (e.g., a regime modeled after the provisions of the proposed Internation...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- LIST OF TABLES AND FIGURES

- ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- FOREWORD

- 1. INTRODUCTION

- 2. A REVIEW OF RESOURCE ALLOCATION PROBLEMS IN ANTARCTICA

- 3. ALTERNATIVE REGIMES FOR ANTARCTICA

- 4. THE USE OF MULTI-ATTRIBUTE UTILITY ANALYSIS FOR DETERMINING REGIME UTILITIES

- 5. ANALYSIS PART I: THF COMPONENTS

- 6. ANALYSIS PART II: FINDINGS

- BIBLIOGRAPHY

- APPENDIXES

- INDEX