![]()

Part I

Theories and Frameworks

![]()

1 Introduction to Politics, Media and Democracy in Australia

The central role of the journalistic media in the construction of an informed citizenry and deliberative democracy is widely accepted in the political science and media studies literature (Habermas, 2006; Davis, 2010; Louw, 2010; Cushion 2012a; Albaek et al., 2014). The liberal media’s functions of reportage, analysis, commentary, representation and advocacy (McNair, 2000) are recognized to underpin genuinely democratic political systems by informing citizens about the issues on which they have the constitutional right to exercise political choices (through voting, for example, and other forms of civic engagement and participation), supporting critical scrutiny of political and other elites in their exercise of power, and providing expression to popular and other forms of opposition to established authority. “Sound political knowledge”, assert Albaek et al., “is vital to the good health of a democracy” (2014, p. 95). Habermas defines democracy as “the inclusion of free and equal citizens in the political community” (2006, p. 412), and in relation to the importance of political media has observed that “the deliberative model of democracy claims an epistemic dimension for the democratic procedures of legitimation” (ibid., p. 411). In other words, public access to accurate and timely knowledge about political issues is crucial to the construction and maintenance of a democratic culture.

For that reason political actors, interested publics and scholars of media and politics have long been concerned with the performance of the media as democratic supports and resources. And they have long been critical of that performance. More than two decades ago Blumler and Gurevitch identified a Crisis of Public Communication (1995) in liberal democracies, arising in large part from perceived flaws in the political media’s performance of its normative role. Media and political science scholarship – in Australia and internationally – has been highly critical of the media–politics interaction ever since (Franklin, 2004; Young, 2011; Aalberg & Curran, eds., 2011). Indeed, in all the major democracies since the arrival of universal suffrage and mass media in the early twentieth century there has been more or less continual public debate about how the political media should perform their allotted democratic functions.

Critics have focused on perceived threats to integrity of the public sphere such as the growth of public relations in the twentieth century (Habermas, 1989; Davis, 2010), ideological bias arising from excessive concentration in the ownership structures of Big Media (McChesney, 2015) and the ‘dumbing down’ of political media content (Temple, 2006), as tendencies towards more populist, less ‘serious’ forms of political media content are often characterized.1 All of this is extensively referenced in the political science and media studies literatures, and often linked to a perceived crisis of democratic disengagement or non-participation as reflected in declining voter turnouts and other indicators. While we in previous work have critiqued the crisis paradigm and its associated narratives of decline (McNair, 2000; Harrington, 2012a), it is fair to say that they have dominated the field of political media studies throughout the liberal democratic world since at least Blumler and Gurevitch’s 1995 book.

The rise of the internet has, however, transformed the media environment in which these arguments were once framed (although their validity was also contested before the internet became a mass medium). The analogue age of top-down, centralized, industrial-scale media outlets dominated by a few barons and corporations, and distributing dysfunctional content (from the point of view of what is presumed to be good for democracy) has been disrupted and transformed by an explosion of sources of information and opinion which never previously had access to or visibility in the public sphere. As we discuss below, the public sphere, whatever its limitations as a discursive democratic platform in the past, has become networked, globalized, digitized and more participatory than has ever been the case, generating more critical scholarly recognition of what Des Freedman has termed The Contradictions of Media Power (2014).2 The default position of critical media scholarship on this topic – cultural pessimism, in so far as the trends in political media have been evaluated as negative – has become subject to more contestation as the internet has evolved. The field has demonstrated growing recognition of the complexity of the media–politics–democracy interaction, and the inadequacy of what we have previously termed the control paradigm (McNair, 1998, 2006, 2016b) in coming to a fully nuanced understanding of the media–power–politics relationship in contemporary conditions.

Even as the media in Australia and comparable democracies have expanded dramatically in recent times with the growth of digital and online platforms which have both increased the number of sources of political information available to citizens, and enhanced opportunities for public participation in mediated political debate, concerns about the functionality of the politics–media relationship remain high on the public agenda. There continues to be a perception amongst many political actors, media practitioners and members of democratically enabled publics in Australia (in so far as the latter’s views on trust and other media-related matters are known from the findings of opinion surveys) that much of the cynicism and disillusionment Australians reportedly feel towards politicians and political processes is related to the way in which politics is covered in news, current affairs and other media formats. The findings of the Finkelstein Inquiry Into the Media and Media Regulation,3 set up in the wake of the phone-hacking scandal which engulfed News Corporation in the UK in 2011, found for example “significant concerns in the minds of the public over media performance”. On the issue of trust, the inquiry found that the level of public confidence in journalists as a professional group and the media as institutions was lower than for almost all other professions and institutions (only real estate agents, advertising people and car salesmen ranked lower).4 The Reuters Digital News Report of 2015 similarly found that Australians expressed relatively low levels of trust in their news media (Newman et al., 2015).5 The News & Media Research Centre’s Digital News Report 2016 found that only 32.2 per cent of respondents in a survey of 2000 trusted journalists, and only 43.4 per cent trusted news in general (Watkins et al., 2016: 61). Freedman cites earlier Essential Media research which showed that around one third of Australians surveyed viewed the media as “extremely corrupt”, and that 20 per cent had “no trust” in the Australian media (2014).6 A UK focus group study in 2008 found that “public trust collapses when journalists are perceived to be reporting on social groups, areas and practices that they do not understand. Distrust happens when the news fails to address the world as the public recognise it, leaving them feeling like outsiders looking on at a drama that even the leading performers do not care if they really comprehend” (Coleman et al., 2009: 2).

Somewhat more reassuringly from the perspective of practitioners, Finkelstein reported that the Australian public was generally more satisfied with media performance than dissatisfied. On the other hand, a 2011 survey by Essential Media found only 35 per cent of respondents agreeing that “the media usually report the news accurately”. This was a sharp decrease from a 1990 survey by Saulwick which found 76 per cent of respondents believing that television presented news accurately, while 50 per said the same of newspapers. Finkelstein highlighted similar findings on perceptions of how well the Australian media perform their public watchdog role, with two surveys showing fewer than half of respondents agreeing with the statement that the Australian media performed well in this capacity.

On media bias and how it compares with levels of “fairness, diversity of opinion and balance” in Australian journalism, Finkelstein observed “a widely-held public view that, despite industry-developed codes of practice that state this, the reporting of news is not fair, accurate and balanced”. The review found, unsurprisingly given their privately owned status, that bias is much more commonly perceived to exist in the content of newspapers than in television or radio. Essential Media’s 2011 survey found that 21 per cent of respondents agreed with the statement that the media usually report all sides of a story, while 69 per cent disagreed.

During the Finkelstein inquiry’s public hearings, editors and executives from News Ltd., Fairfax, and Seven West Media claimed not to perceive any problems with “the integrity, accuracy, bias or conduct of the media” (Greg Hywood, CEO of Fairfax Media, quoted in Finkelstein, 2012: 103), defending their adherence to high press standards with reference to their readers as “rational truth seekers”, and arguing that the marketplace is the ultimate mechanism of accountability. An editorial in The Australian around this time claimed that “in the commercial media, our relevance is measured every day by our readers. If you do not appreciate or trust us, you will shun us. Our very existence hinges on being germane and responsive to the interests and views of our readers.”7

In Australia, as in the UK and comparable democracies, perceptions of bias are often part of the political debate itself, and usually bound up with the political divide in parliament (which in Australia is primarily as between left (Australian Labor Party (ALP)) and right (the Coalition). Those aligned to the right-of-centre tend to view the ABC as biased against them and their constituents (see Chapter 4 below), while the ‘other side of politics’ (to use Australian media terminology) to the left-of-centre, view News Corp press outlets as stacked against them ideologically. The ALP, for example, have accused News Corp press outlets, dominant in their sector, of anti-ALP bias in their coverage of politics, notably in the run-up to the 2013 general election. Without making conclusions as to the respective merits of these assertions, neither allegation of bias can be separated from the political context in which it is made. Bias is, and always has been, to a large extent in the eye of the beholder.

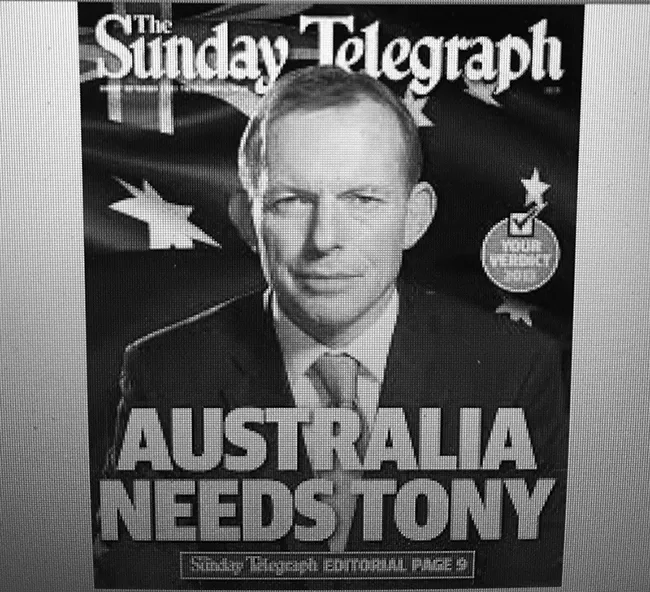

Although there is little evidence that such pro-Coalition, anti-ALP bias as was to be found in the Daily Telegraph and The Australian in the run-up to the 2013 election secured Tony Abbott’s narrow election victory (see Jonathan Green’s analysis of the coverage in The Drum8) front pages such as ‘Australia Needs Tony’ do hint at the cheerleading and ideological biases to be found in at least some of News Corp’s political coverage (Figure 1.1). Freedman observes of the UK “evidence that audiences are prepared to question media content and to adopt frames that run directly to counter to those pursued by mainstream media organisations” (2014: 116). In Australia, seats where the ALP did unexpectedly well in the 2013 election were often those with high penetration by the aggressively anti-ALP Daily Telegraph.

This is the background against which leading political actors, including both Labor and Coalition prime ministers, have argued that Australian media coverage of politics undermines effective democratic governance. In a special edition of ABC’s Q&A in 2013 (Figure 1.2), then-prime minister Julia Gillard made an interesting comment about what she perceived to be the weaknesses of the Australian political media, and their impact on the democratic process. Chairman Tony Jones had suggested that “polls suggest an awful lot of [people] are completely fed up with politics, bored with it, are turning away, turning off”. Gillard replied:

That does concern me … In terms of what happens, the mechanics of politics, I think it’s harder, with the quickness of the media cycle, the immediacy of it, to sustain some of the deeper debates that people want to see us have, and I think that does frustrate people. I’d like to find some better ways of doing that, I think our whole nation would, rather than some of the quick turnarounds, the conflict-driven media cycle. That’s a challenge for all of us as we adapt to this new information environment.

(ABC, Q&A, 6 May 2013)

In 2015, while still Minister for Communication in the Abbott government, Malcolm Turnbull called for a “less aggressive and more forensic” style of political interviewing, especially from the ABC, on the grounds that this would improve the quality of the information extracted in such exchanges.9 Echoing criticisms made also of political journalism in the UK and USA, and captured in James Fallow’s notion of hyperadversarialism (1996), Turnbull was blaming journalists for failing to engage politicians in ways which maximize the communication of useful information to their electorates. Many Australian commentators, particularly on the right of the political spectrum, have been especially critical of the ABC’s performance in this and other aspects of its public service remit.

Journalists, on the other hand, across the spectrum of Australia’s media organizations, regularly nominate the suppliers of political communication and the growth of political spin, high volumes of press releases and limited access to government and official sources as impacting adversely on their capacity for rigorous reportage and analysis of politics, as opposed to what Nick Davies has called churnalism (2008). From this perspective, the politicians and their efforts to manipulate media are a greater hindrance to the effectiveness of the political public sphere than the flaws of journalists, hyperadversarial or otherwise (McKnight, 2015).

As in comparable democracies such as the UK, Australia has seen regular media debate and commentary not just on key policy matters – the normatively preferred ‘substance’ of political communication and the political public sphere – but on the presentation of these by politicians (the ‘style’), the coverage of that presentational ‘horse race’ by media organizations (the ‘process’) and the impact of both on levels of democratic engagement by the Australian public. So dysfunctional is this political culture seen to have become that former prime minister Malcolm Fraser asserts that in Australia “the relationship between politicians and the media degrades public life and diminishes our future” (quoted in Tanner, 2011).

There is a temptation to dismiss such views as the predictable complaints of political elites confronted with unwelcome media scrutiny (the acceptance of media scrutiny by political elites has been a long and difficult journey, from the days when Winston Churchill had to be dragged unwillingly into the BBC TV studio to record a speech to camera, to the contemporary requirement for members of parliament (MPs) and government ministers to be available on public participation media formats such as the ABC’s Q&A (see Chapter 7). Inside and out of the spheres of politics, the media and the academy, however, in many of the mature liberal democracies, there is a justified, and non-partisan concern for the quality of governance as those societies face increasingly complex domestic and foreign policy challenges such as anthropogenic climate change, Islamist terrorism, mass migration and the risk of viral pandemics. Two decades after Blumler and Gurevitch’s influential work – a period shaped by the rise of 24-hour news culture and the internet, with the latter’s accompanying exponential growth in the quantity, velocity and reach of political information in circulation at any given time – the perception and rhetoric of crisis has not abated. In 2013 an article in Crikey magazine noted that 12 per cent of Australians had not voted in the general election of 2010 – not a high rate of disengagement by global standards, but more concerning for observers when voting is a legal requirement of citizenship. The article quoted a Labor MP who believed that “changes in the media are one of the factors making this group more disconnected from politics”.10 The success of independent politicians in Australia seen in the 2016 election – the election to Senate of One Nation leader Pauline Hanson, in particular– was read by many as evidence of public dissatisfaction with political elites. The election of Donald Trump as President of the United States in November 2016 was interpreted by many as evidence of mounting dissatisfaction globally.

The Dimensions of the Crisis

Jurgen Habermas asserts that the contemporary political sphere (or that which existed when he wrote these words in 2006) “is dominated by the kind of mediated communication that lacks the defining features of deliberation … The dynamics of mass communication are driven by the power of the media to select, and shape the presentation of messages, and by the strategic use of political and social power to influence the agendas as well as the triggering and framing of public issues” (2006: 416).

Two elements of the crisis are identified in this passage: first, the use (or abuse) of political power to influence ...