![]()

1 The Robot as Cultural Meme

Film and science fiction (sf) have a long-standing, practically historical, and certainly telling connection. From the earliest days of film, and long before the genre even acquired its proper name, filmmakers were creating sf-like texts: accounts of marvelous journeys such as Georges Melies’ A Trip to the Moon (1902) and The Impossible Voyage (1904), futuristic visions like The Last Man on Earth (1924), and astounding inventions like those depicted in J. Stuart Blackton’s robot short, The Mechanical Statue and the Ingenious Servant (1907), and Mack Sennett’s The Inventor’s Secret (1911).1 Of course, many of these early titles simply remind us of the prior development of the sf imagination within the framework of a distinctly science and technology–inflected literature, illustrated most prominently by the work of Mary Shelley, Jules Verne, H. G. Wells, and even Edgar Allan Poe. But that kinship also owes much to the very nature of film. As an art form made possible by scientific and technological advances—that is, as a scientifically driven fiction—it initially developed in the context of what historian Tom Gunning has termed a “cinema of attractions” (63), that is, as texts built around—and thus reflecting—the amazing technical ability for image reproduction and fantastic illusion that was the early cinema’s stock-in-trade. In the developing genre of sf, film simply found both a natural ally and a rich resource that it could readily mine for such attractions.

Our efforts to study that sf cinema, however, have often tripped over what, in the years since the genre’s development, has become an increasingly knotty relationship—of film, sf literature, sf in popular culture, and more broadly, the sf imagination. Such efforts have especially been complicated by our disciplinary vantages, because those interested in and knowledgeable about sf in its literary and cultural artifact versions often have little or only passing concern with the cinema, whereas those invested and trained in cinema or television studies often pay little attention to the literature, theory, and the broader culture surrounding sf, save perhaps in instances when that material intersects with the large field of genre studies. Some of this disjunction is understandable, because the work of visual sf tends to be very different from the work of, for example, sf literature, whereas the broader interests of sf, or what I shall keep referring to here as the sf imagination, usually seem to bulk beyond the historical and theoretical concerns of film studies. In fact, even something as fundamental—and certainly a potential meeting ground—as one of sf’s often-acknowledged core appeals—its ability to provide audiences with what Michele Pierson and others have termed an “aesthetic experience of wonder” (168)—seems to operate quite differently as we move across media or shift focus to different elements of popular culture.2

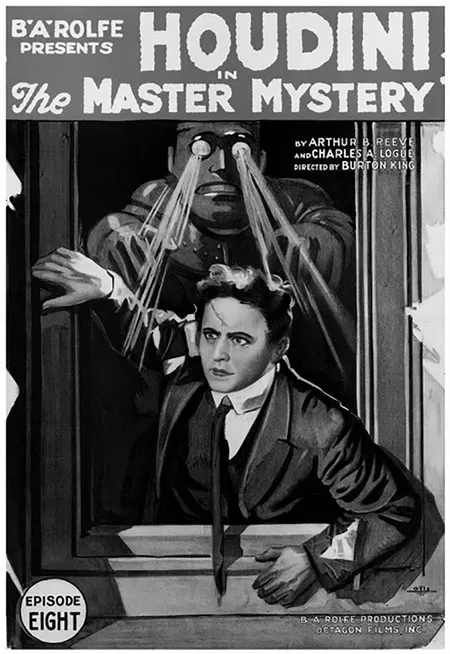

Figure 1.1 The mysterious metal man menaces Harry Houdini in The Master Mystery (1919). Octagon Films.

What I want to do here is explore a small portion of this tangled territory by slipping across some of the usual boundaries of study. In fact, my perspective might seem somewhat paradoxical, because it involves examining just a single image, that of the robot/android/cyborg/replicant, as it has taken hold in that sf imagination and found a particularly central place in our sf films. Because my own primary interest is in film studies, and because the image of the robot has resonated with such special power in our cinematic texts, I want to survey this territory primarily from that vantage. But doing so, as we shall see, also allows—or at least invites—us to consider a number of other elements implicated in the sf imagination’s robotic vision—elements that together constitute what I would like to describe as a “robot ecology” of the sf film. Although grounded in the cinema, then, the following efforts to describe the broad outlines of that ecology will involve us in considering, or at least acknowledging, a variety of other components, including sf literature and theory; other cinematic genres; and other media forms, such as television, graphic arts, advertising, stage shows, toys, etc.—all of them components in that robot ecology, all of them helping to constitute in the popular imagination what has become one of the most important tropes in sf and arguably the most powerful image of the sf cinema. The hope is that by following the track of this artificial figure, we might find along this tangled path a productive way of considering some of the linked elements that have informed not only the development of the robot image, but also other components of our sf cinema, all of which together help constitute that sf imagination and the story it tells about the robot.

A primary reason for taking the robot as a stalking horse here is because it has attained a status that resonates not only with some of the key concerns of contemporary culture over the last century, but also, as I have already implied, with the very nature of film. Although the robot has, of course, given us a vehicle for exploring issues of gender, race, and a variety of forms of Otherness, and increasingly for asking questions about the very nature and meaning of life, this image of an artificial being, most commonly anthropomorphic in form, also invariably implicates the cinema’s own and quite fundamental artificing of the human. For despite the common impression that film essentially mirrors the real, it is, as we well understand, always presenting even the human image through a process of various technological constructions as artifice: as something chemically reproduced on a film’s emulsion (or rendered in pixels by a computer, the confusing potential for which we see explored in the 2002 film S1mOne); as visually fashioned from a combination of long, medium, and close-up shots, at times even cobbling together parts of different bodies through those different shots, as with Arnold Schwarzenegger’s face and a younger actor’s body in the recent Terminator Genisys (2015); and as enhanced by a mix of artificial lighting, color manipulations, prosthetic appliances, and various sorts of digital “enhancements,” resulting in bodies—such as those rather spectacularly realized in the comic book adaptation 300 (2007)—that ultimately do not correspond to any we might encounter in the real world. Although some might simply suggest that this point means little, because most film actors are, after all, rather “robotic” themselves, that all film understandably trades in various sorts of illusion and reconstruction, or that all film bodies—not to mention our own imaginations—are invariably “cinematized” in one way or another, we would do well to note this dimension of the robot, this fundamental filmic correspondence. For it binds together at a most basic level the work of both sf and film, speaking directly to one of the sf genre’s ultimate aims, while reminding us of ways in which the very medium always implicates a large part of that sf aim: the genre’s consistent efforts to measure out, whether for today or tomorrow, the impact of science and technology on our humanity.

In this investigation, then, we are going to look through the lens provided by that robot figure in order to see a bit more deeply into the relationship between sf and the cinema—a relationship bound together by that sf imagination. This particular figure’s longevity, dating from a time even predating the introduction of the term robot ; its recurrent focus on certain conceptual issues, such as those of gender, class, and power; and its ability to conceptually develop or produce offspring, such as the various androids, cyborgs, and replicants found throughout our films today, attest to both the robot’s place in and influence on the cultural imaginary—effects that have, in fact, allowed it to distribute meanings across a wide range of media texts and that thus reward our considering a sampling of those varied texts, describing, at least in part, what I term a robot ecology. But film’s manifest fondness for this particular “attraction”—a fondness partially measured by the robot’s appearance over the years in a broad array of films, including cartoons, live-action comedies, musicals, murder mysteries, and horror films, as well as our sf narratives—also suggests something of its medium’s singular capacity for, as Francesco Casetti eloquently offers, “intercepting the impulses of twentieth-century modernity,” guiding them “in a particular direction, regulating their intensity, combining them, tying them to certain patterns or exigencies … giving them a model against which the spectator could compare him or herself” (5). Consequently, we shall need to see the cinematic robot as more than simply a descendant of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein monster (1818), more than a technological evolution of something like the title figure of Edward S. Ellis’ dime novel The Steam Man of the Prairies (1868), and more too than a holdover from or descendant of that early “cinema of attractions” of the 1890s to 1910s. It is, in fact, something of an image of film’s own development, of what has been increasingly shown to be its own rather sf-ish nature.

I want to organize and explore this tangled relationship, as I have described it, not by surveying the robot in all its history and variety, but rather by looking systematically at certain dominant types of robots in order to better understand their implications for film, science fiction, and even contemporary culture. Consequently, I do not want to suggest that, despite a roughly chronological treatment, what follows is a history of either the robot or of sf film. In an earlier and rather traditional approach to this figure, I used the image of the artificial being in much this way, as a conventional diachronic measure, a way of focusing on particular achievements in the larger history of sf cinema and weaving those achievements together to form a roughly representative genre history. Given the lack at that time of a good history of the sf cinema, providing that sort of chronicle was my primary concern. To work up to that history, I began by observing how versions of this image of human artifice have been a part of Western culture from the time of the ancient Greeks to the present, an important touchstone in sf literature, particularly as it developed in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, and an almost constant presence in our sf films—indeed, one of sf cinema’s most common semantic conventions found, as we have already noted, even in its earliest days. My belief was that because of this almost constant presence and the way it aligned the human figure with the powers of science and technology (as both the originator of those powers and, quite often, their “beneficiary”), the artificial being could help us chart the film genre’s development or, more precisely, the various ways in which cinematic sf has evolved, while using the robot to address various key concerns, among them our cultural anxieties about the work of science and technology, our human concerns about the body, and especially in more recent years, its commonly gendered and racial identity, and even the changing nature of the technology-dependent art of film itself.

However, while that previous “robotic history,” as I termed it, allowed for the glimpsing of various other implicated histories and suggested some intriguing links, it invariably came up short in several obvious ways. One was with accounting for how that artificial, robotic figure held on to our imaginations—and our films—sometimes for decades, before suddenly coming to seem rather quaint, rather like a nostalgic figure of film history, an aged but beloved performer/star, as it were. A second was with its seemingly easy ability to reach across genres and media, to become—and here I want to borrow a useful metaphor from the recent work of Henry Jenkins, Sam Ford, and Joshua Green—a kind of “spreadable” trope,3 able to inhabit different parts of the media landscape, easily extending its sf character in a variety of directions and providing meanings for different sorts of audiences, including a non-sf audience. A third was with adequately explaining the relationships between one sort of robot “performance” and another, with talking about their particular connections rather than their function as chronological signposts in a larger generic/cinematic development. What I hope to do here is to address these, as well as several other concerns, not so much to revise that earlier history, but rather to provide in brief form some of the critical texture that it, as well as similar studies, lacks.

In order to do so, I want to frame this discussion in the fashion of a “robot ecology” (and thus as a supplement to that earlier “robotic history”). I use this term to indicate an examination of the cinematic robot not simply as a generic icon with a long pedigree, but rather to designate its relationship to other parts of its real and cinematic “environment,” including literary and cultural components where those are most pertinent, elements that contribute to the larger sf imagination’s ruminations on how science and technology affect our humanity. Some of these “other parts” include a rising tide of machine/technological consciousness throughout modern culture, a tide that has led some historians and theorists to describe sf as the fundamental literature of technical/industrial culture; the development of sf as a distinct genre, using its key tropes or icons in ever more sophisticated ways; and the gradual proliferation of computers, or “thinking machines,” in our culture and in the world of entertainment. As Neil Postman, one of the leading figures in establishing this ecological perspective, has offered, the ecology of a thing or a medium “includes not only its physical characteristics and symbolic code,” but also “the conditions in which we normally attend to” that subject, conditions that are typically “accepted as natural” (79), taken for granted as elements of the cultural air that we breathe, but that, as a result, often go almost unnoticed. Yet they are, as he argues, part of a complex system—much like the biological environment—that implicates and even requires from us certain ways of thinking about or responding to a subject, in this case the increasingly insistent figure of the robot. In fact, I would suggest that we take this notion of required thinking in a double sense, as suggesting not only how certain elements of our cultural ecology prompt us to think in certain ways, but also how those elements make it increasingly imperative that we give thought to them and their operation on us—a point I hope this short monograph can begin to advance.

To help us move from Postman’s more general sense of the term to a more media-oriented approach, what follows relies heavily on Matthew Fuller’s Media Ecologies, which, as his plural use of the term might suggest, looks at various mixtures and interactions of media and media systems. In fact, Fuller cautions from the start that the term ecology has been used “in a number of ways” and has consequently become rather “ambiguous … given its number of different uses” (2–3). For example, although Fuller employs it to describe the workings of pirate radio stations in the United Kingdom, he also applies the term to organize a discussion of different surveillance and crime reporting mechanisms. Another practitioner, Jane Bennett, uses the principle of ecology rather differently—but quite effectively—to “articulate a vibrant materiality” of inanimate objects that, she suggests, almost invisibly “runs alongside” the human realm (Vibrant viii). Drawing on these and other examples, I emphasize ecology’s special ability to incorporate difference, to designate and examine what Fuller describes as “dynamic systems in which any one part is always multiply connected … and always variable, such that it can be regarded as a pattern rather than simply as an object” (4).

The focus of this study, as I earlier suggested, is itself multiple, keyed at times to particular robots in specific films or media texts, but more often concerned with robotic types or patterns as they have developed and persisted in the cultural consciousness—for example, in different genres (musicals, serials, science fiction, animation), in different media (not just film, but literature and television as well), and in different time periods (from the early twentieth century to the present). And because of those necessarily multiple connections (and multiple connections to multiple connections), what follows makes no claim to being an exhaustive analysis—the robot ecology. In this brief, demonstrative volume, we could not follow every cultural synapse that our robotic image might cause to fire within the sf imagination. So although we shall gloss over much of this figure’s literary development, which has been treated elsewhere, we shall also draw into the discussion some particularly telling elements from the realms of popular culture—advertisements, journalistic accounts, toy lines—while omitting others, all in order to focus more precisely on the patterns noted earlier, especially on the visual appearances that help constitute its cinematic context. The study that follows simply offers—hopefully—a telling view of the dynamic sf and cinematic system in which the robotic figure has come to play such a central and allusive role.

Further following the method demonstrated by Fuller, Bennett, Susan Blackmore, and others, our ecological discussions of the robotic figure will be organized within a “memetic” scheme; that is, I want to consider the robot as a kind of cultural “meme” and thus draw upon the characteristics typically used to describe it. A meme is a term originated by evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins, who offered it as a useful way of speaking about ideas or concepts in the same fashion that we have come to talk about genes and their biological functions (and one that, I want to suggest, might be equally useful for considering the nature of another gene near-rhyme, the genre). Explaining that parallel conception of gene and meme, Dawkins suggests that we think of the latter as a significant cultural concept that is subject to “cultural transmission,” an analogous process, as he explains, “to genetic transmission in that … it can give...