![]()

CHAPTER 1

PACIFIC ISLANDS LIFEWORLDS

There are three major cultural regions across the Pacific Islands, with a combined population of 10 million: the Polynesians of the Eastern Pacific (American Samoa, the Cook Islands, French Polynesia, Niue, Pitcairn Island, Samoa, Tokelau, Tonga, Tuvalu, and Wallis and Futuna); the Micronesians of the North Pacific (Federated States of Micronesia, Guam, Kiribati, the Marshall Islands, Nauru, the Northern Marianas, and Palau); and the Melanesians of the Southwest Pacific (Fiji, New Caledonia, Papua New Guinea, the Solomon Islands, and Vanuatu).1 Ancient Polynesian societies including Samoa, Tonga, and Hawaii, whilst far greater in number than ancient Melanesian societies to the west, were nevertheless constrained in size by island economies of scale, and the distances by sea between each. In Melanesia, where larger islands exist, the rugged physical environment constrained extended inter-ethnic contact and communication and resulted in patterns of conflict with close rather than distant neighbours (Rodman & Cooper, 1979).2 The only land border between states in the Pacific Islands is that between Papua New Guinea and Indonesia, with the remainder being maritime boundaries.

With exceptions, Pacific societies were led by chiefs and were patriarchal. Some Melanesian societies developed egalitarian relations in which any person of proven capacity could seek chiefly status. On the northern islands of Vanuatu, such as Pentecost, males achieve ‘grades’ through ritualised resource accumulation and distribution. In Polynesia, in contrast, hierarchically organised societies were divisible into noble and commoner families. Such societal attributes continue to affect the structure and operation of government at the present time.

Although some of the disparate peoples spread across these Pacific Islands operated complex traditional trade routes, it is only in comparatively recent times have they been brought together as states that share a common leadership and common system of government. There are now some 22 independent and dependent countries, which are referred to as ‘Pacific Island Countries’ (PICs for short). Many are archipelagos – clusters of islands which number in the thousands and on which an even larger number of distinct cultures and languages exist. And much of this ‘bringing together’ was without the peoples’ consent. Their contemporary territorial boundaries, systems of government, major economic partnerships, and political alignments (as described in more detail below) were imposed by one or other hegemonic power: England, Spain, Germany, Japan, Australia, France, USA, and New Zealand.

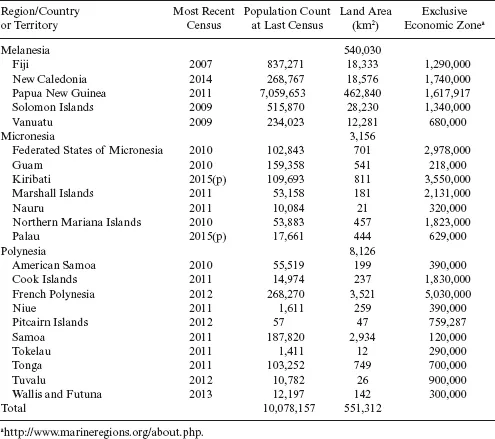

This is thus a study of the public sector in societies that identify as indigenous, which on the basis of their experience as formerly subject peoples hold in tension some reservations about international organisations, initiatives, and standards, on the one hand, and an acknowledgement of the benefits of acceptance and participation, on the other – sometimes amounting to a ‘cruel choice’ (Goulet, 1992, 1975). The populations and land size of these countries and territories are set out in Table 1.3

Table 1. PIC population, land and EEZ sizes

Of the 22 territories, 14 enjoy full national sovereignty and 10 have limited sovereignty or remain dependencies of a metropolitan power. Pitcairn, for instance, belongs to Great Britain; New Caledonia, French Polynesia, and Wallis and Futuna are overseas territories of France; American Samoa, Guam, and the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands are administered by the USA; and Cook Islands, Niue, Tokelau are freely associated states of New Zealand. This leaves just 12 PICs with sovereign status and voting rights in international organisations: Federated States of Micronesia, Fiji, Kiribati, Nauru, Palau, Papua New Guinea, the Republic of the Marshall Islands, Samoa, Solomon Islands, Tonga, Tuvalu, and Vanuatu.

1. LAND AND SEA

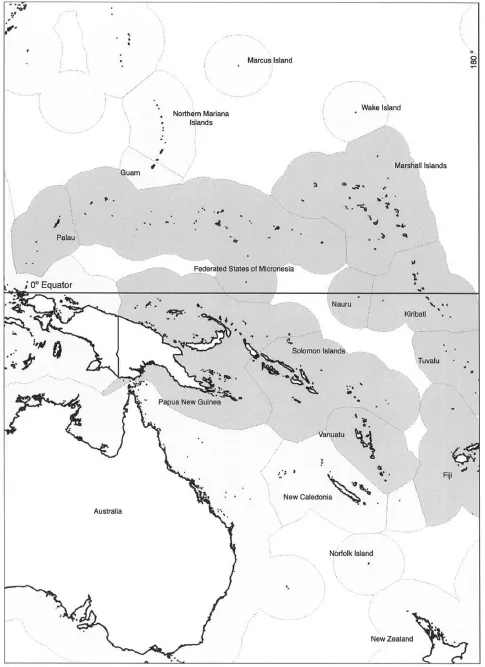

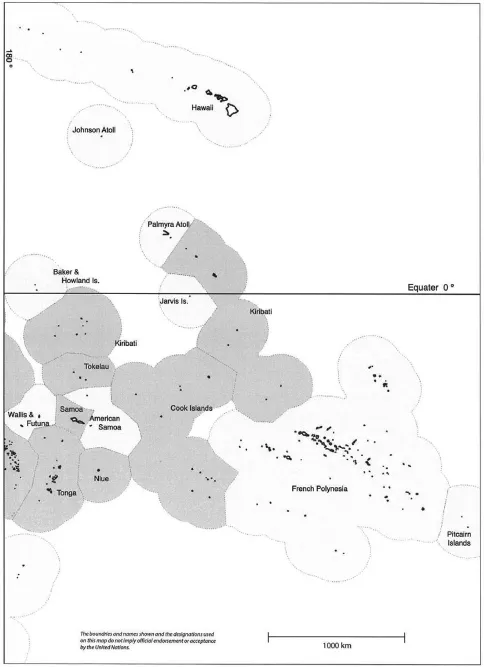

The Pacific Ocean has long been characterised by Western observers as a physical barrier, responsible for the remoteness of the small islands scattered across it, but is perceived by Pacific peoples as the means of connection. Contemporary leaders describe their countries as ‘Large Ocean’ rather than ‘Small Island’ states, and regional dialogue is undertaken under the banner of the ‘Blue Economy’. The Pacific Ocean is a traditional source of sustenance, and sailing upon it the main means of short as well as long-distance transport. Traditional inter-group trade was by sea rather than land, and marine resources continue to promise some of the best economic returns. For many PICs, income from the ocean’s resources is greater than that from land-based activities. Apart from the economic benefits from exploitation of the Ocean’s resources, the PICs value their role as stewards of an ocean which covers a third of the Earth’s surface, with a number establishing marine protected areas (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Pacific Island Country Exclusive Economic Zones (Continue)

1.1. Land

Scattered across the Pacific Ocean are some of the smallest of the world’s nation-states and territories, including the islands of Tokelau 26 (12 km2), Nauru (21 km2), and Tuvalu (26 km2). Ten additional countries have landmasses of between 199 km2 (American Samoa) and 3,521 km2 (French Polynesia). The other Micronesian states – notably Kiribati but also the Federated States of Micronesia, Palau, and Tuvalu – also comprise chains of islands, whose territorial waters are far more expansive than their landmasses. The landmasses of the five Melanesian states, although small by comparison globally, are nonetheless the largest in the Pacific, commencing with Vanuatu (12,281 km2), then Fiji (18,333 km2), New Caledonia (18,576), Solomon Islands (28,230), and largest of all, Papua New Guinea (462,840 km2).

Consider the impact of Pacific Islands’ geography on the structure and conduct of government: establishment of government authority and delivery of public services across islands is far more challenging than is the case on contiguous land. It is difficult to provide energy, schooling, and health services to all of a country’s citizens on an equitable basis. Provision on larger islands which may host the administrative and commercial centre and which are generally home to a majority of the population is one matter; but government is expected to provide similar standards of service to each additional island, irrespective of how small or how remote. In larger countries, these services might be established and maintained by road and rail, and even by air; but in Pacific Island context delivery often depends on sea transportation and in some situations on light aircraft. The hurdles to efficient and effective delivery of government services rapidly become evident.

Some Pacific Islands sit atop volcanic formations. Those include low-lying ‘coral cays’ as well as more mountainous formations. All PICs are subject to climate change, but those which are low-lying, such as Tokelau, Tuvalu, Kiribati, and the Marshall Islands, are far more vulnerable to sea-level rise than are islands in Melanesia. There are active volcanoes throughout the region, and earthquakes claim lives and property. Volcanic activity causes temporary disruption in some instances and permanent relocation in others. In Papua New Guinea the 1994 Mount Tavurvur eruption required evacuation of Rabaul, and in 2018 the people of Manam Island had to be evacuated due to the eruption of Manam volcano. Also, in 2018, the entire population of Ambae, in Vanuatu, required long-term resettlement due to volcanic eruption. The prevalence of such intense natural vulnerabilities means that disaster risk reduction is now mainstreamed in most PIC development plans.

The archipelagic nature of the Pacific Islands has resulted in the separate evolution of relatively small-scale societies and this has hindered expansion of national sentiments and aspirations.4 Pacific societies have dual identities through the distinctiveness of their individual cultures on the one hand, and the commonality of their circumstances on the other hand. The large number of islands, when combined with their small physical size, has been a primary influence on the creation of ethnic identity. The Marshall Islands, for instance, consists of two archipelagic chains of 30 atolls and 1,152 islands, with the majority of the population of approximately 50,000 concentrated on Majuro and Kwajalein atolls. Palau is a group of 200 islands in western Micronesia, of which just 8 are inhabited.

1.1.1. Customary Ownership

Colonial rule did not necessarily result in removal of lands from their traditional owners, who were more often a collective rather than an individual. The case of Tonga is unique inasmuch as the country’s land continues to be owned by the Monarch, and administered on the Monarch’s behalf by 33 Nobles, who allocate each adult male one urban and one rural allotment.5 In contemporary times the issue of ‘customary ownership’ divides those who value a continued sovereign relationship between people and their land, and those who believe it hinders economic development and advocate more privatisation. Land ownership and usage rights affects government decision-making across the Pacific, since the small amount of freehold land and popular resistance to efforts to acquire land through ‘eminent domain’ (i.e. compulsory acquisition by government for public purposes) means that government authorities often have to lease land for airports, harbours, and even entire urban areas (in the case of Port Moresby) in order to deliver the services expected by contemporary societies. Many current conflicts between people and government in PICs concern the terms agreed for land use.

1.2. Sea

The sea is more extensive than the land in all PICs, and in 2012, the Pacific leaders suggested in their 43rd joint communiqué that the islands be termed ‘Large Ocean Island States’ rather than ‘Small Island Developing States’ (Pacific Islands Forum, 2012). Each nation has rights to its foreshore, continental shelf, and exclusive economic zone (200 nautical miles from shore), beyond which are ‘international waters’. Collectively, they add to 550,000 km2 of land6 in 165 million km2 Pacific Ocean. Obviously, the more scattered a nation’s islands, the larger its jurisdiction over the ocean, and this helps to explain the motivation behind several sovereign disputes between Pacific countries over possession of far flung reefs and rocky outcrops: France and Vanuatu dispute sovereignty over Matthew (Umaenupne) and Hunter (Umaeneag) Islands between Vanuatu and New Caledonia; Manihiki Plateau is disputed between Tokelau and Cook Islands;7 and Tonga claims sovereignty over North and South Minerva Reefs (Teleki Tokelau and Teleki Tonga) which lie within 200 km of Fiji (Schofield, 2010).

Traditional exploitation of the sea for fish, and coasts and estuaries for other seafood from shellfish to seaweed, is still important to coastal peoples, whether for personal consumption or for sale. However, the harvesting of marine resources from coastal areas is threatened by such pressures as urbanisation, tourism, and climate change. Large-scale fishing has grown in significance. It contributes substantial revenues to national economies, but also drives much policy concerning monitoring and verification of catch-size and value, fishing vessel licencing, and marine conservation. The importance of marine resources to the well-being of Pacific societies meant that PICs engaged actively in development of the Law of the Sea, which articulates the ownership of each country’s continental shelf and exclusive economic zone.

1.2.1. Minerals

Scientific exploration of the seabed has identified mineral deposits, and Papua New Guinea is amongst the countries which have issued exploratory licences. In 2012, the Cook Islands established a Seabed Minerals Authority:

[…] to develop and mature the Seabed Minerals (SBM) sector of the Cook Islands in order to maximise the benefit of our national seabed minerals resources for the Cook Islands people and our investment and development partners, whilst also taking into account social and environmental considerations.8

Cook Islands EEZ is estimated to contain one-quarter of the world’s reserves of manganese nodules (Petterson & Tawake, 2019). Opinion on seabed mining is divided, however, on two main grounds: first a concern at the environmental impact, which is not well understood, whilst a second concern is economic, based on doubts as to whether the minerals are in sufficient quantities to be extracted profitably.

1.2.2. Climate Change and Sea-Level Rise

In the late twentieth century some Pacific communities began to experience sea-level rise, commencing with Papua New Guinea’s Carteret Islands and the low-lying islands of Kiribati, Tuvalu, and the Marshall Islands. Sea-level rise is not the only phenomena associated with climate change, as the islands are experiencing ever stronger and more frequent cyclones, such as those that have visited Solomon Islands, Niue, Vanuatu, Yap, and Fiji, in recent years. The risks and impacts of climate change are altering policy behaviour. They now occupy a central position in development planning and development financing, and in some cases are regarded as sovereign risk – risk, that is, to the exodus of populations through ‘climate migration’ and ultimately, to the very existence of peoples as sovereign nations (Connell, 2017).

2. PEOPLE AND CULTURE

2.1. Demographics

The Pacific includes some of the smallest human communities to be found anywhere on the planet. The British Crown colony of Pitcairn, which is governed by the High Commissioner in New Zealand, has a population under 100. Tokelau, which transferred from the Gilbert and Ellice Islands Colony into New Zealand administration in 1925 and remains a non-self-governing territory, has a population of some 2,000, administered by the local councils (Taupulega) of N...