This is a test

- 332 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

First published in 1994, this volume brings together essays from the celebrated scholar of African history, Nehemia Levtzion. The articles cover a wide range of themes including Islamization, Islam in politics, Islamic revolutions and the work of the historian in studying this field. This collection is a rich source of supplementary material to Professor Levtzion's major publications on Islam in West Africa.

This book will be of key interest to those studying Islamic and West African history.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Islam in West Africa by Nehemia Levtzion in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Teologia e religione & Religione. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

XIV

IBN-ḤAWQAL THE CHEQUE, AND AWDAGHOST

THE records of the Arab geographers provide the earliest documentary evidence for the history of the Western Sudan. Modern historians use these sources extensively, mainly through translations into European languages. Yet they have paid more attention to analysing the information available in these sources for the reconstruction of history, than to a critical study of the way in which such information reached the Arab geographers. Such a study is all the more important because too much is sometimes inferred from the few and thin references to the Western Sudan before the eleventh century.

The Arab geographers may be divided into three categories according to the regions where they could have acquired their information; that is to say in the eastern provinces of the Muslim world, in the Maghrib and Spain, or south of the Sahara in the Sudan itself. It may be presumed that the nearer the author came to the region he was describing the more detailed and reliable his information would tend to be. It is almost unnecessary to add that later geographers benefited both from earlier records and from the fact that the growth of the trans-Saharan trade over the centuries brought the Western Sudan nearer to the Muslim world. Indeed, in all periods traders were the principal informants providing geographers with information about remote countries.

Arab geography first developed in the east, in Baghdad and the Iranian provinces of the Muslim world, where the geographical knowledge of Iran, India, and Greece was transmitted to the Arabs. The expansion of the Muslim dominions and the development of trade inside the empire and across its borders widened the horizons of the world known to the Arabs.1 Al-Fazārī, who wrote towards the end of the eighth century, and represented the school influenced by Indian geography, was the first—as far as we know—to mention ‘Ghana, the land of gold’.2 Al-Khwārizmī, who died after 847 (232 a.h.), represented the Greek contribution to Muslim geography. He made an Arabic adaptation of Ptolemy’s Geography, adding to Ptolemy’s map geographical names unknown to the classics, inter alia the names of Zaghāwa, Kawkaw, and Ghana.3

These few names of towns and kingdoms in the Sudan reached the inquisitive geographers in Baghdad through Muslim traders who had been operating in the Maghrib, and had become involved in the trans-Saharan trade. Al-Yaʿqūbī, writing in 891 (278 a.h.), mentioned traders from Khurāsān, al-Baṣra, and al-Kūfa in Zuwaila, a centre for the slave trade with the Sudan.4 Al-Yaʿqūbī collected some of his information on the Sudan while he was working in the service of the Ṭāhirids in Khurāsān, before 872 (259 a.h.), and the rest after he moved to Egypt, when he also visited the Maghrib, including the Ibaḍite principality of Tāhert.5 Al-Yaʿqūbī’s information will be discussed later in this paper, but it should be noted at this stage that he was the first geographer to do more than give a mere list of names, and to provide us with concrete information about the kingdoms of the Sudan.

With al-Yaʿqūbī one enters a new phase in the ‘discovery’ of the Sudan. He was followed by Ibn al-Faqīh al-Hamadhānī, writing ca. 903 (290 a.h.), and al-Masʿūdī, who died in 956 (345 a.h.). These two borrowed much of their information on the Western Sudan from al-Yaʿqūbī, though each had something new to add. New pieces of information, however, brought no radical change in the degree of knowledge about the Sudan. Such a change occurred only in 1067/8 (460 a.h.), when Abū ‘Ubayd al-Bakrī wrote the first detailed description of the Western Sudan, which allows a more solid reconstruction of the history of that region.

While reading al-Bakrī’s description of the Western Sudan one is tempted to believe that he must have visited this region to get such an intimate knowledge of it. Yet it is certain that he produced this work in Cordova from reports and tales of traders and visitors to the Sudan. On the other hand, it is generally held by scholars that an earlier geographer, Ibn-Ḥawqal, crossed the Sahara and visited Awdaghost in 951/2 (340 a.h.), and so was the first Arab author who reached the frontiers of bilād al-Sūdān. It is the purpose of this paper to cast some doubts on Ibn-Ḥawqal’s visit to Awdaghost, and to suggest that we,have to wait four centuries more, until the middle of the fourteenth century, for a report by a traveller who undoubtedly himself crossed the Sahara. Ibn-Baṭṭūṭa’s travels, with itineraries and dates, are clearly recorded in his accounts, which are full also of his personal experiences in these remote countries. On the other hand, Ibn-Ḥawqal’s visit to Awdaghost may only be inferred from what he said about a cheque he saw in Awdaghost.

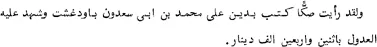

The famous cheque from Awdaghost is mentioned three times by Ibn-Ḥawqal.

(1) When introducing his chapter on the Maghrib, Ibn-Ḥawqal described the shift of the caravan trade from a route which linked Egypt and Ghana, over al-Wāḥāt (‘the oases’), to a new western trans-Saharan route from Sijilmāsa to the Sudan. He then went on to describe the great volume of the trade and the enormous profits of the traders of Sijilmāsa. This is demonstrated by the following anecdote:

I saw a bill [or a cheque] of a debt owed by Muḥammad ibn Abī Saʿdūn, written in Awdaghost and countersigned by competent witnesses, in the sum of 42,000 dinars.6

(2) In his description of Sijilmāsa, Ibn-Ḥawqal had many good things to say about this town and its people. The trade across the Sahara flourished, and the story of the cheque again served to demonstrate the prosperity of Sijilmāsa:

I saw a bill in Awdaghost certifying a debt owed to one of them [of the people of Sijilmāsa] by one of the traders of Awdaghost, who was himself of the people of Sijilmāsa, in the sum of 42,000 dinars. I have never seen or heard anything comparable to this story in the east. I told it in al-‘Irāq, in Fārs, and in Khurāsān, and everywhere it was regarded as a novelty.7

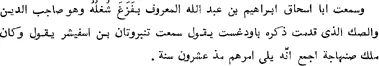

(3) Ibn-Ḥawqal met one of the participants in this exceptional monetary transaction, from whom he was able to obtain information on the political developments among the Ṣanhāja of the southern Sahara, in the neighbourhood of Awdaghost:

Abū-Isḥāq Ibrāhīm ibn ʿAbdallāh, known as Faragha Shughluhu, who is the creditor and the holder of the bill mentioned above in [connexion with] Awdaghost, told me about Tinbarūtān ibn Isfaishar, saying that he was the king of all the Ṣanhāja, and that he had been reigning over them already for twenty years.8

These three references allow us to reconstruct the whole transaction. Muḥammad ibn Abī Saʿdūn, originally from Sijilmāsa, settled to trade in Awdaghost. He owed a debt of 42,000 dinars to Abū-Isḥāq Ibrāhīm ibn ‘Abdallāh, a trader from Sijilmāsa. A bill certifying this debt was written in Awdaghost, and was countersigned by competent witnesses.

A debt of this amount, unheard of in the eastern provinces of the Muslim world, indicates a flourishing trade across the desert between two termini of the trans-Saharan trails, Sijilmāsa and Awdaghost. For a later period—the fourteenth century—we have a detailed account of the organization of the trans-Saharan trade, with partners in the trading centres north and south of the Sahara. Five brothers of the Maqqarī family settled in Tlemsen, Sijilmāsa, and Walata, from which places they could control the trans-Saharan trade in all its stages, by responding to the fluctuations of supply and demand at both ends of the route.9 In the fourteenth century it was a family partnership, whereas the tenth-century partnership was based on a business relationship, as suggested by the bill of debt. Yet the trading system was probably the same, with one partner resident in Sijilmāsa while the other moved south, across the Sahara, to settle in Awdaghost. (The latter was replaced by Walata as the southern terminus more than two centuries later.)

The bill of debt, as was to be expected according to the usual procedure, was held by the creditor, Abū-Isḥāq Ibrāhīm of Sijilmāsa. It was probably in Sijilmāsa that Ibn-Ḥawqal me...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Original Title Page

- Original Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Islamization

- Islam in Politics: The Role of the ‘Ulama’

- Background to the Islamic Revolutions

- Historical Studies

- Textual Studies

- Index