![]()

Chapter 1

Making History

Darci L. Tucker, BA

Abstract

Professional storytelling and interpretive techniques can be successfully adapted for the classroom. For educators, character interpretation is an especially effective teaching tool. The author uses her extensive experience as an actress, storyteller, and educator to explain why character interpretation works so effectively to engage students and capture their attention. More than traditional methods of instruction, these established techniques put a “face” on history: They place people and events in a relatable, humanizing context that supports the teaching of controversial topics such as human rights and revolution. Using real-world examples, Tucker explains how character interpretation attracts people at all levels of ability and interest. Such presentations enable students to not only connect with historical figures' perspectives and motivations but also compare their own contemporary worldviews. Further, teachers can connect STEM education with history through their choice of people to portray, drawing from contemporary as well as historical figures to illustrate key learning concepts. This chapter outlines the educational value of framing a presentation within a socio/political/scientific context; doing so helps students to relate the presentation content to their own perceptions and to frame appropriate questions for the character if a Q&A takes place. The chapter further deconstructs the complexities of character interpretation into a series of manageable steps, explaining the sequence of storytelling from character conception to performance. Guiding questions at the end provide useful suggestions for dramatic presentations by teachers and students.

Keywords: Character; interpretation; storytelling; first person; third person; museum

To say that I believe in character interpretation as a teaching technique is an understatement. I am passionate about it. I know that it works. I know it not from scientific statistical analysis, but from more than 25 years of experience. I have watched audience members laugh, cry, and on at least two occasions shout abusively at the characters I was portraying. While that was not pleasant, it speaks to the power of the technique. Those people were so drawn in that they momentarily forgot that I was acting, and that the person they were angry with had been dead for more than 200 years. Let me assure you, at this point, that I am not a trained actor. I took three semesters of drama in high school, where my big moment was an offstage scream. I took one semester in junior college that consisted of stage exercises. Good character interpretation does not require acting lessons. It requires imagination. It requires the ability to put yourself into someone else's shoes and imagine how they felt.

I have always loved history. I fell in love with it on a trip to the Henry Ford Museum when I was tiny. That love grew as I read Laura Ingalls Wilders' books about growing up on the American frontier. I heard the panther screaming in the treetops as it chased Pa. I fought the prairie fire and felt the snow on my bed and listened to the wolves howling far too close. I wanted to be Laura.

When I was in college we took a family vacation to Williamsburg, Virginia, and Colonial Williamsburg, the world's largest living history museum. I encountered, for the first time, people whose job was to “be” people of the past. What a revelation! After graduating from UCLA, I moved to Virginia to work at the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. Since they were not hiring character interpreters at that moment, I became a third-person interpreter, telling about the past instead of portraying it. Several years later, I was cast in the reenactment of a court trial that was partly scripted and part improvisation. The director, impressed at my historical improvisation abilities, suggested me for the role of the Royal Governor's wife, Lady Dunmore. It was a part-time occasional role, but I had jumped from dreaming about doing character interpretation to having one of the most luscious roles at Colonial Williamsburg (Fig. 1.1).

Fig. 1.1. Darci Tucker as Charlotte Murray, 4th Countess of Dunmore. Credit: Amanda Jones.

In 2001, I left full-time employment at Colonial Williamsburg and wrote a one-woman, three-character interactive play about the American Revolution entitled Revolutionary Women. This play is part scripted and part improvisation. I have spent the past 19 years performing it in schools and other venues all over the country. I have also spent those years doing teacher workshops, showing teachers how to portray people of the past, and how to teach their students how to do the same. I even wrote a how-to book, entitled Embodying the Story through Character Interpretation: A Step-By-Step Guide to Being Someone You Aren't.

Further, each time a potential customer has said “Well, I'd really like you to portray this character, instead,” I have created that character. I have portrayed more than 20 different women from three centuries of American history. I have devoted months of research to some, to portray them only once. But about 10 have become regular parts of my repertoire. My characters range from a 1750s indentured servant to twentieth century aviator Amelia Earhart. And I seem, always, to be working on another.

Why? Well, to quote Amelia Earhart from her autobiography title, I do all this for “the fun of it” (Earhart, 1932). Every time I hear about an interesting woman I think “Oh! I'd love to portray her, too!” It's intellectually stimulating. I learn so much through the process of creating each character. I know things about our national history I would never have known otherwise. In search of their experiences, I have visited many of the places those women lived. My life is so much richer because of their lives. And besides, I get to play dress-up for a living!

But more importantly, I do it because I long ago realized that I was put on earth to help kids see that history is not boring. Every time I visit a school I know that there will be kids who walk into my program thinking “I hate history.” My job and my passion is to make sure that at least one of them walks out thinking “That wasn't so bad.” Because if they think, “That wasn't so bad,” they may pick up a book or go online to find out more. And a whole new world may open up for them.

This book is a collection of articles about how and why character interpretation is an effective classroom technique. It is written by classroom teachers, college professors, and museum educators, and they approach the topic from a variety of angles. Some have portrayed historical people. Others have taught their students to portray historical people.

I am excited to work with so many talented friends who have also discovered the effectiveness of teaching through character interpretation. In this chapter, I focus on character interpretation's strengths and pitfalls and on why I think it is one of the most effective ways to teach. I will leave it to my colleagues to tell you their processes. There are lots of different approaches, so I hope you will find one that works for you.

What Character Interpretation Does

I am not a classroom teacher. Several other authors in this book are. They can tell you more about the power of character interpretation in the classroom than I can because they see its long-term impact on their students. What I can tell you is that teachers invite me back year after year. Some say they could not teach the American Revolution without my presentation, which I think speaks to the effectiveness of character interpretation.

It Works Where Other Techniques Often Fail

In the past 20 years, I have performed in hundreds of schools, for tens of thousands of students. Character interpretation works for students regardless of their academic ability. I believe it taps into a different part of the brain. Anyone who can listen to someone else's story can benefit, even if they have learning disabilities or are not interested in the topic.

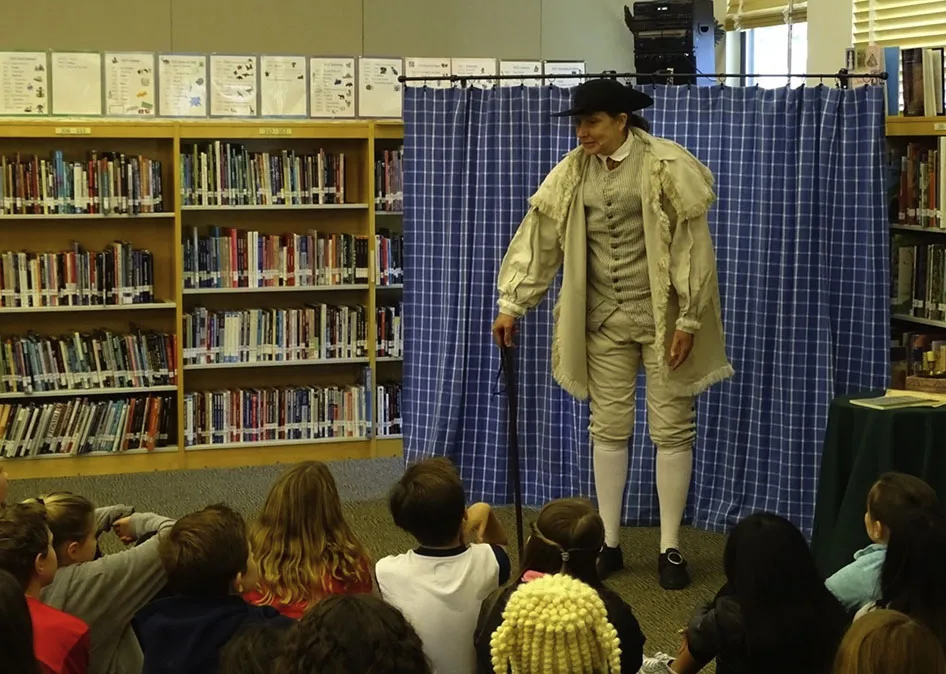

Over and over teachers have told me that they held their breath when I called on “little Sylvia” and were pleasantly surprised that her question was so relevant. They have told me that “Terry,” the one who had so many questions, never talks in class – or that “Sam,” who answered the question I posed, is a student with autism (Fig. 1.2).

Fig. 1.2. Darci Tucker Portraying Deborah Sampson, Who Disguised Herself as a Man to Enlist and Fight in the American Revolution. Credit: Jennifer Sterling.

I know that the students retain an astounding amount of information. Two hours after Revolutionary Women ends, if I ask how far Deborah Samson walked to enlist in the army, students shout, “35 miles!” I receive student letters that demonstrate how much content they retained from the performance, and their illustrations show how vividly they imagined the scenes I described. One fifth grader emailed me with questions for months after my presentation. An eighth grader, embarrassed by his own interest, sidled past me mumbling, “I hate to admit it, but that was really kind of awesome.”

Maybe the novelty of the approach catches their attention. Maybe it is because the person teaching is not giving an “I know more than you do” lecture. Maybe it is because the facts are woven into a story that matters to the students because the event happened to the “real person” in front of them. Maybe by meeting that “real person,” students are able to imagine themselves in a similar situation, and those moments of imagination make the information stick.

It Humanizes Difficult and Controversial Issues and Events

Students are often better able to see different perspectives after a first-person interpretation. As the old sayings go, “The winners write the history books,” and “You don't really know what you believe unless you know the arguments against it.” First-person interpretation can be a very effective way to help students understand the views and motivations of people on the losing side of history, by illuminating what they believed and why. Sometimes those people were on the wrong side of an issue, but more often they were merely on the side that did not win.

In Revolutionary Women, I portray a loyalist, a patriot, and someone who is undecided. Teachers often tell me that their students all entered the room thinking they could have been patriots, but after the program a fair number of them left thinking they could have been loyalists, instead. Hearing the loyalist perspective from a “real person who lived it” made them open-minded enough to consider views they had discounted before. They no longer saw good guys and bad guys; they saw individuals who faced very difficult decisions. They imagined themselves doing the same.

My friends Sheila Arnold and Valarie Holmes, contributors to this book, portray African Americans during the slavery and civil rights eras. I have watched their audiences sit spellbound, with tears in their eyes as they listened. I have heard numerous people say, “I never really imagined what that was like before now.” I have watched tearful teachers hug Sheila and Valarie and thank them for telling the stories of their own (the teachers') families, stories that had been kept silent in many cases. What power to help people find themselves in our American story!

Similarly, years ago, Colonial Williamsburg interpreter Kristin Spivey portrayed Annabelle Powell at that museum. I took every school group I could to meet Mrs. Powell. She was warm, kind, intelligent, and funny. The kids fell in love with her. Then she would reveal, very unapologetically, that she owned slaves. The students would almost flinch because it was so hard to believe that someone so kind could matter-of-factly participate in an institution as cruel as slavery. What an important lesson to them about the complexities of human nature; that we are products of our own time and often do not question the values with which we were raised; that we generally put our own needs and desires above those of others; and that if we had been raised as Mrs. Powell was, we might have thought slavery was alright, too.

Character interpretation, at its best, makes the audience think about their own values and actions. Hopefully, it helps them see that people of the past were just people. Someday people may look back at us and believe that we were on the wrong side of history, and it may be for something we cannot currently imagine is wrong.

It Can Clarify Processes

Character interpretation gives liberal arts-minded students a door to approach STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Technology) subjects. For example, I have absolutely no interest in math and very little aptitude for it. My friend Willie Balderson portrays an eighteenth century surveyo...