MYTH AND THE STRUCTURE OF MODERNITY

Recent critical work on the nature of modem law has emphasized the mythical elements inherent in its structure (see Carty, 1990, 1991; Derrida, 1990, Goodrich, 1990). As Fitzpatrick points out,

The mythic composition of law can be made out in its contradictory attributes. Law is autonomous yet socially contingent. It is identified with order yet it changes and is historically responsive. Law is a sovereign imperative yet the expression of a popular spirit (Fitzpatrick, 1992, p. x)

In an attempt to understand how modem law maintains its apparent unity in spite of those contradictions, Derrida, Fitzpatrick and others have focused attention on the ways in which Occidental being takes its identity in negation of certain primitive ‘others’. In this act of negation, Occidental being rejects external sources of meaning and value, and endows itself with deific properties of transcendence, universal being and infinite progression. In doing so, a mythology of the Enlightened Individual is evoked which serves much the same social functions as myth in ‘pre-modem’ societies.

Myth serves essential social functions. Far from being a mere superstition or fable, myth defines reality. It endows a society with sacred origins, identity and purpose. As Eliade notes,

Myth narrates a sacred history; it relates an event that took place in primordial time, the fabled time of the ‘beginnings’. In other words, myth tells how, through the deeds of Supernatural Beings, a reality came into existence ... Myth, then, is always an account of a ‘creation’; it relates how something was produced, began to be. (Eliade, 1963, pp. 5-6)

Myth also distinguishes between order and chaos, and between nature and culture; it establishes the power and symbolism of the ‘centre’; myth avoids the ‘terror of history’ by allowing a ‘return to origins’. Above all, myth mediates the contradictions of human existence. It transcends the divide between the particular and the universal, the profane mortal world and the sacred, eternal cosmos (see Adorno and Horkheimer, 1979; Eliade, 1965; Lévi-Strauss, 1963, 1986; Fitzpatrick, 1992). To accomplish this, archaic myth allows for human existence in separate and internally harmonious mythical realms. History is reversible: the profane can be purified, and environmental or social catastrophe remedied, in an ‘eternal return’ to the time of beginnings (Eliade, 1965).

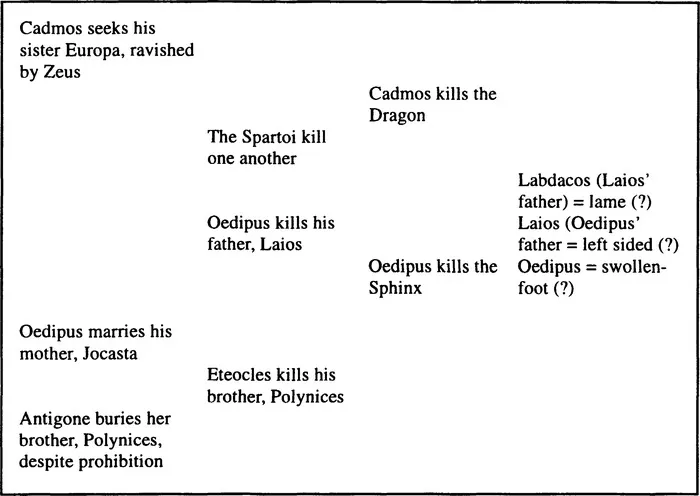

The analysis of mythic structures undertaken below corresponds largely to that pioneered by Lévi-Strauss (see Lévi-Strauss, 1963, pp. 206-12). This model comprises the following elements: (1) that the meaning of myth resides not in any one element, but in the combination of those elements; (2) that myth exhibits specific and more complex properties than mere ‘language’, i.e. beyond ordinary phonemes, morphemes and sememes; (3) that these elements, or mythemes, are primarily concerned with a relation between functions (or symbols) and subjects; and (4) that the true mytheme constitutes a bundle of relations which are simultaneously diachronic and synchronic, langue and parole, existing in both reversible time and irreversible time. It explains not only the past, but the present and future. For the sake of example, Lévi-Strauss’s famous deconstruction of the Oedipus myth is reproduced in Figure 1.1 (see Lévi-Strauss, 1963, pp. 13-218). The story is broken into four columns representing discrete types of relations.

Figure 1.1 Lévi Strauss’s deconstruction of the Oedipus myth

By disregarding one-half of the diachronic dimension of the Oedipus myth (left to right), and focusing only on the columns as a unit, the myth’s inherent meaning is made explicit: the first column relates to events which overrate the blood-tie; the second to its under-rating. Third column events relate to monsters being slain by men. In Greek mythology, monsters were seen as creatures whose death was a condition precedent to the emergence of humanity – a humanity born directly from the Earth itself (and not originally from the union of man and woman, thus autochthonous). This struggle is implicit in the battles with the Dragon and Sphinx, yet their contemporary existence is an implicit denial of the autochthonous nature of man. Conversely, the fourth column deals with elements of the myth which relate to lameness or difficulty walking. A common trait of world mythologies relating to the autochthonous nature of mankind is the newly arisen beings’ inability to walk, or to walk only clumsily. Thus the fourth column is linked by the affirmation of the autochthonous nature of mankind. Column four is to column three as column one is to column two. The self-contradiction of both pairings is overcome by recognition of the structural similarity of their contradictory attributes.

By a correlation of this type, the overrating of blood relations is to the underrating of blood relations as the attempt to escape autochthonomy is to the impossibility to succeed in it. Although experience contradicts theory, social life validates cosmology by its similarity of structure. Hence cosmology is true. (Lévi-Strauss, 1963, p. 216)

This form of reasoning, although logical (and indeed highly sophisticated) in its own terms, was anathema to Baconian and Newtonian models of scientific reason, which purported to supplant myth and superstition with scientific truth based on Cartesian principles of ‘rational’ mind. The supernatural gives way to the natural; religion to science and history; and society to the individual. Yet the structures of Enlightened thought betray a strong fellowship to archaic myth. By creating itself in historical time, rather than in sacred time, the sovereign individual of Enlightenment internalizes the ‘terror of history’ which it sought to avoid; internalizes it as part of its essential self (see Adorno and Horkheimer, 1979, pp. 27-30; Eliade, 1965, pp. 150-60; Fitzpatrick, 1992, p. 28). In doing so, the subject of Enlightenment (and ultimately of liberalism) becomes the self-reflective and unitary source of meaning and value. The subject itself transcends the contradictions between the general and the particular, fate and fortune, the profane and the sacred, by the mere fact of its existence, eternal progression and universal becoming. The tremendous contradictions inherent in such a claim, particularly in a society committed to scientific understanding, ‘rational’ enquiry etc., a society which ‘dared to know’, is resolved by defining itself not in terms of what it is, but in terms of what it is not.4 Derrida, writing of the impossibility of escaping metaphor in Western metaphysics, describes the phenomenon as the creation of ‘white mythology’ (Derrida, 1982, p. 213).

Thus ‘denigrated myth becomes the obverse of a Western world’, a world which ‘now took identity as the culmination yet negation of all that preceded it’ (Fitzpatrick, 1992, pp. 29-30). This identity is defined and opposed to certain primitive and myth-ridden ‘others’, in which Occidental being recognizes its own origins and away from which it advances in a constant progression. So constituted, the outstanding characteristic of modernity is raw human will, the ‘will to power’ as Nietzsche recognized.

The Enlightenment rejection (and implicit absorption) of myth is reflected in the structure of Western law and in the claims of unity, universality and progression made on behalf of its legal subject. Thus the ‘Sovereignty of the People’ is reflected in the power of positive law, yet the potential absolutism of that power is tempered by judge-made law which derives from other sources – reason, general principles etc. The inherent irreversibility of statute (and thus the reality of history and the contingency of life) is juxtaposed to the reversibility of the ‘good old’ common law (or Roman/Civil law) representing eternal reason. And within the latter, the subject-matter of the law inherently defines its legal subject. Such claims, of course, can themselves only be mythical. Thus the rejection of mythology in modem law is part of the mythology of modem law (Fitzpatrick, 1992, p. ix). Given the loss of a transcendent divine or natural law as the source of authority to substantiate its extensive claims, modem law and its legal subject takes identity from what it is not. And what it is not is the primitive, the particular and the myth-ridden.

Thus modern law emerges, in a negative exaltation, as universal in opposition to the particular, as unified in opposition to the diverse, as omnicompetent in contrast to the incompetent, and as controlling of what has to be controlled. (Fitzpatrick, 1992, p. 10)