![]()

1 Introduction

A Chinese landscape in the age of globalization

The starting point of our story is President Trump’s intriguing question about whether Apple and other companies could bring manufacturing back to the U.S., particularly from China. Our basic argument is that, despite its ongoing dependence on foreign technologies and IP, China has been upgrading its ICT sector through participating in the GVC. Specifically, this chapter investigates China’s open economy, high-tech industries and indigenous innovation. Finally, it describes the objectives and organization of this book.

Background and viewpoints

Trump’s promise

On January 18, 2016, in a campaign speech at Virginia’s Liberty University (a private, Christian school), Donald Trump, Republican Presidential candidate, tangentially promised that he would force Apple to manufacture its hardware in the United States (U.S.) instead of looking to overseas labor (The Washington Post, 2016). When American companies moved manufacturing to China, it was all about cost, according to Trump. China’s wages were amongst the lowest in the world and its government provided subsidies and turned a blind eye to labor abuse and environmental degradation. Now, only the Mac Pro is currently assembled in the U.S., in a factory located in Austin, Texas. Apple otherwise relies on manufacturers in China for most of its products, both because of cheap labor and because decades of previous outsourcing has allowed the American manufacturing industry to shrink.

But now, cost competitiveness is changing worldwide. BCG’s report – The Shifting Economics of Global Manufacturing, published in 2014 – indicates that China’s estimated manufacturing-cost advantage over the U.S. has shrunk to less than 5 percent. The 2016 Global Manufacturing Competitiveness Index published by Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu Limited and the Council on Competitiveness in the U.S. indicated that China was ranked as the most competitive manufacturing nation in 2016, but that the U.S. is expected to take over the number one position from China by 2020. Meanwhile, one of the first executive orders of the new U.S. President was to end the United States’ participation in the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), while at the same time to begin renegotiating the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). By seeking to fulfil his campaign promises by bringing manufacturing jobs which were lost through offshoring back to the U.S., Trump raises the intriguing possibility of pressuring companies like Apple to reshore jobs from China.

China and the U.S.

In the wake of the financial crisis, China must face the reality that the world is now characterized by the de facto G2 of China and the U.S. These two major economies must find ways of collaborating, both in their own interests and to solve global problems and realize that trade protectionism and economic nationalism pose major threats to the global economy. Labor, real estate, and energy costs in the eastern urbanized regions of China have increased to the point that they are now comparable to some parts of the U.S., while China’s other advantages are also being eroded with the result that China is currently a more expensive manufacturing location than Indonesia, Thailand, Mexico, and India. At the same time, there is no evidence that Apple wishes to leave China, which is its second largest market. While its May 2016 investment of $1 billion in Didi Chuxing – a China-based company and Uber’s main rival – may have influenced Uber selling its China business to Didi Chuxing in August 2016, Apple clearly saw an important market opportunity. It also suggests a willingness by Apple to further contribute to China’s development.

Meanwhile, China is no longer content to be merely a global manufacturing base and the largest market. China is seeking to move to ‘Created in China’ from ‘Made in China’. The objective is to become an innovation powerhouse by 2020, according to the newly adopted 13th Five Year National Plan on Scientific & Technological (S&T) and Innovation (2016–2020). The plan aims to substantially improve China’s technology and innovation capabilities and lift the national innovation capabilities into the world’s top 15 (The China Daily, 2016). Apart from adding ‘innovation’ to the title, three points in the latest plan are worthy of note. First, China will continue to implement major S&T and innovation projects. The plan called for efforts to accelerate the implementation of major national scientific and technological projects and launch the scientific and technological innovation 2030 project. It puts research emphasis on areas that will contribute to China’s industrial upgrading and new economy, including modern agriculture, clean and efficient energy and fifth-generation mobile telecommunication (The State Council, 2016).

Secondly, China emphasizes innovation localization. The country should support Beijing and Shanghai to build scientific and technological innovation centers with international influence, set up a batch of innovative provinces and cities and regional innovation centers, and promote the innovative development of national indigenous innovation demonstration zones, as well as new and high-tech development zones.

Finally, China also stresses innovation globalization. The plan also urged the building of a Belt and Road innovation community aiming to improve the country’s ability in the allocation of global innovation resources and to fully participate in global innovation governance. While the Trump administration seeks to bring job opportunities from China to America though trade protectionism and economic nationalism, the Chinese government plans to improve its innovation capability and upgrade its industries.

Our arguments

Indeed, whether Apple could bring manufacturing back to the U.S. or move its manufacturing out of China may not be the right question. This action depends not only on China and the U.S., but also on the whole ecosystem of production and research in East Asia. In a more globalized economy, gross domestic product (GDP) and trade exports do not completely reflect a country’s competitiveness. More attention needs to be paid to explaining how a country like China has increased its involvement in global value chains (GVCs) and the extent to which it has contributed to and benefitted from this involvement.

In particular, this book seeks to investigate China’s involvement in GVCs from the perspective of the ICT sector. To what extent does China continue to be dependent on key foreign technologies, and how can China make greater progress in acquiring intellectual property (IP) ownership, more influence in the technology trajectory and greater value-added in GVC functions within China? Is GVC participation helping China to transition its economy from the low value-added tasks of being the ‘world’s factory’ to greater levels of indigenous innovation, and greater technological autonomy? How difficult is it for a latecomer nation like China to achieve upgrading within high-tech sectors such as semiconductors, which are global in nature?

Our basic argument is that, despite its ongoing dependence on foreign technologies and IP, China has been upgrading its ICT sector through participating in the GVC

While we would suggest that our argument presents a moderate view of recent developments, it also reflects what has been the de facto situation in China for some time. Although it can be argued that China’s ICT industrial output and exports have increased rapidly, and that China has become the largest global base for ICT manufacturing, this does not reflect the complete picture of China’s innovation capabilities and competitiveness. While others argue that China’s ICT development, in the absence of core competence, has been largely based on foreign equipment, technologies and IP, this does not preclude the fact that Chinese firms, through their involvement in GVCs, have acquired significant knowledge from foreign companies.

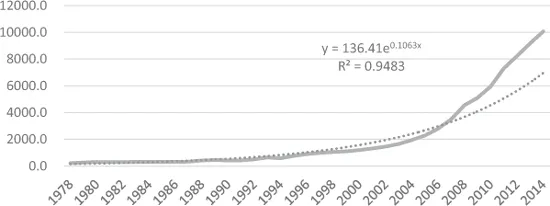

China’s open economy

Since initiating market reforms in 1978, China has shifted from a centrally-planned to a market-oriented economy and has experienced rapid economic and social development. GDP growth has averaged nearly 10 percent a year – the fastest sustained expansion by a major economy in history. China’s GDP reached USD 10 trillion in 2014, valued at the prevailing exchange rate, and it has become the world’s second-largest economy, having passed the industrial economies of the United Kingdom (UK), France and Japan since 2011 (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 China’s GDP growth since 1978 ($ billion)

Globalization, a necessary context of China’s economy

An extensive literature has developed seeking to explain how Chinese economic reforms have led to rapid growth. Lin et al.’s (2003) book provides background on the Chinese economic system under Chairman Mao and then explores in detail why the reformed system is better suited to China’s labor-rich, land-scarce resource endowment. The book is also unique in that it provides a balanced picture in several respects, explaining for example how both rural and urban reforms have permitted China’s comparative advantages to emerge in response to market signals. Wu (2005) provides a systematic discussion and comprehensive review of China’s economic reform through 2002. Among the topics explored in the book are the origins of central planning, problems that emerged and the gradual evolution of the reforms, with particular reference to rural reform, state-owned enterprises (SOEs) reform, the development of non-state sectors, the reform of the banking system, the development of the financial markets, fiscal and taxation reform, and reforms related to trade and foreign direct investment. The section on ‘opening to the outside world’ discusses the role of trade development strategies and foreign direct investment in China.

Naughton (2006) argues that China’s economic development can be traced to two incomplete transitions. First, China is still completing its transition away from bureaucratic socialism and toward a market economy. Second, China is in the middle of the industrialization process, the protracted transformation from a rural to an urban society. These two transitions are both far from complete, and so China today carries with it parts of the traditional and socialist, the modern and the market, all mixed up in a jumble of mind-boggling complexity. The book analyzes the reforms in several aspects: the rural economy (rural organization, agriculture, rural industrialization), the urban economy (industrial ownership and governance, technology policy and the knowledge-based economy), China and the world economy (international trade and foreign investment), and macroeconomics and finance (trends and cycles, financial system). Naughton’s work is also valuable for his explicit discussion of the two distinct phases of the reforms – the ‘reform without losers’ phase until about 1993 and the ‘reform with losers’ phase since then.

Indeed, these books contributed significantly to understanding how and why China has succeeded in many ways. Lin et al. (2003) focuses more attention on reform rather than opening-up. Both Wu (2005) and Naughton (2006) refer to the opening of the Chinese to varying degrees. Since China was only beginning to participate in globalization at that stage, it had limited impact on the world economy. But now globalization is an inevitable aspect of China’s economic development. On the one hand, many multinational companies (MNCs) have moved their production bases into Mainland China, which helped to promote China’s rapid economic growth. On the other hand, China has become an important location for global production networks, with Chinese firms participating in the global value chains of various industries. In this sense, globalization is an important part of the context of China’s rise, and it provides a useful approach for understanding China’s economic growth.

WTO: the accelerator of China’s globalization

After accession to the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001 and particularly since the international financial crisis in 2008, China emerged as a leader in the world economy, moving gradually towards an open economy. At the early stage of opening-up, China’s economic development depended very heavily on inward FDI and on exports. China’s uniquely gradualist reforms produced high levels of inward FDI, while both GDP and export growth in turn impacted on outward FDI and imports. Since 2001, China has gradually become a more open economy. Yet, according to the OECD FDI regulatory restrictiveness index (FDI Index), China’s index was the highest of the 58 countries measured at 0.39, compared to 0.05 for Japan, 0.06 for the UK and 0.09 for the U.S. Despite this, however, China ranked number two on the 2016 AT Kearney Foreign Investment Confidence Index at 1.82 after the U.S. at 2.02.

China’s increasingly liberal attitude toward inward investment resulted in extremely high rates of inward FDI, substantially higher than rates achieved by other economies in transition. Even in per capita terms for a country with over one billion inhabitants, China achieved inward FDI of $18.20 per capita for 1989–1995 (Liu et al., 2005). In 2014, China overtook the U.S. as the top destination for FDI for the first time since 2003. Foreign firms invested $128 billion in China, and $86 billion in the U.S. in 2015 (UNCTAD, 2015). Generally, China has garnered considerable attention for attracting global direct investment since the 1990s, with its share of FDI increasing to 9.0 percent of the global total in 2012 from 2.9 percent in 2000 (Rosen, 2014, 144). Certainly, the mainstream of existing studies suggests that the role of FDI in Chinese economic development has tended to be strongly positive. Recent research shows that FDI in China has indeed promoted economic development by improving allocative efficiency, but it has also had unfavorable effects, such as worsening productive efficiency (Lo et al., 2016).

More recently, China became a major source of outward FDI (OFDI) (Table 1.1). Chinese levels of OFDI were insignificant before 1985, but in the 1990s they averaged $2.3 billion per annum. While the scale of China’s OFDI is comparatively small compared with the U.S., the trend is steeply upwards, and China’s peak annual OFDI of $116 billion in 2014 was second only to $317 billion for the U.S. (UNCTAD, 2016). An important aspect of China’s OFDI strategy is the acquisition of key technology capabilities in areas such as semiconductors. The Committee on Foreign Investment in the U.S. (CFIUS) has been quite active recently in preventing a number of attempted acquisitions in the U.S. by Chinese companies, including Fairchild, Micron, Global Communication Semiconductors (GCS), Lumileds, Western Digital and Aixtron. There is a widespread fear in the U.S. that the acquisition of su...