This is a test

- 2,056 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Varieties of Female Gothic Vol 1

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This text offers scholarly and critical editions of significant novels of Gothic fiction from the Romantic period. It illustrates the various forms of female Gothic literature as a vehicle for representing the modern forms of subjectivity, or complex and authentic inward experience and identity.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Varieties of Female Gothic Vol 1 by Gary Kelly in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Literary Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Mary Butt, The Traditions (1795)

THE TRADITIONS, A LEGENDARY TALE.

IN TWO VOLUMES.

WRITTEN BY

A YOUNG LADY.

A YOUNG LADY.

Since in history events are of a mixed nature, and often happen alike to the worthless and deserving; insomuch that we frequently see a virtuous man dying in the midst of disappointments and calamities, and the vicious end their days in prosperity and peace: I love to amuse myself with the accounts I meet with in fabulous histories and fictions; for in this kind of writings we have always the pleasure of seeing vice punished and virtue rewarded.

ADDISON.1

LONDON:

PRINTED FOR WILLIAM LANE, Minerva, LEADENHALL STREET.2

PRINTED FOR WILLIAM LANE, Minerva, LEADENHALL STREET.2

M.DCC.XCV.

TO MR. ST. QUENTIN.3

SIR,

THE motives, which have induced me to present in manuscript the following tale to Mrs. St. Quentin and yourself, will, I doubt not, give you both more satisfaction than any beneficial consequences from its publication. These motives, and the moral tendency of this humble composition, will, at least to you, appear a sufficient apology for such an attempt, at an early period of life, and for the many faults which must be expected, and will be found, in this tribute of genuine respect

From your late PUPIL, and sincere friend, THE AUTHOR.

MR. ST. QUENTIN presents his most respectful compliments and thanks to the Subscribers, for their liberal support, and will ever retain a most grateful sense of their kindness. He should have been happy (had he not been restricted) to have paid here a tribute of gratitude to the Author of the Traditions, as well as to those to whom, on the present occasion, he is under particular obligations.

Hans Place, Brompton,

May the 10th, 1795.

May the 10th, 1795.

THE TRADITIONS.

[VOLUME I]

CHAPTER I.

Know then this truth, enough for man to know,

Virtue alone is happiness below.

Virtue alone is happiness below.

POPE.4

BETWEEN the noble families of St. Alban and de Montfort5 unceasing animosities had prevailed for ages. Although frequent treaties of peace had been negotiated, and the chieftains of both houses had often met, and exchanged vows of eternal amity, yet upon the slightest pretexts they would again break out into open hostilities, and commit dreadful depredations on each other’s domains.

The wars between these contending chieftains at length arose to such a height, that Edward the First,6 enraged at the perpetual tumults which they occasioned, put a stop to them by a peremptory command, and banished the heads of both parties from the court. Rage, and a thirst of revenge, thus restrained by a superior power, gave way to silent hatred and cold contempt. At length two remarkable, and seemingly contradictory traditions, but of unquestionable authenticity, gave rise to very different sentiments on both sides. The late lord de Montfort, on his death-bed, while his son and daughter were weeping by his side, in broken accents uttered these words:

THE DAUGHTERS OF THE HOUSE OF DE MONTFORT SHALL SUFFER UNCOMMON MISERIES IN THE HOUSE OF ST. ALBAN.

At the same time a tradition of a very different nature was believed at St. Alban Castle. The present lord of that name had just married the lady Isabella Fitzalan, a descendant by the female line from the royal blood, a woman of excessive pride, and boundless ambition. While lord St. Alban was at the height of his joy on this occasion, and the walls of his castle resounded with festive gaiety, he was forewarned of his approaching death by some tremendous omen which he never could be prevailed upon to reveal. Often would he say, when the fair Isabella endeavoured by her enchanting smiles to dissipate his gloom: ‘No, this world will not long be my inheritance. Heaven indeed promises me a son, but soon after his birth I am doomed to part from all I hold dear. I shall not live,’ continued he with a deep sigh, ‘to see the union of de Montfort and St. Alban; but, praised be benignant Heaven, it will be effected by my son; and A DESCENDANT OF THE UNITED FAMILIES SHALL RESTORE THE NO LONGER HOSTILE HOUSES TO THE FAVOUR OF THE KING.

The lady St. Alban attempted by every method to dissipate his fears: sometimes she ridiculed them, but when this proved ineffectual, she endeavoured to drown the remembrance of them in a continual round of the gayest amusements. He, in the mean time, insensible to pleasure, could only find comfort in retirement, religion, and the conversation of his confessor, father Francis. He gave alms to the poor, confessed his sins, and, armed by penitence, looked with composure to his approaching end. And, indeed, the presages he entertained were but too true; lord St. Alban survived the birth of his son a few days only. When he perceived the approach of death, he entreated the lady Isabella, as he bade her an eternal adieu, ‘to be mindful of the wonderful tradition, and to seek a daughter of de Montfort for her son;’ then composing himself, poured out his last breath in prayers, ‘for the union of the hostile families, and the restoration of the royal favour.’

In the mean time, the young lord de Montfort, as soon as he had paid the last duties to the remains of his noble father, consulted his tutor, the Abbot of St. Kenelms, concerning the proper measures to be taken with his sister, the lady Philippa, to preserve her from the miseries which her father had predicted. ‘Place her under the protection of Heaven,’ said the Abbot, ‘in the neighbouring convent of St. Catherine.’ Lord de Montfort approved the plan, and resolved to execute it without delay.

Henry de Montfort, kinsman to the baron, who had been educated in the castle by the bounty of the late lord, no sooner heard of the intentions of his noble patron, than he flew to the apartment of the lady Philippa, and requested an interview with her. He had long entertained a passion for his fair cousin; but his dependent station placed him so far beneath her, that he had never before dared to avow it. Henry informed her of her brother’s intentions, painted to her in the most glowing colours the strength of his attachment, and in the strongest terms pointed out the horrors of a monastic life, and perpetual seclusion from the world. The gentle Philippa trembled, and requested his assistance to free her from this embarrassment. Emboldened by her condescension, he now ventured to persuade her to quit the castle with him that very night: she hesitated, but the terror of perpetual confinement at length overcame every other fear, and she that night escaped from the castle. And now its massive gates being once shut upon the lady Philippa, are to be opened no more. Enraged at her departure, lord de Montfort vowed never again to see her; but he was afterwards so far softened, as to allow her a small pension, and to take her little son into his protection. He insisted however, on this severe condition, that she should live in a retired situation, and conceal her name, and quality; threatening at the same time, that she should forego every advantage which he now proffered, if she ventured to appear on any part of his domain.

CHAPTER II.

Dr. BUTT’s Poems.7

SOON after the flight of lady Philippa, lord de Montfort married the beautiful sister of the lord de Mowbray.8 With this lady, who, from her mildness of temper, and gentleness of manners, submitted implicitly to the will of her imperious lord, the baron experienced no inconsiderable portion of happiness.

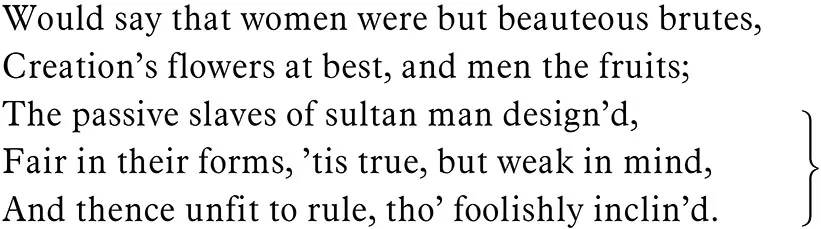

By the tranquillity which he now enjoyed, the fatal traditions were nearly effaced from his mind; at length, however, the painful apprehensions they formerly excited were renewed by the birth of two lovely daughters, one year after another. Instead of yielding to the sweet emotions of parental affection, he beheld the innocent babes with increasing horror, robed in the charms of innocence. They were in his eyes as lambs decorated for the altar. He had learned from report, that the young St. Alban daily improved in beauty, vigour, and every manly virtue; yet to de Montfort he appeared as a base deceiver, destined to effect the ruin of his devoted offspring. Often would he, from an apprehension of their fate, lean over their cradle with all the anxiety of paternal tenderness, as they slept gently on one pillow; while the small hand of the infant Emmeline was clasped by the rosy fingers of the elder Elfrida.9 In the presence of his children he endured extreme agony; and his anguish was increased by their absence, as they were then for a time withdrawn from his more immediate protection. Lord de Montfort at length resolved to consult the Abbot concerning the measures to be pursued with his infant daughters; that, if possible, the dreadful misfortunes with which they were threatened might be evaded; or, as he feared that the will of Heaven must necessarily be fulfilled in them, to concert with him the plan of education best adapted to enable them to meet with fortitude their future destiny. The Abbot had for some time withdrawn himself into solitude, that he might have leisure for religious meditation. On his arrival at the castle he found the lord and lady de Montfort together; he listened with the utmost attention while the distressed parents disclosed to him their fears, but declined giving them an immediate answer; saying, ‘that subjects of such importance demanded the maturest reflection.’ As soon as the Abbot found an opportunity of being alone with the lord de Montfort, he rebuked him severely for his imprudence, in permitting his lady to be present, while he conversed on affairs of such peculiar concern. ‘Women,’ he continued, ‘should be considered merely as beautiful paintings, or strains of melodious harmony, which for a moment gratify the senses, or enliven the drooping spirits, but leave not a lasting impression upon the heart, nor add to the real dignity of the human mind: however numerous their external charms, all is frailty within; they are in no respect worthy the confidence of the superior being, man.’

‘You are unjust to me,’ said de Montfort, offended at the sarcastic observations of the Abbot; ‘I am not ignorant of the weakness of the female mind, nor as yet hath any woman possessed my friendship.’ – ‘Women are naturally vain and fickle,’ rejoined the Abbot; ‘governed entirely by sentiment and caprice; they are born for subjection, and while they continue in their proper sphere, are at least harmless, if not amiable beings: but give them liberty, resign to their hands the rein of power, and they will run headlong into ruin.’10 ‘But,’ interrupted the lord de Montfort, ‘you fly from the purport of our conversation, it is concerning the education of my daughters that I want to consult you.’ – ‘You are mistaken,’ said the Abbot; ‘I do not wander from my purpose; in a good education, what must first be considered is the disposition of the pupil. When we have once thoroughly investigated that, the measures proper to be taken with it naturally present themselves. Your daughters should be brought up in privacy, and treated with rigour; their love of power should be restrained with the strictest curb; and their vanity and thirst for pleasure be checked by a life of the severest retirement: repress their boundless curiosity, by keeping them in entire ignorance; and as for employment, indulge them with a little music, or needlework; but, above all, let them attend their mother in her devotions, and learn betimes to honour the holy Virgin and the blessed saints. Permit not their little minds to be filled with learning; superficial knowledge is all that weak minds can at best acquire. Hence can it in no wise add to their happiness or virtue, and will serve only to cherish their natural vanity and pride. Pursue this plan, my lord, with your children, and, believe me, the predictions of your father will be fulfilled in them.’ – ‘So far, my father,’ replied de Montfort, ‘I agree with you, a woman proud of her learning is an object of contempt; but there is one point still to be considered. This mode of educating my children will provide for their safety during my own life, but will it ensure their virtue and happiness when I am no more, and they are at liberty to act for themselves?’ – ‘In good truth,’ said the Abbot, ‘that man is presumptuous indeed, who undertakes to answer for the fickle sex: but to use every precaution in your power, you would do well to marry one of your daughters early to your nephew, or any one you think proper; as for the other, consecrate her to Heaven in the convent of St. Catherine.’

The rest of this conversation is not related at large; it is sufficient to say, that lord de Montfort, in pursuance of this plan, fitted up for his daughters a remote part of his castle. Here they saw only the Abbot, who was appointed to superintend their education, their parents, and their female attendants: on these a strong injunction was laid, never to mention the name of St. Alban, or disclose any of those traditions which so painfully awakened the solicitude of their friends.

CHAPTER III.

Pride was not made for man: a conscious sense

Of guilt and folly, and their consequence,

Destroys the claim, and to beholders tells,

Here nothing but the shape of manhood dwells.

Of guilt and folly, and their consequence,

Destroys the claim, and to beholders tells,

Here nothing but the shape of manhood dwells.

WALLER.11

UNDER the direction of the abbot the two daughters of lord de Montfort were educated in pride, ignorance, and superstition. Their vanity was fostered by the adulation of their attendants, who were solicitous to gain their favour. By nature indeed they possessed every charm that attracts admiration, for their persons were lovely, and their capacities of a superior cast. The lady, their mother, paid too great deference to the opinions of the abbot, and of her lord, ever to interfere with the plan which they enforced; but the native gaiety and high spirit of the young Elfrida, could not be entirely restrained by the severity of the abbot. As much as possible she avoided his presence; when he spoke, she did not listen to his words, and in proportion as she disregarded his opinions, she cherished a proud conception of her own. Pride was the ruling principle of her conduct, and the means employed to suppress increased the haughtiness of her spirit. Sometimes the abbot endeavoured to restrain the proud sallies of her temper by cool contempt, or sullen inattention. At others, he attempted to solicit her to the imitation of those illustrious characters who, in compliance with the precepts of religion, humiliated their hearts, and paid implicit obedience to their spiritual directors, as the imperial Helena, the high-born Paula, the pious Eustochium.12 These he described as examples of angelic purity on earth; his austerity and his eloquence were equally inefficacious. Elfrida cherished in her heart the love of power, which, the abbot says, is ever triumphant in the female breast. And since he could not persuade, he determined for a time at least severely to control his pupil. As the abbot tyrannized over Elfrida, she in return kept the lady Emmeline in entire subjection. But what might seem a hardship was really a blessing to the lovely Emmeline; she bore with exemplary patience the caprices of her haughty sister. She complained not of her unkindness. Gentleness and humility, the truest ornaments of the female sex, were hers in the highest degree; and under the influence of these ever-endearing virtues, the imperfections of her education appeared less conspicuous.

By the Abbot’s plan Emmeline was destined to the seclusion of a convent. He endeavoured to prepare her for the gloom of a religious life, by every art in his power, and attempted to infuse into her simple heart the gross superstition which was mingled with hateful duplicity in his own. The natural good sense of the lovely Emmeline taught her to question some of his doctrines; she dared not, however, to suggest her doubts, but, as she cherished them in her own bosom, the whole of his lessons became odious to her.

These high-born sisters were now arrived at the bloom of youth and beauty, and as yet were ignorant of their father’s intentions respecting them. It was at this time that Alfred, the son of the lady Philippa, was expected to return from the Continent, where he had remained several years with the lord Mowbray, one of the bravest barons of that warlike age. Alfred had formed an ardent friendship with Edward, the lord Mowbray’s eldest son. These noble youths had entered the lists of chivalry together, and had already acquired great renown in several perilous engagements with the French: that nation had for some time been at war with England,13 but a truce was now concluded, and Alfred had written to his uncle, signifying his intention of returning soon to his native country.

Lord de Montfort had long designed to make Alfred his heir, by a marriage with one of his daughters; and the glory which he had recently acquired in arms, determined him to execute his project immediately after the arrival of his gallant nephew.

The abbot now urged him to communicate his plans to his daughters; he accordingly sent for them into his own apartment, and disclosed to them his intentions.

From the conduct of the abbot towards her, the lady Emmeline had long suspected what was to be her destiny. She had endeavoured to prepare herself for it. She had never participated the pleasures of the world, nor even indulged a hope of enjoying them; and where hope never was, there can never be regret. She received her father’s commands with submissive reverence. She bowed her head in...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- General introduction

- Introduction

- Bibliography

- Chronology

- Note on the texts

- The Champion of Virtue (1777)

- The Traditions (1795)

- Explanatory notes

- Textual notes