eBook - ePub

Social Democracy in Capitalist Society (Routledge Revivals)

Working-Class Politics in Britain and Sweden

This is a test

- 184 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Social Democracy in Capitalist Society (Routledge Revivals)

Working-Class Politics in Britain and Sweden

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

First published in 1977. This book considers the nature of industrial society, contemporary capitalism and the impact of political ideas on social structure. These ideas are discussed by reference to the impact of social democracy on the structure of capitalist society in a comparative analysis of Britain and Sweden — including an interview survey of industrial workers socio-political attitudes. The study is concluded by a general discussion of the role of social democracy in capitalist society. It is argued that the development of social democracy generates 'strains' which, in the long term, question the legitimacy of capitalism among industrial manual workers.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Social Democracy in Capitalist Society (Routledge Revivals) by Richard Scase in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business generale. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

1 | THE SOCIAL STRUCTURES OF BRITAIN AND SWEDEN: ‘AN OVERVIEW’ |

Two social structures as complex as those of Britain and Sweden create problems for any comparative analysis. In order to provide a background to the study of class inequalities in the two countries, it is difficult to decide which factors to include; sociologists are unlikely to agree about the criteria and any selection of issues will almost certainly incorporate personal prejudices and interests. Therefore, the present analysis will only consider developments which the investigator feels to be the most important for the study of their contemporary class structures. In this, more attention will be devoted to Sweden on the grounds that information for that country is generally less known than the material for Britain; for the latter, references will be given to the relevant discussions.

To investigate aspects of class inequality in the two countries it is necessary to describe historical developments in terms of (i) patterns of industrialisation — together with the related processes of urbanisation — and (ii) patterns of political change. For a more comprehensive analysis it would be necessary to consider other factors. But this study only focuses upon industrialisation and political change, since these are considered by many to be among the more important determinants of class inequalities.1

(i) Patterns of industrialisation

Sweden was predominantly an agricultural country until the early part of the twentieth-century. The first reliable statistics for the occupational structure describe the situation in the late eighteenth century. These were collected by the clergy and have been interpreted by Heckscher. According to these, 5 per cent of the Swedish population in 1760 consisted of the nobility, the clergy and other ‘gentlefolk’, 10 per cent of soldiers and state employees, 6 per cent of traders, craftsmen and merchants and 79 per cent of rural craftsmen, cottagers, crofters and farmers.2 There were few signs, therefore, to suggest that Sweden in the latter part of the eighteenth century was at the beginning of any ‘take-off’ in industrialisation – a process which, in fact, was not to occur until a century later. But there was some commerce at this time; copper and iron ore were exported while burghers were allowed to manufacture and trade goods within terms stipulated by the state. However, despite the fact that some of these became extremely wealthy, their impact on the social structure was very limited, if only because of the predominantly agrarian economy. But like their counterparts elsewhere, the capital which they accumulated was to play a significant role in the later industrialisation of the country.3

It is difficult to compare the social structure of Sweden with that of Britain in the middle of the eighteenth century because of the absence of comparable statistical evidence. The only material which can be used for the purposes of comparison is Joseph Massie’s estimate of the social structure in 1760. Massie’s figures have been analysed by Mathias and these suggest that the social structure of Britain was much less agrarian than that of Sweden.4 They indicate that a higher proportion of the population in Britain was engaged in trading and manufacturing; perhaps something like 40 per cent compared with much less than 10 per cent in Sweden. But despite this, there were a number of common features in the social structures of the two countries. Both were agrarian economies and it seems very likely that the life chances and life-styles of the greater majority of the two populations were similar; in the rural areas most of the agrarian populations existed at subsistence levels with poor diets. Mortality rates were high and there were periodic outbreaks of famine. Samuelsson claims that in Sweden, only hunting and fishing supplemented a drab diet which for the agrarian population consisted mainly of bread.5 Conditions for the English rural population were probably not much better and whether or not early industrialisation raised living standards for this sector of society has been the subject of dispute among economic historians.6

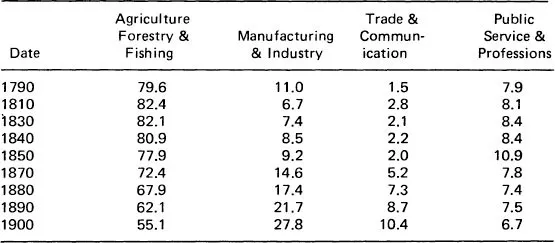

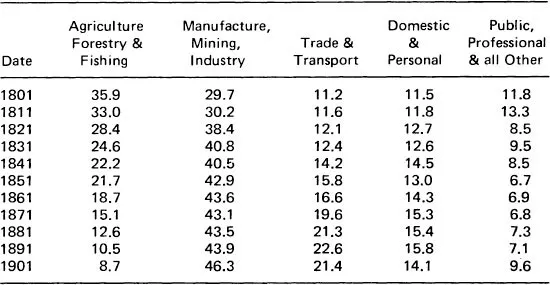

However, from the end of the eighteenth century until the beginning of the twentieth, the social structures of the two countries were characterised by distinctive differences. While Britain rapidly industrialised throughout the nineteenth century, Sweden remained an almost completely agrarian society. Differences in the development of the two social structures during this period are illustrated in Tables 1.1 and 1.2.

It is clear from Tables 1.1 and 1.2 that Sweden in 1900 was less industrialised than Britain in 1801. Whereas the period of most rapid industrialisation in Britain was before 1831, the comparable era in Sweden was after 1880. But this is not the only difference; there were also variations in the processes whereby industrialisation occurred. While it led to rapid large-scale urbanisation in Britain, this did not happen to the same extent in Sweden. Instead, industrialisation tended to be much more dispersed, mainly because of the key importance of iron mining and forestry in Swedish economic growth. Iron ore had been exported from as early as the thirteenth century and by the eighteenth century Sweden dominated the world market.9 It was the mining of ore which led to one of the principal features of early industrialisation in Sweden — the ‘bruks’. These were essentially mining villages which had developed within the context of the rural economy. They were usually controlled by a single family, who owned the mines, the land and the employees’ houses. They were structured in a very hierarchical manner, so that social relationships between employer and employee were often paternalistic, with the owners providing not only employment but also rudimentary forms of ‘social welfare’ such as care of the sick, the old and the widowed. ‘Bruks’ were significant for the early industrialisation of Sweden because they avoided many of the social conflicts found in the few densely populated urban areas. The origins of organised labour, therefore, are not to be found in the ‘bruks’ but among the craftsmen of Stockholm, who had often obtained their training abroad and gained first-hand experience of industrialisation in other countries.10

Table 1.1: The percentage distribution of the total Swedish population according to main industrial groups, 1790–19007

Source: Extracted from A-L. Kalvesten, The Social Structure of Sweden, Stockholm, 1966, Table 4.

Table 1.2: Estimated percentage distribution of the British labour force, 1801–19018

Source: Extracted from P. Deane and W. Cole, British Economic Growth 1688–1959 (2nd ed.), Cambridge, 1967, Table 30.

During the nineteenth century the signficance of the ‘bruks’ declined because of growing international competition; this was mainly because competitors started to use coal instead of charcoal in the production of iron. Consequently, there was a concentration of output in the Swedish industry so that while a few of the ‘bruks’ developed into steel towns, most of them either stagnated or ceased production. Nevertheless, the iron industry, in a more ‘rationalised’ form, continued to be one of the major bases of Swedish industrialisation; during the 1870s it led to the growth of the machine and shipbuilding industries, while in the 1890s its products were used for the manufacture of electrical goods. It was these developments which, in the earlier years of the twentieth century, contributed to the expansion of such urban areas as Stockholm, Gothenburg and Malmö. At the same time, the rapid exploitation of iron ore in the north of Sweden generated the growth of such urban settlements as Kiruna and Lulea.11

In addition to the production of iron and the manufacture of its various products, the other major factor in Swedish industrialisation was the exploitation of forests, a process which had two major consequences. First, there was the growth of saw-mill communities on rivers in northern Sweden. Secondly, the development of forest-based industries led to the growth of small carpentry workshops which specialised...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Original Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Introduction: The Comparative Study of Societies

- 1. The Social Structures of Britain and Sweden: ‘An Overview’

- 2. Class Inequality in Britain and Sweden

- 3. The Social Survey: A Study of Attitudes Among Two Samples of Workers

- 4. Conceptions of the Class Structure: (1) Inequalities of Opportunity

- 5. Conceptions of the Class Structure: (2) Inequalities of Economic Condition

- 6. Conceptions of the Class Structure: (3) Inequalities of Power

- 7. Conclusions

- References

- Index