eBook - ePub

Incomes Policies, Inflation and Relative Pay

This is a test

- 294 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Incomes Policies, Inflation and Relative Pay

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This book, originally published in 1981, is a major reassessment of the strengths and weaknesses of incomes policies. A distinguished group of economists comprehensively review the rationale and history of the field, giving special attention to the role fo the public sector, the question of low pay and the differing approaches to incomes policies which have been adopted in Europe and North America.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Incomes Policies, Inflation and Relative Pay by Les Fallick, R F Elliott, Les Fallick, R F Elliott in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Economics & Economic Theory. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Chapter 1

Incomes Policies: Some Rationales

Introduction

There already exist a number of surveys of incomes policies – for a recent UK survey, see Blackaby (1978) – and there seems little point in adding to the list. Rather, the primary purpose of this chapter is to locate the underlying rationale for incomes policies in an analytical-cum-historical perspective. Thus, a series of rationales is suggested, each of which describes, in part at least, the views of identifiable groups of economists at certain points in time.

The emphasis is on rationales suggested by economic analysis. This implies some restriction on the scope of the treatment in so far as it excludes a detailed account of the political calculus leading to the adoption and termination of incomes policies.1 This chapter is restricted in another way also; it is mainly concerned with the case in favour of incomes policies and does not attempt to present a full cost-benefit analysis of such policies.

Naturally enough, views among economists about the role for, and rationale of, incomes policies have evolved in conjunction with views about the determination of wages in a market environment, so that in the period with which we are concerned (from the earliest post-Second World War years to the present) there have been oscillations connected with the rise and fall of the Phillips curve, the expectations-augmented Phillips curve, and the real wage resistance views of money wage determination.

The natural starting-point is, however, with the legacy of the Keynesian revolution in macroeconomic thinking, which it is convenient to label, borrowing a phrase from Hicks (1974), the ‘wage theorem’ view.

1. The wage theorem view

The macroeconomic habit of analysis promoted by the Keynesian revolution, and instilled by Keynes himself, involves, as Hicks (1974) has pointed out, the ‘wage theorem’. Everything in the General Theory is done in terms of variables measured in ‘wage units’ which, it seems clear, Keynes intended to be taken, most of the time, as the same thing as working in ‘real terms’.2 As the determination of the money wage itself is omitted from the model, the implication of an orthogonality between money wage determination and the economy described by the model seems clear. This is obscured by the habit adopted by Keynesian expositors of working in terms of fixed wages and prices which elides the rather awkward implication of the ‘wage theorem’ that a rise in money wages is accompanied by an equal proportionate rise in prices and in the money supply, and leads (as described by Hicks) to the misleading impression that the economy recognises only two states: one of less than full employment in which money wages do not rise, and another of full employment in which they do. To complete the Keynesian view, it then seems that one (perhaps both) of two routes can be pursued. First, if wage determination is orthogonal to the economy, it must be determined ‘somewhere else’ and the task is to describe this. This leads directly to the view that the determination of money wages is a political question. The second alternative is to recognise that the sharp dichotomy between ‘under-full’ and ‘full’ employment is too sharp: this route leads to the Phillips curve.

The former view is identified here as the ‘wage theorem’-related case for incomes policy. How close it is to what Keynes would have said is impossible to know; but it is now clear that Keynes was well aware of the problem posed by the ‘wage-raising’ powers of trade unions, and in replying to a comment he received whilst acting as Editor of the Economic Journal on a paper of his own, Keynes characterized the issue as ‘a political rather than an economic problem’ (Keynes, 1980, p. 38). It was, however, a view elaborated upon by Keynesian economists such as Kalecki (1944), Robinson (1937) and Worswick (1944). The argument is that the maintenance of full employment removes the restraint upon trade unions to press for higher wages, that there is a limit to the degree of inflationless redistribution towards labour which can accommodate these increases, and that inter-union rivalry makes it impossible for the lesson that higher wages means higher prices to be learnt; rather, it encourages an inflationary spiral. Individual (group) money wage rates depend heavily on relativities, with the result that the absolute (average) level of money wages (and prices) is essentially indeterminate, for the maintenance of full employment will require monetary accommodation of the money wage-price outcome. The result is that a wage policy is required; and that its successful formulation requires a degree of centralisation of union bargaining. ‘Wage bargaining in full employment is, in fact, a political problem, and will be settled on the political plane’ (Worswick, 1944).

The starting-point of this approach is very clear. As full employment is to be guaranteed, a discipline of money wage increases by way of reduced employment is not available.3 Clearly, such a view would be undermined, if it could be shown that the necessary discipline could be enforced at only a marginal sacrifice of full employment. To stand by the ‘wage theorem’ case for incomes policy if this were true would seem to be sheer stubbornness. In fact, of course, the view denies that a marginal sacrifice of output and employment is all that is required for the maintenance of an acceptable rate of inflation, and suggests – to employ Phillips curve language – that not only is the slope of the Phillips curve shallow, but that it is also unstable.4

The earliest formulations of the ‘wage problem’, and the associated rationale for an incomes policy seem in essence to capture most of the significant elements in subsequent debate. In particular, they point to the significance of the issue of relativities, the significance of the stability and the slope of the short-run Phillips curve, and so on. And, whilst they do not employ the conceptual elaborations afforded by later theoretical and applied work, these formulations stand up well to subsequent experience. We shall therefore return to an elaboration of this view in the concluding section of the paper.

2 The Phillips curve

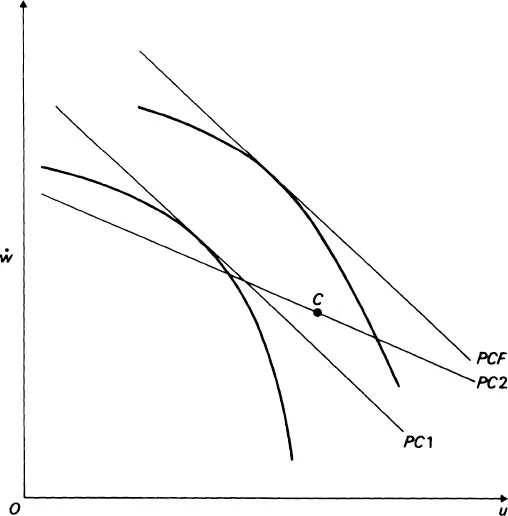

The ‘discovery’5 of the Phillips curve (Phillips, 1958) was, it seemed at the time (and for some while after) a severe blow to the wage theorem view. It suggested that there was a relationship between the rate of wage change and the level of unemployment, and early versions of the relationship stressed the relative steepness of the curve. Although closer inspection revealed that the stability of the Phillips curve was far from guaranteed, and Phillips’s fitting procedure was criticised,6 the construct was accepted with considerable enthusiasm by the economics profession and empirically replicated by economists for other countries and times. One reason for its ready acceptance is no doubt that it seemed to fill in a missing box in the Keynesian system: it endogenised the money wage to the economy modelled by the system, an intellectually more satisfying achievement (and more appealing to the intellectual imperialism of economics!) than the orthogonality implicit in the wage theorem. Perhaps for this reason Johnson described the Phillips curve as ‘the only significant contribution to emerge from post-Keynesian theorizing’ (Johnson, 1970). A stable, steeply sloped Phillips curve dispenses with the premium on incomes policy; for it leaves open the use of demand management policy to achieve an acceptable trade-off of inflation and unemployment. Thus Paish (1962) argued that demand management policies could bring about an acceptable level of inflation with unemployment at 2¼ per cent or more.7 Nevertheless, incomes policies were widely pursued in practice and their success diagnosed by reference to the Phillips curve. Thus, an incomes policy could be viewed as shifting the intercept term and/or the slope of the Phillips curve and its efficacy accordingly estimated by measuring the size and significance of such shifts. One of the better-known investigations of this type is that by Lipsey and Parkin (1970). Their results led them to suggest that the effect of incomes policy was to shift and swivel the Phillips curve in such a manner as, historically, to have achieved a kind of optimum-pessimum result. The argument is illustrated in Figure 1.1. In that figure, PC1 is the Phillips curve without incomes policy and PC2 the curve with incomes policy imposed. The incomes policy effect clearly allows for ‘social welfare’ improvement, as indicated by the preference schedules (drawn concave to the origin, since both inflation and unemployment are ‘bads’). However, Lipsey and Parkin indicated that the authorities had actually chosen a position like C on PC2, clearly a grievous error. Whilst the analysis suggested by the investigation was interesting, it was nevertheless flawed in two respects: first, the data scatter was too concentrated to support the projections suggested. Secondly, and more fundamental (being a criticism of a large number of other studies of incomes policies effects), the test for the effectiveness of incomes policies involves the counterfactual ‘what would inflation have been (given employment) had no incomes policy been in operation?’ The use of the Phillips curve to supply the answer to the counterfactual implies that the period in question, in all respects except the imposition of the incomes policy, was homogeneous with the sample from which the Phillips curve was estimated. However, it is possible, if not indeed probable, that the adoption of the incomes policy was itself prompted by reasoning that the inflation experience of the period would not have been a random drawing from the sample, but would, rather, have been significantly worse. If so, the appropriate counterfactual is represented by some other schedule – perhaps like PCF in Figure 1.1 – which would have been unambiguously worse then PC2.8

Figure 1.1 The Lipsey–Parkin analysis of incomes policy

If the relative goodness of fit and steep slope of the ‘early’ Phillips curve counted against the ‘wage theorem’ view, the discovery in the late 1960s and 1970s of considerable instability in the Phillips curve, though leading to a revival of the wage theorem view and a renewed interest in incomes policy, also had another outcome – the augmented Phillips curve.

3 The augmented Phillips curve

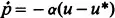

If the empirical basis of support for the augmented Phillips curve lay in the clear evidence that the ordinary (unaugmented) Phillips curve was a poor predictor of inflation in circumstances of ‘stagflation’, its theoretical basis was the seemingly simple but radical suggestion that the only support for the trade-off suggested by the Phillips curve was that of money illusion. If, on the other hand, it was recognised that the position of the short-run Phillips curve depended on inflation expectations it could be seen that this trade-off would disappear. Thus the suggestion is to ‘augment’ the ordinary Phillips curve,

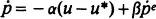

where u and u* are respectively the actual and non-inflationary rates of unemployment and ṗ the rate of inflation, by a term in inflation expectations (ṗe) as:

Setting u = u* and ṗ = ṗe here gives a long-run solution of ṗ = o in either case, provided β < 1. On the other hand, if money illusion is completely absent (β = 1), the equilibrium solution for ṗ is indeterminate. In this case, u* must be renamed the ‘natural rate of unemployment’, a rate which is compatible with any steady rate of inflation.

The augmented Phillips curve provides a less attractive unemployment-inflation trade-off in the long run than the unaugmented curve –

rather than −α−1, and zero in the case where ‘money illusion’ is completely absent (that is, where β = 1). A steeper trade-off, on previous argument, would make the case for inc...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- LIST OF TABLES AND FIGURES

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- INTRODUCTION

- 1 INCOMES POLICIES: SOME RATIONALES

- 2 INCOMES POLICY AND AGGREGATE PAY

- 3 PUBLIC AND PRIVATE SECTOR PAY AND THE ECONOMY

- 4 INCOMES POLICY AND THE PRIVATE SECTOR

- 5 INCOMES POLICY AND THE PUBLIC SECTOR

- 6 INCOMES POLICIES AND LOW PAY

- 7 THE AMERICAN EXPERIENCE WITH INCOMES POLICIES

- 8 INCOMES POLICY: THE RECENT EUROPEAN EXPERIENCE

- 9 INCOMES POLICIES, INFLATION AND RELATIVE PAY: AN OVERVIEW

- APPENDIX: INCOMES POLICIES: A SHORT HISTORY

- INDEX