![]()

1 Emotion and the Translation Process

While there are many theories of translation, very little has been written about the everyday psychology of translating.

—Alice Kaplan

Language and emotions are inextricably linked, as emotional factors are embedded in the dynamics of multilingual discourses and, in turn, languages shape individuals’ emotional landscape. The picture that emerges from research on emotions and languages is a complex and dynamic one. It suggests that the perception, processing, and communication of emotions in various languages is partly linked to past and present experiences, and partly linked to a range of psychological and sociobiographical factors. As a form of communication involving language, translation will necessarily involve emotion. Translation and emotion therefore seem to be an obvious combination for research study.

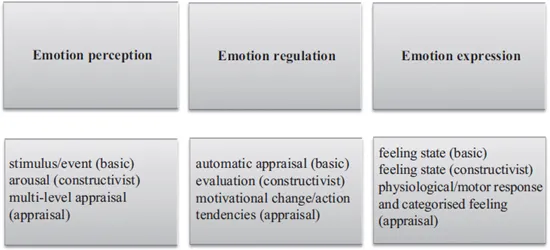

The purpose of this monograph is to review recent literature in three specific areas of emotion in the fields of Psychology and Translation Studies and use it to inform an empirical case study involving professional translators. ‘Translation’ is a broad concept and area of study, if we take translation to mean any kind of transfer and transformation (Brownlie 2016, 1). ‘Emotion’ can also be interpreted broadly as many different phenomena fall under this heading. Emotions can be broadly defined as multifaceted, embodied phenomena that involve loosely coupled changes in subjective experience, behaviour, and peripheral physiology (Mauss et al. 2006). The three subsequent chapters of this monograph each focus on a key aspect of emotion processing: emotion perception, emotion regulation, and emotion expression.

In the present chapter, I first define the psychological construct of emotion and explain how it will be operationalised in this monograph. I then consider how translation process research has developed to take account of emotional phenomena, and review pioneering recent studies that have explored aspects of translators’ emotions. Following this, I introduce the case study and explain how translation has been tackled throughout this work. By exploring the role of emotions in translation, my interest is directed mainly towards understanding in what ways affect influences translators in their professional lives, regardless of their specialisation or field, particularly in light of recent advances in emotion research.

Emotions in Psychology

Definitions and Theoretical Frameworks

‘Emotion’ has been described as a keyword in crisis in modern Psychology (Dixon 2012). This could be due to the fact that there seems to be little scientific consensus regarding what an emotion actually consists of or which states and processes are parts of it. Sometimes called ‘emotion science’ or ‘affective science’ because it has drawn for centuries from areas as diverse as neuroscience and genetics, the study of emotions has produced a wide range of definitions for this object of study, stemming from many different disciplines (Frijda and Scherer 2009, 142). Nevertheless, there is some agreement among the scientific community as regards the following features: Emotions arise when an individual considers the situation meaningful to his or her goals, emotion-evoking events require the organism to react, thus affecting behaviour, and, finally, emotions can interrupt and claim priority over what we are doing, although these interruptions are not always granted precedence (Suri, Sheppes, and Gross 2013).

In recent years, the sharp distinction that had traditionally been made between rational thought and so-called subjective feelings has been heavily challenged, as it has become apparent that cognition and emotion are not isolated entities (Robinson, Watkins, and Harmon-Jones 2013, 4). Although the exact nature of the relationship between affect and cognition is not universally agreed on, there is an increasing tendency to consider affect as integrated with cognition, and cognitive functions are viewed as necessary components for understanding emotion processing. The following quotation from Phelps (2006, 44/46) summarises this view:

Although certain stimuli may be prone to evoke an emotional reaction, how those stimuli are processed and interpreted can have a profound impact on both internal states and expressed behaviours and actions. Through conscious strategies and practice, individuals can change their interpretation of specific stimuli, and this can alter emotional reactions. Changing emotional responses through reasoning and strategies emphasizes the impact of cognition on emotion […] [t]he mechanisms of emotion and cognition appear to be intertwined at all stages of stimulus processing and their distinction can be difficult.

Emotion and cognition therefore interact in order to guide behaviour. Despite concurring that (1) emotion is a multicomponent process comprising different mechanisms not linearly organised, and (2) there is value in considering emotion and cognition together, emotion researchers still lack consensus on a unified theoretical framework to study emotions. Pavlenko (2012, 408/409), who researched affective processing in bilinguals and multilinguals, distinguished three major currents emerging from different schools of thought:

Basic emotion theories see primary affective processing as discrete innate responses that precede cognitive judgments and are independent of language […] [a]ppraisal theories see affective processing as subjective evaluation of stimuli with respect to their relevance for the individual’s goals, values, and needs that triggers changes in endocrine, autonomic, and somatic nervous systems […] [c]onstructionist theories deny the existence of “non-affective” thought (Duncan and Barrett 2007) and see affect as cognition, a transformation of the organism’s neurophysiological and somatovisceral state (core affect) into experiences understood in terms of language-specific emotion words.

[my emphasis]

Not all psychological emotion theories fit neatly into the three theoretical traditions outlined above, however, and there is much variation in emotion research both in terms of terminology, underlying mechanisms, and methods employed. Nevertheless, some consensus does exist regarding the following components of emotion: elicitation processes, physiological symptoms, motor expression, motivational changes, and subjective feeling (Scherer 2009, 148). Despite the use of somewhat static models, scholars also tend to converge on the idea that emotion processes are dynamic and recursive.

Given the focus on translation in this work, my goal is not to provide a complete account of different emotion theories here. Specific literature reviews are provided at the start of each of the subsequent chapters which are tailored to the stage of emotion processing addressed in that particular chapter (e.g. emotion perception, regulation, and expression). Nevertheless, these stages of emotion processing were chosen because they feature in one way or another in the various models emerging from different emotion theories, albeit using different nomenclature. As Gross (2008, 703) sums up, there is consensus that (1) emotions arise in a situation that compels attention, (2) emotions are then assessed, and (3) this gives rise to a complex response. To illustrate very simply how the constructs1 employed in this study broadly map onto existing models, please refer to Figure 1.1.

In this book, my aim is to incorporate insights from different emotion theories when discussing the three stages of emotion mentioned above and assessing their relevance for translation. As both emotion and translation are interdisciplinary in nature, it seemed appropriate to integrate relevant insights from emotion research in a broad sense to serve the needs of the present study. Scherer (2009, 150) highlights that “most [emotion] theories do not fundamentally contradict each other; rather, they differ in the degree of emphasis they place on elicitation, response organization, action preparation, or conceptualization”. As such, I will point to relevant concepts and theories from these adjacent areas in order to shed light on the phenomena under consideration. The terms affect, emotions, and feelings will be used according to the emotion theory or framework being discussed, and like Pavlenko (2012), I will not assign undue significance to the fact that English provides us with different terms in this area.

Figure 1.1 Simplified mapping of study concepts onto three existing traditions of emotion theories

Another aspect of emotion that has been hotly debated is the breadth of its domain and whether to distinguish between occurrent states (emotions that have a limited duration) and dispositions (emotional attitudes or traits that may persist over a lifetime). This aspect is relevant here, as the case study explores translators’ traits, but the literature reviewed also refers to research where the focus is on occurrent states, because of its relevance for translator behaviour. This approach is justified as occurrent emotions and persistent dispositions share the same structure and “can both be characterized by an object, its appraisal, and a particular propensity to act in relation to the object—a latent, dispositional propensity in the case of sentiments, and an acute, occurrent propensity in the case of emotions proper” (Frijda 2008, 73). In a recent article, Oatley and Johnson-Laird (2014, 137) showed that different emotional phenomena have different durations, with some lasting only a few seconds and others, such as emotion-based traits of personality, lasting a lifetime. While a so-called full-blown emotion is said to represent an integration of feeling, action, and appraisal at a particular time and location, personality represents integration over time and space of these components (Ortony, Norman, and Revelle 2005). According to Revelle and Scherer (2009, 304),

[t]rait differences in emotionality2 increase the odds of experiencing trait-congruent emotions. In other words, individuals high on trait anxiety run an increased risk of experiencing anxiety bouts, individuals high on trait anger get irritated more often, and so forth.

Therefore, in order to shed light on the different ways that emotions can guide translator behaviour, the distinction between occurrent states and persisting traits can be viewed in terms of a continuum rather than discrete categories. The following chapters combine research from the study of long-term affect with short-term fluctuations in emotion in order to obtain a more integrated view of translators’ emotional processes. As Frijda (2008, 84) indicates, comparing findings and explanations at different levels is a profitable enterprise.

Personality and Emotion

The literature suggests that early and repetitive emotional experiences can result in structural changes that become consolidated in personality.3 These changes turn into stable affective traits that give rise to enduring expectations colouring the individual’s affective world and behaviour in predictable ways (Magai 2008). Interestingly, Revelle and Scherer (2009, 304–305) highlight that these habitual affective traits (i.e. dispositions to experiencing some types of emotions more frequently than other people) are reflected in basic neural processes; functional brain mapping has shown that various affective traits are associated with activation in different brain regions when individuals are shown positively and/or negatively valenced slides (Revelle and Scherer 2009).

As previously mentioned, there are competing theories and frameworks when it comes to the study of emotions, and the present volume attempts to review and integrate research from these various areas to shed light on particular aspects, or stages, of translators’ emotion processing. The case study itself, however, focuses on trait emotional intelligence and is thus rooted in personality psychology and trait theory more specifically. In the case study, my intention is to explore professional translators’ individual differences in emotion processing at the level of personality, and exploring their trait-level characteristics seemed to be a more reliable way of doing this than did analysing individual instances of behaviour. Alternative approaches for studying personality were nevertheless considered. For instance,

[the] processing approach construes personality as an organized system of mediating units […] and cognitive-affective dynamics, conscious and unconscious, that interact with the situation the individual experiences […] the basic concern has been to discover general principles about how the mind operates and influences social behaviour as the person interacts with social situations, conceptualized within a broadly social-cognitive theoretical framework.

(Mischel and Shoda 2008, 209)

Social-cognitive approaches offer a valuable alternative account of personality to trait approaches. Barenbaum and Winter (2008, 15) claim that while trait psychologists had long recognised the importance of the self, the cognitive revolution brought a proliferation of “self-”related variables, including the theory of self-concept which is rooted in social-cognitive approaches. The self-concept explains how people perceive and regulate themselves, as well as providing a lens for interpreting other people’s behaviours, something which is said to involve cognitive appraisals (Fiske and Taylor 2013). Whatever their theoretical origins, however, it is claimed that individual difference variables such as self-efficacy appear closely related to traits on an empirical level. Indeed, McCrae and Costa (2008, 160) state that most psychological questionnaires measure some form of personality trait. In addition, social-cognitive approaches have often been criticised for neglecting to take account of the stable dispositional differences between individuals (Mischel and Shoda 2008, 209). The use of trait theory as a framework for the present case study is rooted in the belief that there are certain stable personality traits and behavioural dispositions that are helpful for successful translation and others that are less so. Trait theory, in my view, also enables the characterisation and understanding of translators and the differences between them. According to McCrae and Costa (2012, 15), trait models of personality are compatible with a wide variety of theoretical approaches and have formed the basis for most research on personality.

It is important to acknowledge that trait approaches have also been criticised, notably for not fully addressing the psychological processes that underlie behaviours and, thus, for not making behavioural change easy to achieve; indeed, Mischel and Shoda (2008, 209) note that it is one thing to generalise about a population’s traits and their similarities and differences but quite another to explain what l...