![]()

Chapter 1

Defining Religious and Faith-Based Organizations: and Defining Them as Voluntary Organizations

Religious and faith-based organizations form a sizeable proportion of organizations in the UK and other European countries, and possibly an even larger proportion in the USA; they make a distinctive contribution to civil society; and they are now particularly important for the part they will play in enabling people of different faiths and of different ethnic groups to relate to one another and to society as a whole. It is therefore vital that such organizations should be studied and understood – and, if we are to study organizations in the category ‘religious and faith-based organizations’, it is important to know which organizations are in that category and which are not.

A subsequent question which I shall tackle is that of the relationship between definitions of ‘voluntary organization’, ‘religious organization’ and ‘faith-based organization’. It is important to do this because the ways in which we define and study religious and faith-based organizations will depend largely on how we answer the question: Do religious and faith-based organizations belong to the voluntary sector?

Two Ways of Defining

Ludwig Wittgenstein suggested the image of ‘family resemblances’ to describe the relationship between one use of a word and another (Wittgenstein 1967: §§ 66f.). To suggest a core definition of a word is simply to add yet another member to the existing ‘family’ of meanings. This rather suggests that we shall never formulate a tight definition of ‘religious organization’, ‘faith-based organization’ or ‘voluntary organization’, as whenever we use these terms in new contexts they take on new meanings and new connections with other words. But we do need to try to define categories for the purely practical reason that it is helpful to generalize and we need to know what we can generalize to and what we can generalize from. If we want to know how to manage better a particular organization then we shall seek out other organizations which we can label as the same type of organization. This requires categorization, and it requires definitions of categories.

The ‘classical’ way of defining a category is to propose a list of characteristics. Those entities which possess the characteristics are in the category, and those entities which do not are not: so a square is a rectangle because it has four sides and opposite sides are parallel. But for anything other than simple cases of definition this strategy quickly breaks down because there are frequently cases where we cannot determine whether the entity concerned is in the category or not. Thus, if to be a ‘bird’ something needs to fly, then an ostrich is not a bird and a bat is.

Eleanor Rosch (Rosch and Lloyd 1978; Rosch 1999) has suggested that categories are not the clear-cut things we often think they are, and that it is often not the case that entities are either in the category or not in it; and neither is it the case that entities belong equally. Thus a robin is more a bird than an ostrich is, and a bat is on the boundary of the category.

Rosch points out that in the real world we define categories in terms of prototypes and then decide whether something is in the category by asking how similar it is to the prototype. Mark Johnson (Johnson 1993) has successfully used this means of definition to give a coherent account of how we categorize actions as moral or otherwise: we have in our minds a prototype lie and we then ask whether other actions are more or less like it; and (of particular interest to us) Anthony Freeman (Freeman 2002) has employed the same method to define ‘Church’.

Defining Religious Organizations

The first problem we face when defining ‘religious organization’ is a problem with the definition of ‘religion’.

Durkheim defines religion as ‘a unified system of beliefs and practices relative to sacred things, that is to say, things set apart and forbidden – beliefs and practices which unite into one single moral community called a Church all those who adhere to them’. A ‘Church’ is essential to the definition because religion is ‘a collective thing’ (Durkheim 1915: 47) which connects practices and ideas together ‘to classify them and systematize them’ (ibid.: 429). Geertz suggests a similar definition:

Religion is 1) a system of symbols which acts to 2) establish powerful, pervasive, and long-lasting moods and motivations in [people] by 3) formulating conceptions of a general order of existence and 4) clothing these conceptions with such an aura of factuality that 5) the moods and motivations seem uniquely realistic. (Geertz 1975: 90)

In his The Oxford Dictionary of World Religions, John Bowker (1997: xv) lists a variety of definitions of religion, suggests that ‘we can recognize a religion when we see one because we know what the many characteristics of religion are; but we would not expect to find any religion which exhibited all the characteristics without exception’ (ibid.: xxiv) and follows that with: ‘Religion is a risk of intolerance, cruelty, bigotry, social oppression and self-opinionated nastiness’ (ibid.: xxiv). David Ray Griffin suggests this: A ‘full-fledged religion’ is ‘a complex set of beliefs, stories, traditions, emotions, attitudes, dispositions, institutions, artistic creations, and practices – both cultic and ethical, both communal and individual – oriented around the desire to be in harmony with an ultimate reality that is understood to be holy and thereby to provide life with meaning’ (Griffin 2001: 12). The introduction of a bibliography on Managing Religious and Faith-based Organisations (Harris and Torry 2000) begins: ‘This Guide has its origins in our own quest for research-based literature which could help us to understand the organization and management issues faced by religious and faith-based organizations – primarily congregations, denominations and religious-based voluntary and non-profit organizations.’ So is a for-profit Christian radio station a religious or faith-based organization? On Griffin’s definition: is humanism a religion? And Marxism? And National Socialism?

For any definition based on a list of characteristics, there will be people who will disagree with the list, there will be entities we might want in the category but which don’t fit the criteria, and in this case there will be entities which do fit the criteria but which we might not wish to call a ‘religion’.

A second problem with defining religious organizations is that the notion of ‘religious’ is not related to the notion of ‘religion’ in any clear-cut way. An attitude or an action might be thought ‘religious’ without being related to any particular religion; and religions frequently give rise to actions and attitudes which we might not wish to call ‘religious’.

A third problem is that we have to choose whether a ‘religious organization’ is to be defined as an organization related to a religion or as an organization which has religious characteristics: and the lists of characteristics of these two kinds of organization will be different. (A meditation group might be a religious organization on the latter basis but not on the former).

A fourth problem related to the classical method of definition is that we shall have to decide how many ‘religious’ or ‘religion’ characteristics an organization will need to have if it is to be counted as a religious organization. The fewer characteristics we require the more organizations will be religious organizations; but the more we employ the more we shall be sure that there will be little controversy over whether the organizations picked out by the characteristics are in fact religious organizations.

It might be better to do what we do in fact do, and pick a prototype. Christian congregations, synagogues, Sikh and Hindu temples, and mosques, are religious organizations (and Jeavons is right to suggest that they are the only unambiguously religious organizations; Jeavons 1998). So the British Humanist Association might be a religious organization, and Tate and Lyle is not one. By comparing other organizations with those organizations which are undeniably ‘religious organizations’ (with the two words always taken together, as religious organizations might not always be religious on the basis of some definitions of that word) we can decide whether they are at the centre of the category, whether they are to some extent religious organizations, whether they belong on the boundary of the category, or whether they are not religious organizations at all. By doing this we shall be doing what Peter Clarke and Peter Byrne invite us to do and operate a ‘family resemblance’ strategy for defining religion and religious organizations (Clarke and Byrne 1993).

I suggested that the first problem we face when defining ‘religious organization’ is the definition of ‘religion’. An alternative strategy is suggested by the mention of institutions and practices in Durkheim’s and Griffin’s definitions of religion, by Alata’s definition of religion as a ‘way of life’ (Alata 1977) and by Bruce’s decision to ignore inner spiritual states because they are so difficult to study and instead to define religion in terms of individual and group behaviour (Bruce 1995: vii). In the same way, we could define religion in terms of institutions and their members’ activity, thus obviating the need to define ‘religion’ at all because religion then becomes religious organizations and their memberships.

Defining Faith-Based Organizations

We experience the same problems with faith-based organizations as we experienced employing the classical method of definition with religious organizations. By ‘faith’ we might mean either a particular ‘Faith’ or a faithful attitude of some kind; and we shall then need to ask to what extent an organization is influenced by that Faith or that faith. For an organization to be ‘based’ on a faith could mean either that a particular Faith or kind of faithfulness provides some of its values, or we might mean that it is closely governed by that Faith’s religious organizations.

But a problem we face when we attempt to employ a ‘prototype’ definition is that ‘faith-based organization’ is relatively recent terminology which was specifically invented to denote organizations influenced by Faith-traditions but not to the extent of being religious organizations: that is, a religious organization’s main purpose is religion (although we might have cause to question this once we begin to discuss the sociology of religious organizations) and a faith-based organization has another main purpose but is strongly influenced by a religious tradition or by a religious organization. The recent genesis of the terminology means that it is not easy to pick a prototype or prototypes, as the choice of a prototype relies on a history of custom and practice; and the history of this particular terminology means that a definition in terms of characteristics is imposed on us from the beginning and to seek other means of definition will not be to define correctly or usefully.

The only solution is to employ both methods of definition, with the classical definition suggesting prototypes, and the prototypes then being used to decide which other organizations we admit to the category and to what degree we admit them – with our decisions always being tested against the classical definition of the category.

A Church of England school is thus a faith-based organization, as its main purpose is education but it is significantly influenced by the Christian tradition; and a Christian radio station might be a religious organization or a faith-based organization – but probably not both, as the definition of a faith-based organization as an organization the main purpose of which is not religion is likely to preclude a faith-based organization from being a religious organization (though not necessarily, of course, if we employ the prototype method of definition for religious organizations and not a strict list of criteria which includes the criterion that an organization is a religious organization only if its main purpose is religion). The South London Industrial Mission (SLIM) is supported by Churches and its staff are mainly clergy, but only careful examination of its activity could decide whether it is a religious or a faith-based organization. (We cannot discuss motivation very easily as only observed behaviour is available to us.) SLIM has done, and still does, education, networking, pastoral care and welfare work. It does very little worship, prayer or evangelism. It might be faith-based in the sense of faith-influenced, but it is not religious. (It might also be closer to the Kingdom of God than many religious organizations, but that is a different debate.)

Of interest on the boundary between faith-based organizations and other organizations are faith-based organizations which are becoming secularized (Demerath et al. 1998: part V; Stone and Wood 1997) – a process which Swartz sees as inevitable (Swartz 1998), but which is never complete, because differences remain between organizations which were once faith-based and those which never were (Cormode 1998; Grønbjerg and Nelson 1998). Thus an industrial mission which takes on more and more secular activities does not necessarily become secular if its motivation and support-structures remain church-based (Torry 1990); and a Jewish elderly care home which has few Jewish staff is never entirely secular (Harris 1997).

So: a housing association recently founded by a group of churches is likely to be a faith-based organization; a housing association founded some time ago by a group of churches might or might not be a faith-based organization; and neither a congregation nor British Airways is a faith-based organization.

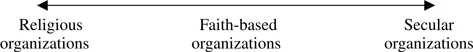

It might be that the best way to envisage the situation is as a spectrum, with religious organizations at one end and secular organizations at the other. Faith-based organizations will then be found between the two end-points, either nearer to the ‘secular’ end, or nearer to the ‘religious’ end, or somewhere in the middle (see Figure 1.1):

Figure 1.1 A spectrum of organizations

Thus we shall expect faith-based organizations to have some characteristics like those of religious organizations, and some characteristics like those of secular organizations. We might locate a Church of England Voluntary Aided School nearer to the ‘religious’ end of the spectrum than a Voluntary Controlled School, because in the former case the parish and the Diocesan Board of Education provide more governors than in the latter case; but both will be quite close to the ‘secular’ end, because the local education authority pays the staff and the government sets the curriculum. And there will be movement along the spectrum: a housing association might start off quite close to the ‘religious’ end, and might then slowly (or maybe even rapidly) migrate towards the secular end as it relates more closely to secular bodies and consequ...