Constellation

The odd people who stood out in my early experience were the madwoman at the shrine (schizophrenia), the drinking man (alcohol dependency), and the violent man (personhood disorder).

After finishing my basic training as an intern at the university hospital, the first place I was sent was a specialized hospital for alcoholism. The clinical work with addicts was quite hard, and my energy was drained every day. Yet, I was absorbed in this field, thinking that drug and alcohol dependency might become my specialty. After a while, I had the opportunity to study at the C. G. Jung Institute in Zürich, Switzerland. After returning home from Switzerland, opportunities to lecture and write about personhood disorders began rolling in, which then absorbed me for some time.

As Agatha Christie (1944) said through one of her characters, “The story begins long before that – years before sometimes … And then, when the time comes … all of [it] converg[es] towards zero” (pp. 12–13). My journey as a psychiatrist “begins long before that,” at least as early as when I received strong impressions from the odd people in my town, such as the drinking man and the violent man. I might have unconsciously formed what “begins long before that” as a question to be asked of life. As it was, my clinical work and research on alcohol dependence and personhood disorders seemed to converge “towards zero.” It was downright strange. I cannot take it as just a coincidence, nor do I feel myself simply to be making it up. In retrospect, each instance seems to have been inevitable, though it never felt that way during my journey.

The drinking man and the violent man did have some sort of influence on my life. What I mean by influence here is something that shapes one’s destiny, something that moves one subtly yet powerfully in the psychic depths. In Jungian psychology, such a condition that is brought on with this kind of power is called a “constellation,” using an analogy from the stars at night.

The cause of existence

As for a mental attitude conducive to the discovery of such constellations, I would suggest one of leaning into the cause of existence.

It was when I wrote a paper entitled “Pilgrimage and the Cause of Existence” (Akita, 2000) 10 years ago that I used this term for the first time. Drawing on this paper, let me explain what the cause of existence is about.

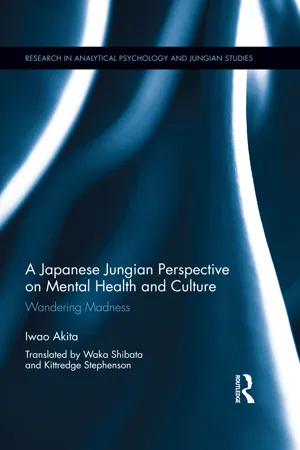

Around the time I was writing this paper, etiology was an important research question for me. Etiology is the cause of a disease, and in psychiatric medicine, the cause is described using terms such as endogenous cause, exogenous cause, or psychogenic cause. Here is how modern Western psychiatry categorizes the cause or formation of mental disorders. First, the cause is determined to be either a physiological or a psychogenic cause. Second, a physiological cause is determined to be either an endogenous cause or an exogenous cause (Figure 1.1). The endogenous type of physiological cause means a cause that is undefined as of yet, but whose biological base is expected to be understood in the future; schizophrenia and bipolar disorder are categorized as endogenous mental disorders. The exogenous type of physiological cause is often referred to simply as the exogenous cause, because the mental disorders with this cause can be explained in terms of physiological pathology: infection, intoxication, degeneration, and external injury are in this category. The sub-categories of exogenous causes in psychiatric medicine are organic psychoses, symptomatic psychoses, and mental disorders related to substances such as drugs and alcohol. The term psychogenic cause is used when a mental conflict is the cause of the mental disorder, such as a neurosis.

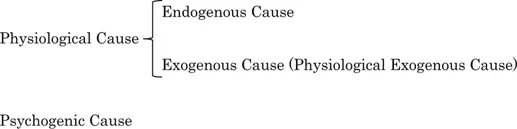

This taxonomy has as its central axis the distinction between the physiological cause and the psychological cause. There is another taxonomy that places the endogenous cause versus the exogenous cause at the center (Figure 1.2). Both the physiological–psychological cause axis and the endogenous–exogenous cause axis follow the two-category system: body–mind and endogenous–exogenous. The two-category system can provide a makeshift scientific explanation, but this dichotomy cannot answer the “why” question, as Kawai pointed out as early as 1967. Kawai said:

A man1 lost his fiancée in a traffic accident right before the wedding. He asks, “Why?” “Why did my fiancée die?” A doctor would answer, “It is due to the head injury, and ….” This answer is not incorrect. Yet, it will not satisfy him. How come this correct answer does not satisfy him? It is because the answer was given by converting the question of “why” to the question of “how” … In other words, natural science has accomplished today’s development by shifting from “why” to “how.”

(1967, pp. 2–3, our translation)

Unfortunately, the mental stance intent upon answering “why” questions is absent from the etiology of modern psychiatry. Once psychiatric medicine was incorporated into natural science, which had been developing by shifting from “why” to “how,” this was inevitable. It is a big issue for psychiatric medicine. What is worse, the issue is so large that even locating the problem is difficult. As the proverb says, “You can’t see the forest for the trees.” This forest is massive.

Psychiatric medicine, which should hold “why” questions at its center, must not be positioned merely as a branch of natural science. As long as it is positioned as psychiatric medicine, however, it can only function as a branch of medicine, which in turn serves as a branch of natural science. Getting out of this dilemma begins with recognizing this fact. Then, psychiatric medicine needs to shed its skin and regenerate towards psycheology.

Clients come on a daily basis. Psychiatric medicine is needed, i.e., psychiatric medicine needs to remain a branch of medicine. However, when psychiatric medicine substantially individuates itself as psycheology – that is, when psychiatric medicine maintains an attitude that concerns itself with “why” questions – it can soar into psycheology, which can transcend the logic of natural science. Such a spirit also needs to extend into other branches of medicine, because “why” questions overflow into all medical branches. Psychiatric medicine as psycheology needs to develop itself enough to exist in and support all of the other branches, including internal and emergency medicine. When Western medicine attains this perspective, the forest called psychiatric medicine, which includes even the woods of psychiatric medicine as psycheology, can become luxuriant and provide people with true rest.

Although the clinical practice of psychiatry is full of these “why” questions, the mental attitude to support answering them cannot be found in its etiology. The psychogenic cause is ostensibly responsible for addressing “why” questions, but it tends to be handled in the context of “how,” so “why” is once again excluded. Should the etiology of the psychogenic cause just grow and expand to the point of addressing “why” questions, then? That is not enough – because mental disorders due to endogenous and exogenous causes also carry “why” questions.

It is these “why” questions that house the attitude of searching for one’s cause of existence. The conceptual utility of endogenous, exogenous, and psychogenic causes does not need to be questioned. Clinicians, however, must be aware of the cause of existence in order to avoid ignoring the “why” questions that lurk and swirl in the abyss, and thus to be of help to those searching for their individuality. When the thirst for the cause of existence remains unquenched, some people step into fortune-telling, or even shady cults.

What is the cause of existence?

When therapists attempt to attune to their clients’ cause of existence, it provides a space in which clients can open into their individuality. It is this attitude that is necessary for psychiatric medicine itself to open up.

I have been using the phrase cause of existence without any definition so far in the hopes that you might get a sense for it, as this term can only be understood intuitively. Even so, I will add the following tentative explanation.

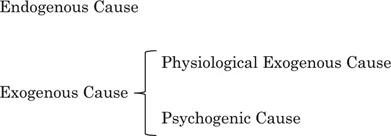

The intension2 of “existence” in the term cause of existence is “being.” No doubt about it. Descartes said, “I think, therefore I am” (1637/1952, p. 51). The “I” who thinks, or the ego, becomes the foundation of cognitive certainty. This has been the foundation for the conventional etiology of Western psychiatric medicine. In contrast, if we posit the cause of existence as underpinning a physiological, psychogenic, endogenous, or exogenous cause, the foundation for cognitive certainty becomes, “I am, therefore I am” (Figure 1.3). Furthermore, concepts such as fate, soul, Self, karma, reincarnation, cosmos, the law of causation, God, the devil, the collective unconscious, as well as the problems and tasks of humanity, can all be seen as extensions of this being.

Ten years ago, I wrote:

By the way, if you ask me whether I can conduct psychotherapy with the attitude of attuning myself to the cause of existence in my clinical practice, I am not 100% sure. Of course I am trying, but when I reflect on my clinical work in psychiatry, sometimes I see clients while distracted by my own thoughts, such as “Oh, I’m hungry,” or “I want to go home and watch the evening game with a glass of beer.” If clients saw into my mind, they might get angry.

(2000, p. 124, our translation)

I may have grown a bit since then, because such distractions rarely occur in therapy nowadays. Even if such worldly thoughts show up, I just let them flow around the rim of consciousness as worldly thoughts, rather than getting caught up in them, and I direct my mind straight into the essence that needs to be approached. The worldly thoughts may not have decreased so much as they have become less sticky.

I continued as follows:

However, when a therapist, who struggles with these worldly, evil, and delusional thoughts, still tries to be attuned in a prayerful fashion, sometimes the cause of existence can be seen intuitively in a moment of purity. Guggenbühl-Craig, one of my analysts, told me that there was also a time when he struggled with questions of why he had to live. When he looked at the mountain from the window, he suddenly realized, “Now I see – that’s it.”3 I wonder if this is similar to when one glimpses the cause of existence intuitively. Then, the internal process begins again, tracing the path of this new “opening.”

I wrote, “struggles with these worldly … thoughts,” but speaking candidly from my own experience, these worldly thoughts seem to be rather necessary sometimes to intuit the cause of existence, which enable one to survive this life. When we try to reach out towards this “opening” for living, these sloppy thoughts might be essential ingredients.

(p. 124)

This is also a bit different from how I perceive things now. You may think that I should limit myself to discussing only the most developed or latest ideas that have come to me with more experience. Assuming that the ages and experiences of readers will vary, however, I decided to include my clinical approach to this 10 years ago in the hopes that it may be of some use.

As I mentioned, I suffer less from worldly, evil, or delusional thoughts than before. At the same time, the sense of bringing a prayerful attitude into psychotherapy has decreased as well. No. Rather, I would like to believe that this attitude has been acquired to the point that I don’t have to be so aware of this sense of praying anymore. I use the term “believe” because, despite this process taking place within myself, it is too delicate for me to be sure.

I used to be keenly aware of evil influences, so the sense of praying also stood out to me. But the boundary between evil, worldly, obsessive, and delusional thoughts has become more vague with time. This applies to prayer as well. The purity with which prayer is practiced and the ends it is asked to serve differ depending on one’s perspective – it is the prayerful intention that is holy.

My present clinical approach is to direct my mind towards the cause of existence, while letting everything – including evil, worldly, and prayerful thoughts – float around the extension of the existence. I feel like I am slowly sinking down towards the cause of existence in order to catch a glimpse of something ethereal. I protect myself with only a thin layer of psychological cosmetics (kokoro-gesō),4 attempting to descend with a mind as free from worldly thoughts as possible. The degree of freedom is much higher than before, as worldly thoughts have become less sticky. My ability to reach further to the right, left, forward, and backward seems to have increased.