![]()

1 | Writing American Consumption History |

This introductory chapter provides some conceptual and methodological grounding for researching and writing American consumption history. It examines a few basic concepts of consumption and consumer culture, some issues and literature in consumption historiography, types of data sources for consumption history, approaches to the analysis of material artifacts, the topic of historical periodization, and the structuring and scope of this book. The next chapter discusses the history of the field of consumer research, as well as consumer culture theory perspectives on meaning, gender, and resistance that are the threads that inform and guide this history.

Consumption and Consumer Cultures

Consumption history is about what consumers have done in the past, but also an account of what they and critical observers (e.g., theologians, social commentators, politicians, and activists) have thought, felt, and said about consumer behavior. Consumers in this book are to be considered people (i.e., end-users of goods and services), not companies or governments, and their consumption behavior entails a broad range of acquisition, use, and recycling or disposal activities. In modern economies, acquisition largely results from shopping and buyer behavior in a commercial marketplace. This requires personal income. However, the United Nations Human Development Programme reminds us that much consumption is collective and non-material (HDR 1998). People also consume a wide variety of goods and services from sources outside the market including nature (e.g., hunting, fishing, gathering), unpaid work (e.g., domestic activities, self-production), and public provisioning (e.g., food stamps, subsidized water, sanitation services). In the distant past, nature and unpaid work undoubtedly accounted for much consumption.

The meanings of the terms “consumption” and “consumer” have changed over time. Historian Lawrence Glickman (2009) showed how in eighteenth-century America to consume meant essentially “to use” or “to use up” something. Purchasing was seen as a separate activity. In the nineteenth century, consumption became understood, like it is today, to include the buying of both goods and services and to be the driving force of economic activity. The word “consumer” began to be used in its modern sense in the 1820s. In the twentieth century, the consumer was identified as a separate class of social actor that in the aggregate constituted the target market for sellers, but also needed protection from the vagaries of the market.

Historians and consumer culture theorists have long debated the meaning of the interrelated terms “consumer society,” “consumerism,” and “culture of consumption.” Two perspectives will suffice for our purposes. First, Kathleen Rassuli and Stanley Hollander (1986, 5) argued that a culture of consumption required four conditions:

1 People (or some very substantial segment of the population) consume at a level substantially above that of crude, survival-level subsistence.

2 People obtain goods and services for consumption through exchange rather than self-production.

3 Consumption is seen as an acceptable and appropriate activity.

4 People, in fact, tend to judge others and perhaps themselves in terms of their consuming lifestyles.

As Russell Belk (1996) observed, the choice of the word “crude” to characterize subsistence hunting and gathering was potentially biased, but the last two requirements of this definition do highlight the importance of belief and value systems in addition to basic economic conditions.

Second, in his fine and learned book, Consumer Culture and Modernity, Don Slater (1997, 24–32) identified a number of features of a modern consumer society. These signposts included the following (Slater’s statements in italics):

1 Consumer culture is a culture of consumption. This is Slater’s way of saying that the values of consumption prevail in consumer cultures and inexorably spread into numerous domains of social action.

2 Consumer culture is the culture of a market society. In other words, we generally consume goods and services made and distributed by others primarily within a capitalist system.

3 Consumer culture is, in principle, universal and impersonal. This observation reaffirms the idea of “mass consumption” where buyers are usually unknown to sellers. Everyone, in theory, has the right to consume and “all social relations, activities and objects can in principle be exchanged as commodities” (Slater 1997, 27).

4 Consumer culture identifies freedom with private choice and private life. This statement embodies the arguably mythical, but heavily promoted notions of “consumer sovereignty,” a “democracy of goods,” and the consumer as “voter,” “judge,” and “jury” (Schwarzkopf 2011).

5 Consumer needs are in principle unlimited and insatiable. Ever growing demand, once considered a social or moral pathology in some cultures, and a status marker reserved for elites in others, becomes normalized and a prerequisite for progress in consumer cultures (see, e.g., Campbell 1987; Mukherji 1983).

6 Consumer culture is the privileged medium for negotiating identity and status within a post-traditional society. Here, fixed social orders – often reinforced by sumptuary laws regulating food, clothing, and luxuries – are swept away and identity becomes a function of consumption.

7 Consumer culture represents the increasing importance of culture in the modern exercise of power. Symbols, especially brands, conveyed by advertising, packaging become preeminent in consumer culture.

Historically, America did not become a consumer culture in Slater’s full sense until the twentieth century, but as will be shown several of these features became apparent by the mid-eighteenth century, at least within some colonial circles, and these and other criteria became increasingly widespread over time. This is why it may be more appropriate to use the plural “consumer cultures” when referring to the past, just as it would be when alluding to different societies in the present.

Consumption Historiography

History is a branch of knowledge dealing with past events, as well as with the evolution of ideas within their larger societal contexts. Sometimes, academics in marketing and consumer research regard history as a methodology. This view is mistaken. History is a subject area in the same sense as advertising, retailing, and services marketing are topics of study. Although historical data can be used to investigate theories developed by the social sciences, history as a discipline is very much concerned with addressing historical questions. So, when discussing methods for researching the past, the appropriate term is historiography, which refers to the principles, theories, and methodologies of historical writing. Note that the term “history” also refers to a chronicle or narrative of the past and that the term “historiography” too has a second meaning, as a body of literature. This section reports on some relevant literature, mainly that created by academics in marketing and consumer research, and is then followed by a further look into some methodological issues.

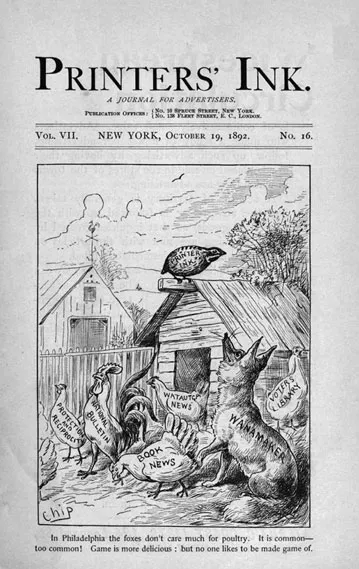

In the fields of economic, business, and marketing history, the majority of research concentrates on past practices and events, but a sizeable minority examines the evolution of economic, business, and marketing thought (Witkowski and Jones 2006). Similarly, historical studies of consumption patterns focus on past behavior and happenings, whereas investigations of market ideologies over time relate to the field of intellectual history or how thinking about consumers and consumption has evolved. An example of the latter was Merle Curti’s (1967) “The Changing Concept of ‘Human Nature’ in the Literature of American Advertising.” Based on an analysis of articles published from 1888 to 1954 in Printers’ Ink, a pioneering advertising trade journal (see Figure 1.1), Curti documented a shift from envisioning the consumer as a rational, self-interested actor to one moved more by emotions and non-rational drives. Ronald Fullerton’s (2007) “Psychoanalyzing Kleptomania” offered another exemplar of intellectual history in consumer research. Descriptions of consumer theft and shoplifting behaviors have been stable for 200 years, but explanations have ranged from “lesions of will” in the nineteenth century to Freudian notions of sexual significance and Adlerian inferiority complexes in the twentieth century to contemporary emphases on chemical imbalances treatable by pharmaceuticals.

Figure 1.1 Printers’ Ink, October 19, 1892. Founded in 1888 by early adman George P. Rowell (1838–1908), this cover referred to a dispute with retailer John Wanamaker (the fox) who had been appointed Postmaster General in 1889 and who charged Printers’ Ink (the game bird) a higher postage rate than he did for his own trade publication, Book News (the center chicken).

A review of the methods literature in consumption and consumer culture historiography should begin with Ronald Savitt’s (1980) “Historical Research in Marketing,” published in the Journal of Marketing. Savitt argued that historical research should be conducted according to the philosophies of positivism and empiricism: “Historical research must retain the objectivity of the scientific method, following its structure as closely as possible” (Savitt 1980, 54). His outline of historical research included seven activities: (1) problem definition, (2) literature review, (3) formulation of hypotheses, (4) research design, (5) data collection, (6) hypothesis verification, and (7) theory development. Contributing to theory is not the only and perhaps not even the most important justification for historical work in marketing and consumption, but researchers trained in the social sciences have taken this purpose seriously. Savitt’s article helped stimulate renewed interest in history among marketing academics and consumer researchers.

The 1987 meeting of the Association for Consumer Research (ACR) featured five presentations on consumer historiography. Of this group, Ronald Fullerton’s (1987) “Historicism: What It Is, and What It Means for Consumer Research,” has had a great influence on my own thinking. The German historical school, in a challenge to logical positivism, was skeptical of law-like generalizations and cumulative social knowledge. Its proponents argued that societies are constantly in flux and that theories having credence in one time period may no longer be so relevant at a later date (Fullerton 1987). Events were considered “historical individuals” and so researchers should focus on concrete social phenomena. Stated differently, the focus of historical research should be on addressing particular historical issues and questions, not on building universal theories (Smith and Lux 1993). Thus, some professional historians have identified more with the humanities, whereas others have leaned toward the social sciences. In practice, a given study might serve either historical or theoretical ends or both simultaneously in various proportions. Indeed, historical inquiry sometimes is based upon the perspective of a particular theory, such as neo-Marxism or feminism.

Also among the 1987 ACR papers were “Historiography, Scientific Method, and Exceptional Historical Events” by Fuat Firat, “An Historical Perspective Framework to Study Consumer Behavior and Retailing Systems” by Erdogan Kumcu, “Comparative History as a Research Tool in Consumer Behavior” by Kathleen Rassuli and Stanley Hollander, and “Insights into Consumer Behavior from Historical Studies of Advertising” by Richard Pollay. Firat (1987) compared different traditions in historiography – specifically, the French Annales school of history, hermeneutic interpretation, and Marxist analysis – and explored their philosophical implications. Kumcu (1987) approached the study of consumer history as an alternative to logical positivism as a paradigm for understanding change in retailing systems. Rassuli and Hollander (1987) discussed data sources for comparative consumer history and proposed a model accompanied by examples for conducting this type of research. Pollay (1987) championed the potential of historical methods through reviews of Curti’s (1967) article and the then recently published books by Roland Marchand (1985) and William Leiss, Stephen Kline, and Sut Jhally (1986).

Two years later in “The Relevance of Historical Method for Marketing Research,” a chapter in the ACR-sponsored book, Interpretive Consumer Research, Marilyn Lavin and Thomas Archdeacon explored the relationship between interpretive (qualitative) and scientific (quantitative and deductive) approaches. Lavin and Archdeacon (1989) implicitly criticized Savitt’s (1980) model as too narrow and, for good measure, took a potshot at German historicism, which they depicted as “a philosophically dubious viewpoint” (60).

In “Historical Method in Consumer Research: Developing Causal Explanations of Change,” Ruth Anne Smith and David S. Lux (1993) deployed historical research in order to explain change in consumer behavior. Their conceptual model of historical methodology consisted of two stages: (1) Research Design, which includes question framing and research procedures, and (2) Historical Analysis, which entails investigation (discovery of facts), synthesis (construction of causal statements and writing an explanatory narrative), and interpretation or the “implications of the narrative for the research question” (605). The following year, I added my own two cents with “Data Sources for American Consumption History: An Introduction, Analysis, and Application,” a chapter in Explorations in the History of Marketing, the sixth supplement in the series Research in Marketing (Witkowski 1994). Among various topics, I discussed colonial probate records and household furnishings as potential data sources, and conducted a little experiment using material culture methodology, which I will revisit later in this chapter.

Three chapters in the Handbook of Qualitative Research Methods in Marketing, edited by Russell W. Belk and published in 2006, contributed to the historiography of consumption. Linda Scott, Jason Chambers, and Katherine Sredl (2006) in “The Monticello Correction: Consumption in History” explored issues related to who should be the subject of historical inquiry – elites and rich people or the everyday variety – and issues related to presentism, letting preconceptions from the researcher’s time influence views of the past. Richard Elliott and Andrea Davies (2006) in “Using Oral History in Consumer Research” explained this retrospective interview method and then presented some findings regarding the evolution of brand consciousness and consumer culture in the UK. In “Qualitative Historical Research in Marketing” (Witkowski and Jones 2006), my good colleague Brian Jones and I covered a range of practical topics including selecting a topic, source materials and their assembly, analysis and writing, and preparing manuscripts for marketing journals. Marketing and consumer research are social science driven fields and thus have different requirements than journals catering to academic historians. For example, historians generally have not been very transparent about research methods and, aside from discussions of sources, their writings do not include detailed accounts of methodology (Fullerton 2011).

In 2011, the Journal of Historical Research in Marketing featured a primer on oral history methodology “A Life Course Perspective of Family Meals Via the Life Grid Method” by Robert Harrison, Ann Veeck, and James Gentry. Later that year, the Journal put out an entire special issue on “historical methods and historical research in marketing.” Several articles are very relevant to researching and writing the history of consumer culture. Ron Fullerton’s (2011) autobiographical article on “Historical Methodology” drew upon his background as a professionally trained historian. He advocated strongly for consulting primary sources (evidence created during the period under consideration), understanding the past on its own terms, reading data critically, and giving high importance to interpretation and coherent story telling. In “Voices Passed,” Andrea Davies (2011) critically examined oral history, the reconstruction of the bygone events and feelings from interviews with surviving eyewitnesses. This method remains contested among historians who observe that individual recollections of events are unreliable and interact with public, group, and family memories. Rick Pollay (2011) in “Biographic and Bibliographic Recollections,” told how his collecting of advertising and promotional ephemera led first to original content analyses of evolving cultural values and ultimately to his becoming an expert witness in tobacco litigation.

In fusing his collecting passion with serious historical research, Rick has been a person after my own heart. Other collector/scholars who have contributed to consumption history include Janet L. Borgerson and Jonathan E. Schroeder. They have repurposed their collecting of Peter Pauper Press books from the 1950s and 1960s into a chapter on collecting, and have leveraged their collection of vinyl record albums and covers from the same era into several papers, Consumer Culture Theory conference presentations, and a book (Borgerson and Schroeder 2002, 2006, 2017). For more than a century, collectors and dealers have stimulated much art history research and decorative arts scholarship. Originally focused on objects and their makers, by the 1980s these studies of material culture increasingly were exploring consumer culture issues (Martin 1993).

On a final historiographical note, Brian Jones and I published an article, “Historical Research in Marketing: Literature, Knowledge, and Disciplinary Status,” in Information & Culture: A Journal of History (Witkowski and Jones 2016). In it we discussed how the literature in marketing history has grown, in part because of the dedication of key scholars who organized conferences, arranged for special issues, and launched journals. We also demonstrated how marketing history writing has developed some distinguishing features – explicit literature reviews, data borrowing, multiple types of primary sources, and methodological transparency – that reflect the social science background of many writers and, accordingly, meet the expectations of editors and reviewers for marketing journals. Since much consumer research has become closely identified with the marketing field, what applies to marketing history generally applies to the writing of consumption history, this book in particular.

Data Sources for Consumption History

Historians distinguish between primary and secondary data sources. Primary sources are forms of evidence produced during the historical period under investigation or, in the cases of autobiography and oral history, ...