eBook - ePub

Diving Deep Into Nonfiction, Grades 6-12

Transferable Tools for Reading ANY Nonfiction Text

This is a test

- 264 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Diving Deep Into Nonfiction, Grades 6-12

Transferable Tools for Reading ANY Nonfiction Text

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

All nonfiction is a conversation between writer and reader, an invitation to agree or disagree with compelling and often provocative ideas. With Diving Deep Into Nonfiction, Jeffrey Wilhelm and Michael Smith deliver a revolutionary teaching framework that helps students read well by noticing:

- Topics and the textual conversation

- Key details

- Varied nonfiction genres

- Text structure

The classroom-tested lessons include engaging short excerpts and teach students to be powerful readers who know both how authors signal what’s worth noticing in a text and how readers connect and make meaning of what they have noticed.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Diving Deep Into Nonfiction, Grades 6-12 by Jeffrey D. Wilhelm, Michael W. Smith in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1 Reader’s Rules of Notice

Reading is both our passion and our work.

We’ve dedicated our professional lives largely to the teaching of reading. But some time ago, we became aware that we’re considerably better at teaching students how to read literature than how to read complex nonfiction.

And when we recognized how many complex nonfiction texts we read each and every day and how much this reading contributes to the various kinds of formal and informal work we do—and to the various pleasures and passions we enjoy—it gave us a start. When we monitored our nonfiction reading in the context of our jobs, our lives as citizens, and our lives as parents, spouses, friends, and family members, we realized that if we were going to better prepare students for their lives both in school and out, we needed to focus our attention more closely on nonfiction and the ways that experts make meaning of such texts.

This book is our effort to do just that. In it, we share our understanding of what it takes to become a consciously competent reader of nonfiction, along with useful lessons that help students develop that competence and continue to develop expertise consciously over time. Our focus is on helping students learn and apply what we, following Peter Rabinowitz (1987), call reader’s rules of notice—that is, the cues in a text that help us recognize what authors expect us to attend to and then use to construct meaning.

What Skilled Readers Do

Our work is based on two central insights. The first is that reading is simultaneously a top-down and bottom-up process. The second is that not everything in a text is of equal importance. We address these one at a time in the following pages.

Expert Reading Is Simultaneously Top Down and Bottom Up

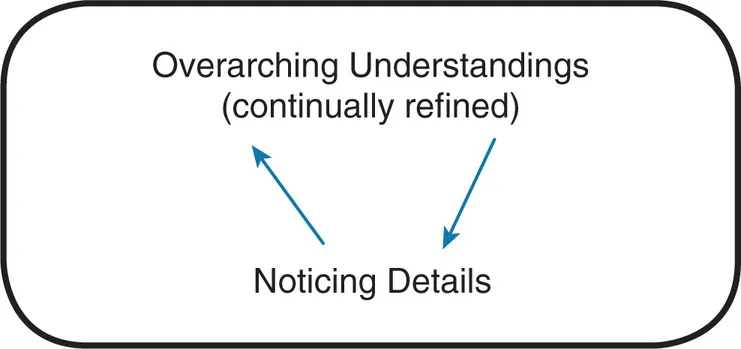

The first insight is that comprehending what we read is simultaneously a top-down and bottom-up process (see Figure 1.1). This may sound complicated, but it’s really quite simple: Expert readers start constructing an overarching understanding about the text as soon as they begin reading. This overarching understanding points them to the details they notice (top down), and these details, in turn, refine the overarching understanding (bottom up), which helps them recognize other details that lead to a further refined understanding (more top down), in a continuing process.

Figure 1.1 The Top-Down Bottom-Up Process of Reading Comprehension

As Kintsch (2005) explains, top-down processes “guide” comprehension, and bottom-up processes “constrain” it (p. 128). The influential reader-response theorist Louise Rosenblatt (1978) makes much the same point: As we read, we develop a “tentative framework” that influences the “selection and synthesis of further responses” (p. 54) that then reinforce or revise the framework.

We can illustrate this idea using the reading with which we begin our day: the newspaper. Michael subscribes to the New York Times, Jeff to the Idaho Statesman (or, as he’d prefer it to be called, the Idaho StatesPERSON). On the day we drafted this paragraph, the Supreme Court affirmed the right of same-sex couples to marry. We were both eager to read the reporting and commentary on this important issue. Michael began reading a Times editorial knowing it would endorse the decision and critique the dissenting justices’ opinions. Jeff was unsure what position the Statesman would take and looked for details revealing that position. Both of us read in ways that were mindful of the ongoing cultural and historical conversations about civil rights and the rights of same-sex couples, conversations of which the decision and newspapers’ reporting of it are a part. To guide us, we used our overarching understandings of the topic, the cultural conversation, and the kinds of texts (newspaper editorials, in this case) we chose to read to explore the issue.

Noticing the Conversation

This illustration reveals the importance of the schemas—which can be thought of as bookshelves in our brain—we use to store and organize information. Readers use background schemas to make sense of text. Reading research has long made clear the power of this schematic understanding.

Consider this short passage from a classic study by Bransford and Johnson (1972):

A newspaper is better than a magazine. A seashore is a better place than the street. At first it is better to run than to walk. You may have to try several times. It takes some skill but it’s easy to learn. Even young children can enjoy it. Once successful, complications are minimal. Birds seldom get too close. Rain, however, soaks in very fast. Too many people doing the same thing can also cause problems. One needs lots of room. If there are no complications, it can be very peaceful. A rock will serve as an anchor. If things break loose from it, however, you will not get a second chance. (p. 722)

Despite being composed of uncomplicated words, without schema markers to activate background knowledge, this paragraph was difficult for readers in the Bransford and Johnson study to understand. In contrast, readers who were told before they read that the topic of the passage was making and flying a kite had a much easier go of it—in fact, they experienced no comprehension problems whatsoever. That overarching conceptual understanding allowed them to activate their prior schematic knowledge about kites so they could use that knowledge to comprehend the text. Without activating that knowledge, even expert readers struggled mightily with the text. They couldn’t figure out the local-level meaning of words without some sense of the whole. The above passage is what textbooks and much complex nonfiction texts look like to students who lack or fail to apply the background knowledge that would help them make sense of their reading.

Experienced readers necessarily employ a priori conceptual understanding to aid in their reading of new texts. One reason we’re able to do so is because we tend to read to deepen existing areas of expertise rather than to develop entirely new ones. We know a lot about the cultural and historical conversations to which most of the texts we read are contributing. Our students don’t have that advantage in the reading they do in and for school. They don’t have schemas that are as well developed as those of adults; they have to read what’s assigned; and they are often learning about something totally new to them. Noticing the conversation a text is part of and activating or building the background knowledge necessary to comprehend that turn in the conversation are prerequisite steps to effective reading. This book therefore begins with lessons that help students notice the conversation a text is part of. If readers don’t notice this, they can’t activate whatever necessary background knowledge they have, and they can’t build new schematic knowledge about the topic that might be necessary to understand what is being said.

Noticing Key Details

Now, for the second central insight: Not everything in a text is of equal importance. Skilled readers know how to separate the wheat from the chaff; less accomplished readers have difficulty doing so. Reynolds (1992) provides a comprehensive review of research establishing that more successful readers self-consciously identify and pay more attention to important information than less successful readers do and that more successful readers continuously adapt their understanding of what’s most important as they read.

Noticing Genre and Text Structure

In addition to the a priori conceptual understanding we bring to our reading, we bring a priori understanding of how texts work. Let’s return to our newspaper example. We know that news stories have headlines but that these headlines are likely not written by the author of the story. We know that news stories, features, editorials, reviews, and so on all work a bit differently. We know that stories that appear above the fold are regarded as more important than stories on the same page that appear below the fold. We know that news stories are a genre and that this genre often employs text structures like comparison, definition, or process analysis. In short, we know how to notice both genres and the text structures embedded in those genres to guide our reading.

Peter Rabinowitz (Rabinowitz & Smith, 1998) applies a useful metaphor in thinking about genre and structure. He writes that reading a text is like putting together an item that arrives from the manufacturer unassembled—you have to have at least some sense of what it is you’re making (top down). You don’t just follow step-by-step directions without a clear sense of what you’re going to end up with. The steps only make sense if you know what the end product will look like. In that light, each individual piece needs to be understood in terms of how it connects to neighboring pieces and how everything contributes to the purpose and shape of the whole (bottom up).

What This Noticing Means for Us as Teachers

First, because understanding a text requires readers to approach that text with some general understanding both of the cultural and historical conversation of which it is a part and of its structural features and genre, we have to teach students to notice the way in which a particular turn in the conversation is framed and shaped. Fortunately, authors do specific things to help readers orient themselves to the conversation, the genre, and the text structures they employ. We have found that we need to teach students how to notice and attend to these orienting moves. If we do, students are much more able to enter into texts and make meaning of them. In fact, we have found that they do so with the enthusiasm and joy of a knowing insider, someone who is in the process of developing new forms of expertise.

Second, because skilled reading requires readers to notice key details—to sort out what’s important from what is less so—we have to teach students (1) to notice and use the signaling moves authors use to indicate what is most important and (2) to sort the important stuff they notice into categories that help them get a sense of the whole.

The lessons in this book are designed to teach students the rules of notice that expert readers employ, often unconsciously, as they read.

Principles of Effective Instruction

The lessons in this book are informed by four key principles.

1. The Importance of Teaching How

The first recommendation of the Reading Next report on adolescent literacy (Biancarosa & Snow, 2006) is that teachers ought to provide “direct, explicit comprehension instruction” (p. 4). Students need to understand how to do what we want them to do. This seems obvious, but many common instructional practices don’t provide explicit in...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Acknowledgements

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Videos

- Acknowledgments

- Chapter 1 Reader’s Rules of Notice

- Chapter 2 Noticing the Conversation

- Chapter 3 Noticing Key Details

- Chapter 4 Noticing Varied Nonfiction Genres

- Chapter 5 Noticing the Text Structures in Nonfiction Texts

- Chapter 6 Why This Method Works

- Appendix General Reader’s Rules of Notice for Nonfiction

- References

- Index

- Publisher Note