This is a test

- 281 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

In this first critical, multidisciplinary assessment of recent privatization in a developing country, the contributors offer valuable lessons for the comparative study of denationalization and related public policy options. After an introductory survey, the volume presents broad perspectives on the context, formulation, and adjustment of privatization policy in Malaysia. The contributors review the distributional implications of specific privatizations for the public interest as well as for consumer and employee welfare. The book concludes with an examination of the economic, political, and cultural impacts of the privatization of physical infrastructure, telecommunications, and television programming.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Privatizing Malaysia by Jomo K S in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Public Policy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Background

CHRISTOPHER ADAM and WILLIAM CAVENDISH

Malaysia is a lower middle-income economy of approximately 19 million people, of whom 60 percent are indigenous (known as the Bumiputera), mainly Malay, and the remainder non-Malay (principally Chinese and Indian). Its GNP per capita in 1992 was RM7543 (US$2900), The two decades since 1970 have witnessed a period of significant growth in the Malaysian economy, in line with other emerging newly industrializing countries (NICs). However, during the mid-1980s, the economy experienced a severe recession, following a 17 percent deterioration in the terms of trade between 1981 and 1982. The current account deficit grew dramatically during the period, the public-sector deficit, which had averaged approximately 10 percent of GDP during the first New Economic Policy1 (NEP) decade (1971-1980), reached 21.7 percent of GDP in 1982, and between 1984 and 1985, real growth fell from 8 percent to -1 percent. The subsequent recovery saw the economy returning to higher levels of activity, with real GDP growth rates at 5.3 percent for 1987-1989 and averaging over 8 percent during 1988-1993.

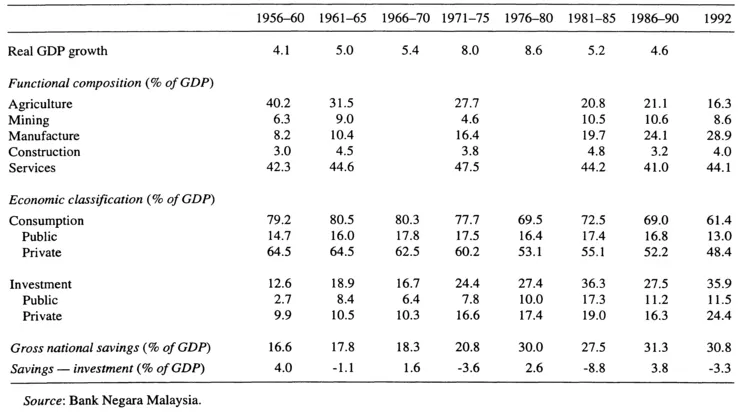

Gross domestic savings levels in Malaysia are particularly high, averaging approximately 29 percent of GNP during the 1970s and 1980s (Table 1.1), and exceeding 32 percent in 1992. However, much of this saving is contractual. In particular, the largest single savings institution, the Employees Provident Fund (EPF), accounts for approximately 20 percent of total employment income, while the investment trusts of the Permodalan Nasional Berhad (PNB) and the Islamic savings institutions attract a further large proportion of these savings.

As Table 1.1 indicates, the investment to GDP ratio has risen rapidly since Independence, and averages approximately 31 percent of GDP, having exceeded 40 percent in 1982-1983. Since the introduction of the NEP, the public-sector share of total investment has risen dramatically, reaching a peak during the early 1980s, when, for the only time since Independence, public-sector investment2 accounted for 50 percent of total investment in the economy. The economic restructuring program, combined with the development of a more private sector-oriented

TABLE 1.1 Composition of Gross Domestic Product 1956-1992 (percentage)

development strategy, has seen public-sector investment drop back sharply since 1986.

Malaysia is a resource-rich economy, both in terms of oil and natural gas as well as non-mineral resources. Yet, despite this, its development since Independence in 1957 has been based on a broadening of its production and non-traditional export sectors. At Independence, the economy was dominated by the agricultural sector, which accounted for over 40 percent of GDP, 60 percent of formal sector employment, and almost 70 percent of export earnings. In particular, Malaysia was the world's largest producer of natural rubber and tin. Over time, however, though remaining a world leader in these two commodities, the country has successfully diversified activity across its broad resource base, and has seen the emergence of the petroleum industry and other manufacturing activity, which between them now dominate the economy. Real growth in the manufacturing sector averaged 10 percent per annum from Independence until the early 1980s, and although the sector's growth declined during the economic slowdown and recession from 1982 to 1986, recovery since 1986 has been rapid, with growth rates exceeding the pre-recession period.

Throughout the period from Independence until the late 1960s, the emphasis was on import substitution, but during the 1970s there was a shift towards labor-intensive and high-technology export-oriented production, to the extent that manufactured exports now account for over 50 percent of all exports. The 1980s saw even greater emphasis on the manufacturing sector, especially as Malaysia has developed an increasingly outward-looking stance, although there was some reorientation in the early 1980s towards the growing domestic market, especially in the capital-intensive and consumer durable sectors. The severity of the recession of the mid-1980s added extra stimulus to the need for even greater diversity in the economy, and has been followed by renewed measures aimed at greater liberalization of the domestic economy, the reduction of the role of the public sector in the economy, and the rejuvenation of foreign participation in the domestic economy.3

Structural Constraints and the New Economic Policy

One of the most pervasive problems of the economy, and one which has widespread implications for the privatization program as a whole, is the extent to which political structures create barriers to efficient intermediation of commercial risk. Consequently, domestic risk aversion is exacerbated, leading to low levels of investment in productive activities (relative to aggregate savings). Investment opportunities abound in Malaysia; there are skilled human resources, both industrial and managerial, and a sophisticated financial sector, capable of raising capital domestically and internationally. In addition, the economy is well served by transport and other communications systems. Despite this, however, and as a result of historical factors and the philosophy underpinning the New Economic Policy, the economy, and the financial system in particular, function so as to divert risk capital away from private-sector investment towards non-productive, public-sector activities. Furthermore, even when funds are directed towards domestic investment, business licensing and employment practices create barriers to efficiency and competition in the private sector. At this stage it is necessary to establish the context for much of the analysis to follow by outlining the origins of the New Economic Policy, and its impact on the economy.

From Independence until 1970, the political economy of Malaysia was shaped by the so-called "Bargain of 1957", This was an agreement between Malay and non-Malay (i.e. Chinese and Indian) interest groups which allowed the latter a relatively free hand to pursue their commercial interests while the Malays retained political control, through which a degree of positive discrimination was exercised (mainly through public-sector employment policies). However, following race riots in Kuala Lumpur in May 1969, sparked off by growing resentment of Chinese domination of the economy, the predominantly Malay government moved quickly to develop an economic program of affirmative action towards the Bumiputeras. The New Economic Policy was the embodiment of this affirmative action program and was immediately integrated in the Second (1971-1975) and subsequent Malaysia Plans.4 In doing so, it fundamentally altered the course of macroeconomic policy-making for the next two decades. The NEP outlines the objectives of economic policy as "(i) the promotion of national unity and integration; (ii) the creation of employment opportunities; and (iii) the promotion of overall economic growth," noting that "the economic objective of national unity may be expressed as the improvement of economic balances between the races or the reduction of racial economic disparities" (NEP quoted in Faaland et al., 1990: 307).

Though the NEP embodied a broad range of socio-economic objectives such as employment, housing, education, and an exclusive civil service recruitment policy, the litmus-test was, and remains, the distribution of corporate asset ownership as the indicator of wealth distribution. In 1970, 62 percent of all corporate assets were owned by foreigners, 34 percent by non-Bumiputera Malaysians, and 4 percent by the Bumiputeras (PNB, 1990). The NEP consequently set target equity ownership lev...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Acknowledgments

- Contents

- Tables

- Figures

- Abbreviations

- Introduction

- 1. Background

- 2. Overview

- Part One: Macropolicy Perspectives

- Part Two: Issues

- Part Three: Sectors

- Bibliography

- About the Book

- About the Contributors

- Index