![]()

1

Symbolic Narratives as Told by Ghosts and Bones

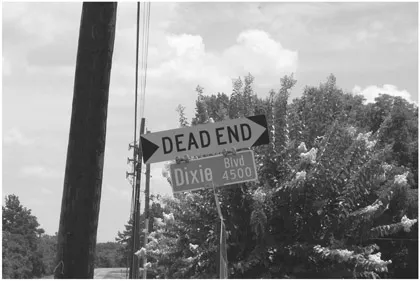

Situating Race, Place, and a Beginning Story Gone Bad in the Deep South

“[White, Southern man] boasts of the purity of his Anglo-Saxon blood—and, sub rosa, winks at miscegenation. Yet, he is never—consciously, at least—a hypocrite. He is a Tartarin, not a Tartuffe. Whatever pleases him, he counts as real. Whatever does not please him, he holds as non-existential.”

(Cash, 1929, p. 186)

“The embedded temporality of a place helps define it. Place is place only if accompanied by a history.”

(Kincheloe and Pinar, 1991, p. 8)

“The Southern mind has always been divided between pride and piety.”

(Wyatt-Brown, 2001, p. 83)

37 The hand of the Lord was upon me, and carried me out in the spirit of the Lord, and set me down in the midst of the valley which was full of bones …

5 Thus saith the Lord God unto these bones; Behold, I will cause breath to enter into you, and ye shall live: …

10 So I prophesied as he commanded me, and the breath came into them, and they lived, and stood up upon their feet, an exceeding great army.

(Ezekiel 37, KJV)

Living the past is easy. After all, it is always with me and whispers “the old ways are the best ways.” The past loves for me to tell its stories, tales that satisfy its hunger for immortality and relevance. So I acquiesce, but not in the way the past intends. My narratives are from a long line of hardened, grimly determined Scotch-Irish folk with a family tree planted in the North Louisiana soil, roots stretching past the facts of history and into the mist of cattle and sharecropper lore. Family ghosts visit my slumber and cast their watchful shadows in the morning. Since my birth in 1963, these Southern revenants have taught me who I am and who I can and cannot be. Their stories ground me. But they also burden me with tales of tradition, of a Southern man’s honor and glory in defending family and the places called home against those who would take away our land. They comfort and counsel when doubt about the moral and ethical value of the past I have inherited disturbs my sleep. How do I now repay them? I betray their trust. I question their veracity. So they turn mean and defiant.

Unfortunately and fortunately, that is the cost of the moral imperative to interrogate the spirits animating my North Louisiana existence and possible identities, especially when these ghosts darken the narrative with racialized fear and desire. And when my ghosts refuse to acknowledge the raw history of my home, I am left with no choice but to return to my place and plow the graves holding the bones buried long ago, waiting for a chance to tell a story not so honorable. This is a dangerous and often humiliating business. But Ezekiel’s proclamation rings true: give breath to them bones. Crack open the coffin lid and my ancestors’ skeletons spill out like a great army that marshals words I do not want to hear but cannot silence. The bones ridicule the chattering spirits’ stories of honor in poverty and pride in a willingness to suffer hardship generation after generation in the name of their God, the Almighty of the King James Version of the Bible that my tribe believed chose them to be the salt of the earth and who worked to make His garden grow and pass on lovely tales to keep the memory of the Lost Cause among the living. But, the bones also speak of flawed, hardened, impoverished, ravaged, and prideful people who desperately held onto a metaphor that always promised something better, in either this world or the next because of their whiteness. Yet, they shared more with those they were taught to fear and hate—blacks who lived just one rung down on the mudsill—than with the top of the Deep South racial hierarchal ladder they were told to admire and emulate. They failed to understand the possibility and promise of what solidarity with their black brethren could bring because race and their religion blinded them.

The bones tell stories of my tribe, quick to drink to excess, quick to laugh too hard and to fight when their hackles were raised by the softest of slights, quick to fumble over words to express the despair of existing in the Deep South with rage and balled-up fists ready to strike against anyone not of our tribe, or for that matter family and friends, if enough whiskey or moonshine has been consumed. This is history written in lightening and just about as deadly. All of this because of a blind devotion to ghosts who pledged glory and gardens and a grand role in the Lost Cause but delivered only dirt to my family, along with the occasional scrawny chicken to chew on and brim from the pond. These are sad and brutal stories. And they are racialized to the core. But do not dismiss them too quickly nor judge them too harshly. They are raw, honest, and solid and the bones need to tell them in order to silence the ghosts.

At first, my ghosts try to defy and refute these bones. How I loved their lies. But the bones speak hard truths about my tribe’s place. Justice will not brook otherwise. Places have histories written in hunger and thirst; they reveal an appetite for blood and excluding other possible ways of being. These tales follow the sons and daughters of a place like shadows extending to a beginning point in which the purpose was clear but somehow vanished, except for a sensation that every word and deed stubbornly attempts to recreate. In the Deep South, place hides its past in plain view by cultivating within each body a romanticized, pastoral story in which one’s white inheritance is the gift of a sacred white mythology that protects its boundaries from all possible invading narratives. Kincheloe and Pinar (1991) assert that when excavated, a place’s past and the stories folded within the bodies of its inhabitants reveal “an epistemology of place” (p. 10). Such knowledge changes my sense of place. It changes the tenor and timbre of my ghosts. Kincheloe and Pinar (1991) emphasize that one’s place must be “turned inside out” to expose the lies and promises of ghosts. Only then can one be granted “insight into the human condition, historical movement and/or anthropological expression” (p. 7). For those anchored in the ways of the Deep South, this existential-hermeneutic excavation is a transgression of sacred boundaries that could easily turn into an autopsy. Such is the risk every Southerner, black or white, must take. A moral imperative is to capture these seductive revenants and force them to disclose the underbelly of those wonderful and terrible lies of why and how the primal Southerners’ passions to build something beautiful from the hot and wild forest, sliced through with rivers and lakes, was twisted into a dark but profitable impulse to enslave African men and women. It took a handful of Anglo men with the right kind of tools and resources and Bible verses to justify the holiness of their acts as necessary to make this place God’s Garden. I guess what my Sunday school teacher taught me was true: Lucifer knows his Bible verses well and twists them to seduce us and expose our frailties.

This original spirit was supposed to be an Agrarian ideal, a promise to all individuals of a place in a special Garden as long as, and if, they were willing to farm and conserve the land through hard work and faith. But an existential choice, always an act of violent exclusion, cleaved Africans from this pledge, deeming them unworthy of earthly rewards for their labor. My boyhood home along the Red River in North Louisiana is a visual history of how this dream formed a deep and abiding attachment to the soil that failed to stay sacred. Instead, Anglo-European hubris made the ideal unrecognizable by lashing it to a dreadful and peculiar institution we know as slavery. Wealthy, land-owning Anglos certainly built a garden with the hard labor of indentured whites and enslaved Africans, and it quickly turned ugly. It was the white Southerner’s original sin. It broke our souls and we went mad, cursed with a spiritual sickness infecting all who steal from another human the natural right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. From the shreds of this sin came rationalizations, biblical and biological explanations, fears, lust, hate, shame and intimacy, all brewing into narratives of racialized existence, each story lived a little differently the deeper a family settled below the Mason-Dixon line. However, common to each place was the metaphor of a Garden that never was, and a nightmare of a Lost Cause that should have never been. Over generations, these stories of one’s place settled into a kind of rhythm, a mythopoetic verse and repetition of Anglo tropes of tradition, honor, family, individualism, God, and freedom in all its vagaries and vagueness. White Southerners woke up one day and forgot they were dreaming and assumed the stories to be real. We believed and lived out their principles, showing fealty by passing them on to each new child.

We have had chances to wake up and speak differently. Each time, in that pause before our impulses formed into words, there was a space of possibility within which all Southerners could realize a shared inheritance of the passion and vision and values of an agrarian society in which black and white families tilled the land with hands blackened by soil rather than by melatonin or the blood of another race, all in an effort to cultivate something sacred and worth preserving.1 But those words never came. Instead, Southern whites swallowed whole a lie crafted by the planter elite and the political scribes who served them to safeguard their own wealth and prosperity. Their words and deeds created our ghosts: You may be poor and uneducated but God bestowed upon you a special present that will act as a kind of property, a valuable currency in the political, social, and economic existence of the South. The gift was whiteness, and while they were not under threat of slavery as black Southerners were, their servitude continued under the heavy thumb of planters and politicians and the self-delusions created by the narratives of their place. My forebears ate the apple and saw that they were white. Yet, instead of shame they felt pride. They accepted the tale granting them the status of true Southerner, effectively silencing the voices of black slaves in the official story, and refusing blacks the right to pursue their happiness farming their own plots of Southern land. This past, those ghosts, still refuse to relent.

Reconstruction delivered to white Southerners a gift in defeat, a chance to ask forgiveness for the original sin, to reconcile with their black brethren and together remember the shared connection to the land. But white Southerners turned away, looked homeward to their ghosts and blamed blacks for refusing to stay enslaved. Southern whites devised a political insurrection to re-capture control of state and local institutions. Jim Crow made its stand, and when the Civil Rights movement chipped away at Crow’s feet, the past paused and the future held its breath, waiting to see if my parents’ generation would refuse or welcome the ghosts to re-inscribe the past upon my soul in 1963. An interstitial space opened to discuss and reshape the inherited symbolic narrative of what it meant to be a black or white Southerner. It was a “Come to Jesus” moment for both black and white Southerners to address each other with the stories of their lived experiences, to reveal the shared suffering that both endured but of which only whites were allowed to speak. These stories could have become a complicated conversation. Such an address would have forced the unreconstructed ghosts into a clearing to confess their sins and excise their ridiculous assertions of racial purity and denial of miscegenation as the standard rather than a deviation (an act of deviance). As one research study on DNA showed, white Southerners are likely to have more black DNA than any other whites in the United States (Varandani, 2014). No matter how white or black one’s skin, the blood of each flows within the other in the Deep South. Despite the loud decrees that one was of the white race, with its firm attachments of conservatism and a patriotic religiosity, purity did not nor could not exist in the Deep South. In fact, this delusion was so deeply rooted that it was codified in the early 1900s through the one-drop rule, a desperate state law of the Jim Crow era that somehow managed to stay on the Louisiana books until 1985. The most famous of Louisiana governors derided such a racialized dream even as he employed cynical race baiting tactics to win state elections. Huey P. Long, governor in the late 1920s, was heard to remark, “You could feed all the ‘pure whites’ in Louisiana with a nickel’s worth of red beans and a dime’s worth of rice” (quoted in Fairclough, 1995, p. vii). Such an acknowledgment never found a way into a conversation. Instead, pride filled the space and the moment passed. We gave into the ghosts. White Southerners dug in their heels and grew stubborn in defense of a delusional past, and loudly sang a song of innocence in the present. Our spiritual sickness weakened any resolve to stay civil. We handed our ghosts the power to turn into something terrible, apparitions made flesh and full of rage and ready to set the cross aflame to burn bright again. Time failed to completely douse the racial fires. Embers would flare, sometimes as rage, sometimes as worship, sometimes both. In summer 2015, that first terrible spirit was rekindled when a young white man struck a match in Charleston, South Carolina, and charred the landscape with black bodies, signaling the return of the Southern white man’s madness over his original sin. It was a bloody summer.

† † † †

June 17, 2015, early evening. Dylann Storm Roof acted out what William Faulkner (1961) had placed in the mouth of Gavin Stevens in Requiem for a Nun: “The past is not dead. It is not even past.” With a handgun, Roof shot a symbolic message in blood on the bodies of 10 African-Americans at the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina. He wore the cloak of a Southern Christian as he executed nine African-Americans kneeling, heads down in prayer to a God given to them 400 years before by the very white men who “owned” their ancestors. The old spirits whispered that Roof’s pain was not his fault, but the fault of those who would not stay subservient He had succumbed to the ghosts and their stories without hesitation.

Roof had become increasingly angry that “blacks were taking over the world” and were the cause of all his suffering (Silverstein, 2015). His gun was wielded to express what many whites felt but feared to vocalize—the South was becoming black, whiteness had lost its way. Instead of speaking under a church steeple, he built his own virtual chapel, a website where he worshipped the myth of the Lost Cause by holding a gun to his chest and draping himself in a Confederate flag. He even published a white supremacist manifesto that read as if pulled directly from nineteenth and early twentieth century Louisiana newspaper editorials or popular Old South novels. Roof dreamed of martyrdom for the recovery of the white man’s rightful claim to the land, to the dream. He believed that the moment the chains came off a race war was inevitable. He had embodied the inherited mythos that rose from the post-Reconstruction era in which defeat by the North became a trial by God. That is not a little white lie, but a full-blown white fantasy to mask a fractured psyche caused by the Deep South’s original sin of slavery, a condition that worsened once the slaves were freed and Reconstruction brought further humiliation to the pride of the Southern white. In an effort to restore pride (such a terrible sin) and make sense of their crumbling world, literary and historically minded white Southerners quickly penned a new narrative that retained the racialized tropes but read more as a lament than a promise:

The South afflicted with the curse of slavery—a curse like that of Original Sin, for which no single person is responsible—had to be destroyed, the good along with the evil. The old order had a great deal of good, one of the ‘goods’ being a result of the evil; for slavery itself entailed a certain moral responsibility which the capitalist employer in free society did not need to exercise if it was not his will to do so. This older order, in which the good could not be saved from the bad, was replaced by a new order, which in many ways was worse than the old. The Negro, legally free, was not prepared for freedom; nobody was trying to prepare him. The carpet-baggers… and ‘scalawags’ gave the Old South its final agonies… The Evil of slavery was twofold, for the ‘peculiar institution’ not only used human beings for a purpose for which God had not intended them; it made it possible for the white man to misuse and exploit nature for his own power and glory.

(Tate, 1975, p. 151)

Unlike the theocratic Colonial Puritan dream of a “city upon the hill,” which dispersed into jeremiadic cries of declension and a penchant for capitalism (Miller, 1957), the white Southerner quickly recalibrated his agrarian myth into a “dramatic projection of heroic action, or of the tragic failure of heroic actions, upon the reality of the common life of a society, so that the myth is reality from within, in the South the aim to create a Greek like society” (Tate, 1975, p. 151). No matter the damage done, the white man had to protect a plain and simple belief in his whiteness as something special. Roof feared this was a battle they were losing.

Roof comes from a long line of South Carolina families. As such, Roof is not an abstract thinker. He is an unreconstructed Southern literalist who listened intently to the ghosts who told him not to reflect on his troubled soul but instead focus on the black faces that made him angry. He went old school South. He discarded the polite, implicit, systemic institutional racism and denial that has prevailed in the New South since the 1970s. Instead, he embraced the ghosts of revenge. His murder of those African-Americans was, I believe, inevitable following years of young unarmed black men killed (murdered?) by police officers, or those who assumed the role of law enforcement and hid behind state laws such as “Stand Your Ground,” made famous in the Trayvon Martin case in Florida, a case about which Roof obsessed.

With each incident, a majority of whites hid behind claims of “due process,” declaring that accused officers were investigated and found to have acted in accordance with laws and policy. Apparently, it is legal for a police officer in Ferguson, Missouri, to confront an unarmed young black man fleeing out of fear and shoot him more than a dozen times through a car windshield, leaving the coroner unable to determine which shot killed the young man. The officer argued that he feared for his life. Google the phrase “unarmed black male killed” and the result is overwhelming and distressing. When protestors took to the streets in Ferguson to express their grief and outrage and plead for a change that would coalesce into the “Black Lives Matter” movement, police stationed newly acquired, shiny and brash military armor, weapons and vehicles that took aim at the crowd, a stark visual reminder of Russian tanks rolling into the center of Prague to squash the Spring of 1968 Peace and Freedom movement. How did white America respond to the many a...