![]()

1

A fine genius for gardening

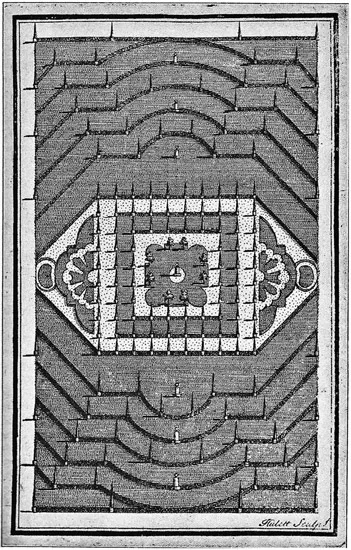

Figure 1.1 Kensington Palace, London: gravel-pit amphitheatre (north to top). Plan reproduced from Thomas Tickell, Kensington Gardens, 1722. Private collection.

As his is the first history of gardening Switzer begins it with a little trepidation and an apology for presuming to venture into a subject where readers might rather expect “valiant Atchievements, Heroick Examples and Lives of Great Soldiers, and the solemn Debates and Councils of Learned Statesmen and Senators …” (IR I 1). He goes on to argue that gardening, unlike high deeds, is the concern of many, if not all, and in any case the great men were also deeply interested in this subject and contributed to it. He naturally starts with Creation and notes, quoting Scripture with some modesty, that it was only on the third day that “[t]he Lord God planted a Garden eastward in Eden, and there he the Man whom he had form’d”. Of its “Mathematical Distribution” Switzer ventures no guess, but asserts that after the Flood, probably somewhere near Armenia, Noah “began to be a Husbandman, and he Planted a Vineyard” (IR I 5). Thus, Scripture attests the founding of humankind’s history of gardening, and, by Switzer’s adoption of Zoroaster actually being one of the sons of Noah, this is confirmed in one of Switzer’s most trusted non-Biblical ancient sources, Pliny the Elder’s Natural History.

Thus, Switzer’s ideas are founded in Scripture and the classics, and he uses them freely to trace the early part of his narrative. For the second part he relies rather more on the poetry of the 17th century, that of Browne, Cowley, Milton and Temple. These are selected to further his own attitudes and give strength and colour to his opinions. Then the substantial last part of his history traces his own knowledge of the period following the Glorious Revolution and paints a rather Whiggish and progressive account of the making of the great gardens of Longleat, Chatsworth and Badminton up to the death of the Duchess of Beaufort there in the spring of 1715.

For Switzer the Biblical ancients, having been driven out of Paradise, worked slowly and with much toil, “living a Pastoral Life in open Fields and moveable Tents … Gard’ning was doubtless little known or practis’d by them …” before David’s or Solomon’s time. But then Solomon “made me Gardens and Orchards, and planted Trees in them of all kinds of Fruit; I made me Pools of Water, to water therewith the Wood that bringeth forth Trees” (IR I 6). The earliest description of a garden in classical sources is roughly contemporary, found in Homer’s long passage about Alcinous, and there he gives a trifle more detail but shows the same kind of garden. A well-watered enclosed ground of some four acres adjacent to the house is planted with lofty fruit trees … apple, pear, pomegranate, fig and olive with grapes from “order’d Vines in equal Ranks appear,” while “Beds of all various Herbs for ever Green, in beauteous Order terminate the Scene.” As a perfect idea few can surpass this, and doubtless this has remained the ideal well into modern times. The Villa d’Este at Tivoli from the 1540s and the Botanic Garden at Oxford, about a century later, are of similar size and composition.

For the more extensive plantations Switzer looks to the elder Pliny’s account of Epicurus (341–270 BC), who was “the first that brought into Athens the custom of having, under the name of Hortus, a Garden, the Delights of Fields and country mansions … and hence we may conjecture … that this was the Place which Pausanias reports to have been called, even in his Time, the Garden of Philosophy; adding that there was in it a Statue made by Alcemenes … and that the Temple of Venus did join to it” (IR I 12–13). Unusually, perhaps uniquely, for Switzer, the tillage and dressing of land, and agriculture in its developed forms, are allied to gardening and his History. The Romans’ “great Veneration for Gard’ning, Agriculture, &c …” is almost sufficient in itself. And as gardens had provided a home for philosophy, so Switzer believes that early Romans dwelt communally in gardens (IR I 19), but unlike the more arid wilderness of their Biblical neighbours, the Latin countryside was “the nearest Resemblance to Heaven that could possibly be found on Earth …”, as Vitruvius also asserted. Switzer cites Aeneas’ visit to Elysium with the Sybil, when on enquiring of his father where the Blissful lived he was told, “… In no fix’d Place the happy Souls abide; In Groves we live, and lie on mossie Beds, By Chrystal Streams that murmur’d thro’ the Meads” (Dryden, quoted in IR I 20). Not only did he draw from Virgil notions of the countryside as Paradise, but he could populate its imagined scenes with characters and stories, especially of the shepherds and ploughmen familiar to his own country experience, and could even find “as to the Designing Part” the arrangement of trees in “Quadratic and Quincuncial Form” in the Georgics. Virgil’s works and life seem to provide the very pattern for his Ichnographia Rustica, and thus he cited these higher realms of poetry, greatly esteemed as they were in the late 17th century, as his foundation.

Few treatises specifically on country life and farming had survived from classical times. But this handful of sources indicated to Switzer the very high standard of knowledge, practice and even philosophical attitude of the ancient Romans. These tracts had the same literary aspirations and qualities set by the poetry. The oldest of these is Marcus Porcius Cato’s De Agricultura. Cato (234–149 BC) was a venerated Roman of the old school, that is, the Republican period. He was a soldier, and a most resolute one; he disliked luxury and had little time for the idea of nobility. His surname meant “the shrewd”, and his interest in farming was lifelong and included what is now sometimes called agribusiness, and on a very large scale. An old farmer from the Sabine country, he embodied the most esteemed Roman virtues. He took his oratory seriously and worked on his speeches and wrote them out for improvement. His literary output was great and ranged to witty aphorisms but consisted mostly of history, ethnology and antiquities. All of that is lost; only the De Agricultura, incidentally the earliest composition of Latin prose, survives, and it is looser and less polished than he would have approved of.

Switzer found in Cato two qualities very congenial to his argument: the character of the farmer, and the pattern of the farm. For these really form the basis of Ichnographia Rustica. According to Cato, who relays it as information well known rather than his particular opinion, “… it is from the tillers of the soil that spring the best citizens, the staunchest soldiers; and theirs are the enduring rewards which are most grateful and least envied. Such as devote themselves to that pursuit are least of all given to evil counsels.” He is drawn to commerce, but that career is full of risks and pitfalls. For Cato banking too has its great rewards, if honestly pursued, but he observes that is most unlikely to happen. The farmer’s life is best, for himself and for Rome.

His ideal farm will face south, be backed by hills, be in a flourishing country near a good sized town and be at the sea-side, or on a navigable river. Frugality is all. “Know that with a farm, as with a man, however productive it may be, if it has the spending habit, not much will be left over.” The best disposition of a farm for Cato has a vineyard (if it promises good yields), an irrigated garden, an osier bed, an olive orchard, a meadow, a cornfield, a wood, a cultivated orchard and a mast grove. This estate will consist of about 66 acres and may be all there is. It will always act as home-place, home-farm or mains. Planting should come first, and if it succeeds then, in his middle age, a farmer can begin to build, according to his means and always furnished for a country life. Such a place will be attractive; the owner will visit often and find fewer mistakes and better crops. “The face of master is good for the land.” The roadways and field divisions should be planted with elms, and near the house is the place for the cultivated orchard, as also a “garden with garland flowers and vegetables of all kinds, and set about with myrtle hedges …” This is also the pattern of a Switzer garden.

A farm in Latin is villa and of course refers to the whole. In Switzer’s time villa was used to describe a small house only but one of some distinction because of its design, contents or setting. This is also after ancient usage, and by the time of Marcus Terentius Varro (116–27 BC) villa was being used in this sense too. Varro was another polymath and public figure. He backed Pompey in the civil wars that ended the Republic. Julius Caesar restored his property to him, but then Mark Antony had him proscribed: so he spent his last years in forced retirement, in study and writing. His literary works were numerous and distinguished. His Nine Books of Disciplines about the liberal arts established that very significant grouping, and also the notion of encyclopaedic knowledge later taken up by Pliny. They covered a very wide range, from belles lettres, essentially poetry, to works about history and antiquities, and various technical works about how to do things, which includes his only work that has survived in full, Rerum Rusticarum Libri Tres, which he wrote in old age.

Varro’s text is strikingly modern when compared to Cato’s declarative statements of what one ought to know about farming. Varro uses the form of dialogue, sometimes several voices, and enjoys all sorts of discursive, and also enlightening, departures. He has enough of the old Romans’ contempt for the foolish excesses of fashion. Naturally he recognizes, and to a degree deprecates, the modern form of the villa with its expensive furnishings and decorations, and often complete lack of the agricultural aspect. Rather than build “according to the thrift of the ancients than the luxury of the moderns … the effort is to have as large and handsome a dwelling-house as possible; and they vie with the ‘farm-houses’ of Metelus and Lucullus, which they have built to the great damage of the state” (Varro, book 1, chap 13). But it is an almost formal condemnation and without real sting. This becomes clear when he gets to the heart of his matter, which is that a farm, and by extension any kind of villa, ought to make money. So he extols those near Rome which cater to the luxury trade. The subject of book 3, Of Poultry, Fish and Dormice, indicates just how lucrative preparing these delicacies for the Romans could be, and in his description of his own Ornithon (book 3, chap 5, p 447 et seq) Varro gives hints that Switzer very likely followed in his forays into the design of menageries, and perhaps more widely (see below). And although Varro, probably to discredit Cato’s authority, misreads his intentions in the description of the standard farm, Varro also tells of the kinds of divisions of fields used by the Romans, which Switzer finds very helpful. One suspects Switzer also found Varro’s style of writing congenial, and followed it rather more than that of Cato.

With Lucius J M Columella (AD 4–70) comes the definitive treatise on Roman husbandry. It provides the pattern for all subsequent work before modern times, and itself appeared in a scholarly and substantial quarto edition in London in 1745. Sadly, its translator remains anonymous. Switzer recognized the value of Columella’s De Re Rustica, and found references there for his history as well as justification for his arguments for Rural and Extensive Gardening. Columella lived and wrote in the post-Augustan age, when the old Roman virtues had been supplanted by some of its greatest vices: still he upholds the former while acknowledging the luxury of his time. In his section on the disposition of a villa, the Manor House of the 1745 translation, we find the first modern understanding of how a villa, or any Roman house, was designed – or, it should be said, early evidence of the great misunderstanding which had bedevilled architects and designers from the 16th century, which was the confusion that a great number of rooms signified palatial standards. As the translator puts it in his note: “… as their riches and luxury increased, they became much more magnificent; and a sumptuous and magnificent villa seems to have been the darling even of the wisest and most moderate among them … and when those of private persons were so stately, what must those of the more eminent station have been, as that of Maecenas, Lucullus, Cicero &c. As for those of the Caesars …” (Columella 31, see also 338). That these many rooms were really no more than closets never occurred to them, but the core problem of the appropriate manner in which to live for those with wealth and power, as well as the aspirations of those with neither, remained Switzer’s concern and also the concern of his time.

Columella accepts the principal divisions of the villa grounds, as presumably also their size of roughly 60 acres each, and structures his text accordingly. For Switzer, apart from his various assertions that vineyards in parts of England produce very good wine, the very significant portion of Columella about Trees, which is always an aspect of the production of wine, is rather passed over, whereas the treatment of the tillage part, the Meadow and to a slightly lesser extent the livestock parts, the Park or Coney-ground, becomes central to his idea of a garden and to his work in improvement more generally. Once the idea is established that a Meadow or Park is integral to the design of Rural and Extensive Gardens, then to read these chapters (Columella 95 et seq) is to encounter the same concerns as those of the improvers of the 1730s.

Columella’s treatment of the Garden assumes enclosed grounds as described in Homer and Cato, but with the vineyard and productive groves for olives (which he calls the Palladian berry) removed, and he concentrates on the finer vegetation. He carries on where Virgil, sadly for lack of time, had declined to continue and casts his remarks in verse in imitation. This tenth book (Columella 417 et seq) the translator renders in blank verse. This is followed, in book 11, chapter 3 “as the culture of gardens and of garden-herbs, in prose” for the benefit of the unpoetical bailiff. With significant exceptions Switzer’s treatment of the Kitchen garden, and also occasionally the Fruit garden, as an enclosed place with its own nature and rules, but within easy reach and in correspondence with the rest of what he came to call a Rural and Extensive scheme, follows his understanding of Roman practice as well as the best modern (late 17th to early 18th century) good sense.

Like any historian Switzer has to follow his sources, but some are more congenial and richer than others. Some greats are, surprisingly, given short shrift. Vitruvius Polio, despite his “excellent Directions relating to Situations”, warrants only a paragraph, not because he is obscure, but because “[t]hese are quoted by most Authors that treat of Gard’ning, at the Beginning of their Books; for which Reason I shall content myself, after I have paid this short, but willing, Tribute to the Memory of this great Architect and Gard’ner, and proceed to [new paragraph] Horace the next in my List of Garden Heroes …” (IR I 28). Unlike the ideal historian Switzer is not so much wishing to present a clear and true account of past events as he is seeking to find justification among the acknowledged greats for his particular vision of how best to make big gardens in early 18th century Britain, of landscape scale, but as yet without a settled name. In Horace he finds justification for a preference for the country instead of the capital in his long quotation from Thomas Creech’s translation of the Epistles. As evidence it brings allusion, and some colour perhaps, but little “information”. Thus, it is sufficient to Switzer to enumerate evidence of the fondness the great men of Rome had for their farms and gardens, and for the countryside generally, and the disdain for the business, intrigues and follies of cities, to which they resorted only because of duty.

His treatment of modern great men is also brief, although his choices are most apt. The Cardinal of Ferrara at the Villa d’Este at Tivoli, and the Pope at the Villa Belvidere (Aldobrandini) at Frascati are noted as creators of great works, “[b]ut the more useful Part of my Subject, I mean Agriculture, Planting &c have not appear’d with that Lustre as it had formerly done in those Countries and the Reasons of it are drawn from the Despotick Power and Pride of the Roman Church” (IR I 38).

Switzer’s readers may therefore conclude that while they are being encouraged to admire the Villa d’Este, and perhaps to emulate some of its beauties, they are being addressed by a good Englishman of suitably Anglican persuasions. When he comes to praise Louis XIV he is equally clear. As one of the greatest characters yet produced he made a masterpiece at Versailles,...