A Poetics of Postcolonial Biblical Criticism

God, Human-Nature Relationship, and Negritude

Aliou Cissé Niang

- 232 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

A Poetics of Postcolonial Biblical Criticism

God, Human-Nature Relationship, and Negritude

Aliou Cissé Niang

About This Book

Telling in current biblical postcolonial discourse that draws insights from the works of Aime Cesaire, Frantz Fanon, and postcolonial theorists is the missing contribution of Leopold Sedar Senghor, the architect of Negritude. If mentioned at all, Senghor is often read through conclusions drawn by his critics or dismissed altogether as irrelevant to postcolonialism. Restored to its rightful place, Senghorian Negritude is a postcolonial lens for reading Scripture and other faith traditions with a view to reposition, conscientize, liberate, and rehabilitate the conquered, and enable them to reclaim their faith traditions and practices that once directed a mutual relationship between God, human, and nature--a delicate symbiosis before the French colonial advent in West Africa. A keen eye for cross-cultural analysis and contextualization enriched this volume with an intriguing reading of scripture, Ancient Near Eastern and Greco-Roman texts in conversation with other faith traditions, particularly Senegalese Diola Religion. As a Poetics of Postcolonial Biblical Criticism, Negritude is an optic through which people of faith may look around themselves, critically reread their sacred texts, reassess their vocation, and practice mutuality with God and nature on the heels of chilling climate change. Enshrined in this innovative argument is a call for introspection and challenge for people of faith to assume their vocation--human participatory agency.

Frequently asked questions

Information

Introduction

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Figures and Tables

- Preface

- Abbreviations

- 1. Introduction

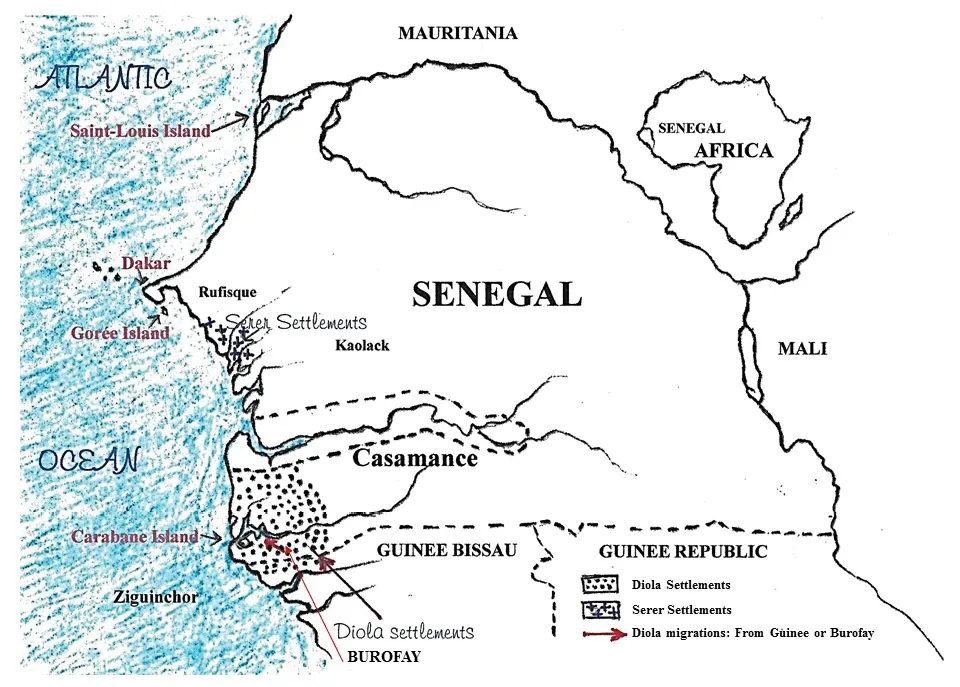

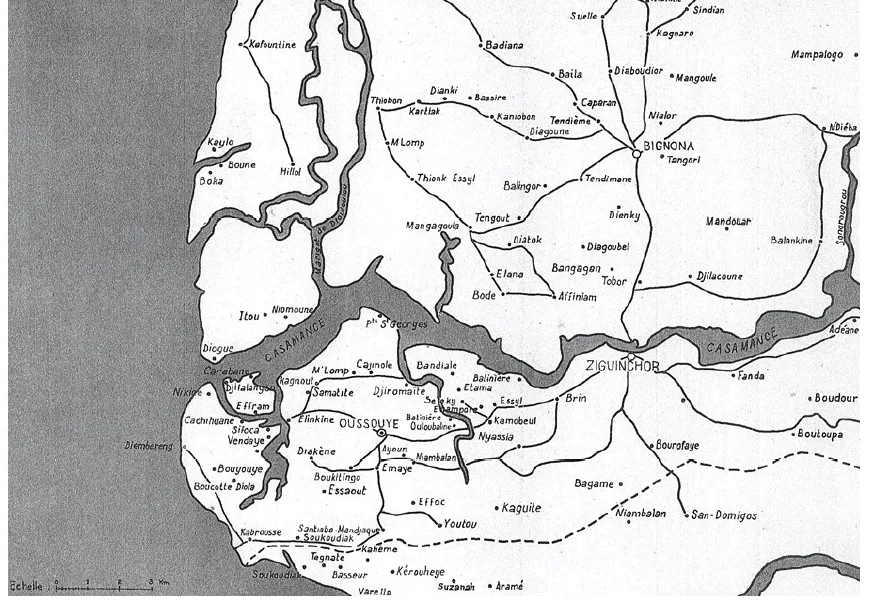

- 2. Human-Nature Relationship in Diola Contexts

- 3. The Divine–Human–Nature Relationship in Israel and Her Neighbors

- 4. Nonhuman-Human Relationship in the New Testament

- 5. Empire in Senegal West Africa

- 6. Conclusion

- Bibliography