![]()

Part 1

Overview

Stress and affluent sustainable consumption

![]()

1

Introduction

The sustainability of affluent consumption

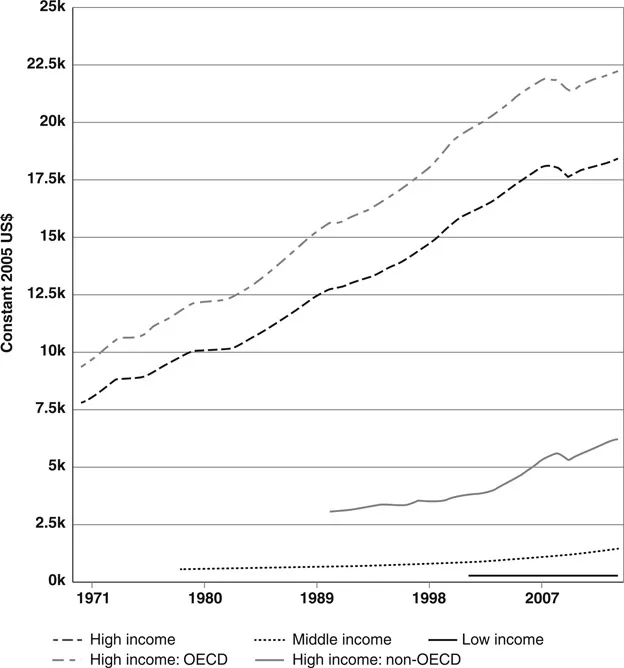

This book addresses affluent sustainable consumption from an embodied perspective. It focuses on the increasing levels of affluent consumption that follow increases in current household income and which pose a serious threat to the achievement of an environmentally sustainable system of consumption and production (Alfredsson, 2004; Baxter and Jermann, 1999; Brännlund et al., 2007; Carlsson-Kanyama et al., 2005; Lusardi, 1996; Hurth, 2010; Lenzen et al., 2006; Tukker et al., 2010). All consumption activities have not only an impact on the environment through resource and energy use, but also threaten planetary boundaries (Rock-ström et al., 2009). The concept of planetary boundaries suggests nine earth system related to global production and consumption processes – climate change; biodiversity loss, the nitrogen cycle, the phosphorus cycle, stratospheric ozone depletion, ocean acidification, global freshwater use, land use change, atmospheric aerosol loading and chemical pollution – that potentially risks being disrupted (Biermann et al., 2012; Rockström et al., 2009). The concept of tipping points is used to denote the threshold value that should not be passed if we want to avoid disruptive earth systems. Rockström et al. (2009) estimate that the threshold values of three earth boundary conditions highly connected to global provisioning and exchange systems – climate change, biodiversity loss and the nitrogen cycle – have already been surpassed. Thus, in a resource-constrained world, in which consumption levels need to be increased for reasons of poverty and equality in developing economies, it is urgent to reduce the level of consumption by the affluent (Cohen et al., 2010). World Bank statistics presented in Figure 1.1 show that (1) high income households increase their consumption expenditures at a higher rate than lower income households over time and (2) OECD high income households increase their consumption faster than non-OECD high income households.

Figure 1.1 Household expenditure per capita in relationship to income, 1971–2007

Defining affluent consumption

Affluent consumers carry a disproportionate share of the environmental impact of market exchanges, as illustrated by the planetary boundary concept. Therefore, it is important to define affluent consumption as well as the environmental impact that follows from it. By doing so, we can differentiate between affluent consumption and consumption “experienced by the people of poverty and adequacy” (Sheehan, 2010). Affluent consumption is characteristic of Western economies, but growing numbers of affluent consumers are found in developing economies such as China and India, their numbers rising as incomes increase.

Affluent consumption is enabled by financial resources, which are accessed by systems of credit to varying degrees (Cohen, 2007; Ransome, 2005). In this book, affluent consumption is defined in relative terms rather than as a set of fixed resources or in terms of the ownership of specific goods. The relative definition of Western affluent consumption is based on two intertwined dimensions: access to resources for consumption purposes and consumption objects as symbols for social desirability. These two dimensions of affluent consumption are interdependent, as surplus income is needed to consume beyond basic needs. Access to surplus income creates the capacity to freely spend and choose which products and services to consume, as well as the expectation of being able to do so (Ransome, 2005). In accordance with the affluence hypothesis, the consumer cultures of the industrialized West, and our identities, feelings and way of living, are to a large degree shaped by consumption (Arnould and Thompson, 2005; Campbell, 1987; Ransome, 2005). Readily accessible surplus income means that affluent consumers not only can choose what to consume, but also can consume products and services for reasons of “pleasure and satisfaction in and of themselves without always being tied to satisfaction of basic needs” (Ransome, 2005, p. 5).

One consequence of the affluence hypothesis is that the predominant driver for affluent spending is the desire to acquire novel and socially desirable products and services. Novelty is a generic quality in so called fashion-driven industries in which products are subject to frequent updates in style and design. Marketing and advertising practices, where new products are linked to idealized identities, heavily support “the social pressure” (keeping up with the Outer and Inner Joneses) to acquire products and services in fashion (Cohen, 2007; Moisander et al., 2010). Automobiles, clothing, furniture, electronics, home furnishing, household apparel, mobile phones, clothing and holiday destinations are examples of products that are continuously subject to change, obsolescence or replacement, and are forcefully advertised as an essential part of happy and successful lives (Desmeules, 2002; Moisander et al., 2010). The fashionable character of products and services resides not in their inherent functional qualities but in their social value (Banister and Hogg, 2004; Bourdieu, 1984; Rafferty, 2011; Schiermer, 2011; Simmel, 1904; Thompson and Haytko, 1997). They are consumed to a substantial extent because they feature novel characteristics that are valued by others, although their functionalities often partially reside in the pre-existing object (Alvesson, 2013). As novel products are socially desired and highly valued in Western consumer cultures, refraining from consuming these can be problematic for individual consumers. Research shows that fashion consumption is motivated by insecurity alleviation and mood restoration (Burroughs and Rindfleisch, 2002; Clarke and Miller, 2002; Dittmar, 2008; Mick and Demoss, 1990; Moschis, 2007; Pavia and Mason, 2004; Woodruffe-Burton and Elliott, 2005). Thus, it seems that affluent consumers continuously engaged in increasing consumption – which is unsustainable – do so not to feel good about themselves or to enjoy life but rather to avoid feeling bad about not having the latest products or visited the newest exotic holiday destination.

In this book, affluent consumption in the Western consumer culture context is defined as the financial possibility to consume in accordance with socially desirable consumption (fashion) trends. This does not mean that all affluent consumers “overconsume”, i.e. engage in consumption of goods and services just for the sake of socially desirable novelty. Instead, this definition of affluent consumption acknowledges that such consumption comes in various shades depending on financial resources as well as interest and engagement in the marketplace.

Affluence and unsustainable consumption

One way to show the environmental impact of affluent consumption (in relation to the earth’s capacity to provide resources needed without exceeding planetary boundaries) is to use ecological footprint analysis (Cohen, 2007; Wackernagel et al., 1999). The ecological footprint is a tool that estimates the productive land needed to uphold and sustain resources for consumption and waste assimilation of a specific population (Wackernagel et al., 1999). The concept of the earth’s carrying capacity, or biocapacity, is used to illustrate “human demand on the environment into the area required for the production of food and other goods, together with the absorption of wastes” (Wackernagel et al., 2002, p. 9266). The biocapacity depends on land type and the productive capacity of the land (Global Footprint Network, 2016). If we assume generational equality and solidarity, and if we desire to live within the capacity of our planet, the current biocapacity per person is 1.7 global hectares (Global Footprint Network, 2016). In other words, we have 1.7 hectares each at our disposal to assure that our needs are met. If our way of living requires more than 1.7 hectares, someone else’s ability to live within the earth’s carrying capacity and planetary boundaries is at risk. For example, if a nation’s ecological footprint per capita is 6.8 hectares, the citizens’ way of living in this country requires almost four times the resources and wastes that our planet can reproduce and absorb.

Current ecological footprint data show that all affluent Western economies, as well as a large group of developing economies, demand many more resources and waste than can be regenerated and absorbed by planet Earth. More specifically, the ecological footprint per capita in global hectares – i.e. a nation’s total ecological footprint divided by the total population of the nation for a full list, see www.footprintnetwork.org/resources/data/ – are: Luxemburg 15.8; Australia 9.3; USA/Canada 8.2; Singapore 8; Belgium 7.4; Sweden 7.3; Oman 7.5; Estonia 6.9; Latvia 6.3; Israel 6.2; Austria 6.1; Mongolia 6.1; Finland 5.9; South Korea and Russia 5.7; New Zealand/Ireland 5.6; Japan/Norway 5; Botswana/Montenegro 3.8; Malaysia/Spain 3.7; China 3.4; South Africa 3.3; and Brazil 3. These examples illustrate the predominance of unsustainable consumption in countries where a majority of consumers are assumed to be affluent, in terms of having access to surplus income that makes it possible for them to consume in accordance with socially desirable consumption trends. However, the high ecological footprint of countries like Mongolia, with a relatively very low BNP per capita, illustrates that the biocapacity of the productive land and waste assimilation (Mongolia depends heavily on its mining industry, which produce waste) has a great impact on footprint analysis.

In sum, the ecological footprint analysis illustrates affluent consumption as intimately related to an ecological deficit which can be characterized as “importing biocapacity through trade, liquidating national ecological assets or emitting carbon dioxide waste into the atmosphere” (Global Footprint Network, 2016).

What unsustainable consumption, then, is characteristic of Western affluence? As mentioned earlier, not all affluent consumers consume in an unsustainable manner, even though they have the financial means to do so. However, large groups of affluent consumers do engage in highly unsustainable consumption practices that require large inputs of resources and energy. Brendan Sheehan (2010) describes in The Economics of Abundance the characteristics of an average affluent household: owned or rented decent accommodation; multiple cars, televisions, mobile phones, computers, washrooms and bedrooms; holidays abroad and credit cards; buying new, fashionable clothing each season; different meals every day and occasional meals out; fitted kitchen with fridge, dish washer, washing machine and freezer; plentiful supply and variety of children’s things, such as food, toys, clothes and electronic equipment; regular redecoration of the home and buying of a new car, personal grooming stuff, handbags, gadgets etc.; spending much of their leisure time shopping.

What this account does not tell us is that affluent consumption also demonstrates a tendency to acquire bigger residences, longer and more frequent holiday trips by plane, and more cars, mobile phones, computers, household apparel, sports equipment, furniture, clothes etc. (GfK, 2016; Statista, 2016). Thus, we as affluent consumers seem to be constantly engaged in the acquisition of products or variations of products already at our disposal. This means that affluent consumption not only reflects ownership of an increasing number of products, square meters and kilometres travelled per household but also a constant renewal of objects acquired and destinations.

European consumers mainly spend their increased income on services, travelling and recreational activities rather than on increased retail consumption (GfK, 2016). Swedish consumers’ expenditures increased by 23% 2004–2014, the greatest increases within the categories of furniture, interior design and maintenance (+57%), consumption abroad (+56%), personal communication (+50%) and recreational activities (+48%) (Konsumtionsrapporten, 2016). Consumer expenditure statistics can be translated into physical consumption. Swedish sales of private cars increased between 2001 and 2015 by 18%, which corresponds to 470 private cars per thousand inhabitants (Statistics Sweden, 2017). In 2015, Swedish consumers used an average of 3.4 connected electronic devices (Statista, 2016). Recent statistics show that Swedes buy on average 13 kilos of textiles (clothes and textiles for the home) per person per year. This represents consumption of approximately 50 pieces of clothing per person per year. Swedes like to wear new clothes. They throw away 7.5 kilos of textiles per person yearly, and 60% of this waste is made up of textiles that are not worn down or ragged, i.e. perfectly usable and quite new clothes are thrown away (Swedish Environmental Protection Agency, 2017).

In the UK, retail sales 2014–2016 increased approximately 3% yearly (Government of the United Kingdom, 2016). Each year in the UK 44 billion...