![]()

PART I

Performing Medieval Quacks

![]()

Chapter 1

Quack Actresses of 15141

The quacks of early modern music, art and literature are so numerous not least because their precedents are so venerable. Their dramatic origins go back many centuries and quacks, themselves significant promoters of stage spectacle, are the earliest non-biblical characters in religious drama, where they make an increasing contribution from the twelfth century onwards. Most often, they feature on the religious stage during the Visitatio sepulchri, or visit of the three Marys to the tomb of Christ. Here an itinerant pedlar, variously characterized as a mastickár, medicus, mercator or unguentarius, with or without a wife and troupe, sometimes sells the Marys herbs and spices before they go to embalm Christ's body and discover the empty tomb. The pivotal scene of medieval Easter observances and Passion performances, widely regarded as crucial to the emergence of religious theatre from church ceremony, the Visitatio sepulchri and its so-called merchant scene have attracted considerable scholarly attention.

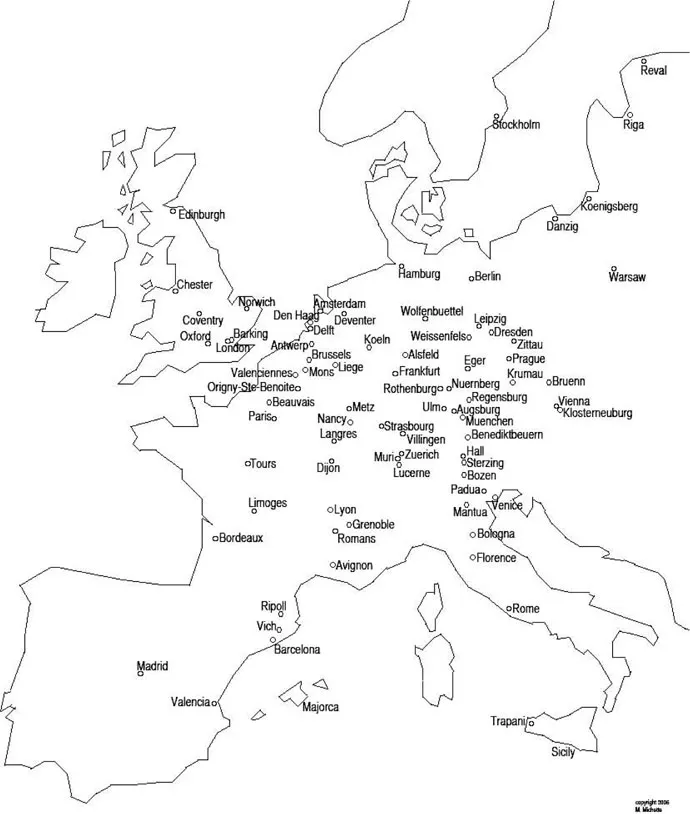

The amateur performers of religious plays, drawn from their sponsoring church congregations, were overwhelmingly male. This tradition of all-male casting was spectacularly breached in 1514, when actresses were cast in virtually all the female roles of an exceptional production of the Bozen Passion Play. Bozen, now the north Italian town of Bolzano, was then a major German-speaking South Tyrolean trading centre, sharing prominence with neighbouring Sterzing (now Vipiteno, in the Italian Tyrol) immediately south of the commercially important Alpine Brenner Pass trade route. Its community-sponsored Passion Cycle, one of the largest in the German-speaking regions, was a frequent, sometimes annual, showcase not just for its piety, but also for its economic success. Acted by local amateurs, the 1514 production had well over a hundred named roles. Women were cast in around twenty female roles, many shared with an actor or second actress (Diagram 2). It has been suggested that this pattern of casting is a possible indication that the decision to put women on the stage was taken only when rehearsals were well under way, and most of the female roles had, as was then customary, already been assigned to men.2 A more mundane possibility is that multiple casting was undertaken as a sensible precaution, given the strenuous demands of a one-week production and the unpredictability of pregnancy. The only named female roles in which women were not cast for this production were those of the Virgin Mary and Maria Jacobi (the evidently still beardless Cristofferus Rotnpuecher), Mary Salome (Cristofferus Scuto), and the damned souls of a bawd, a sorceress and a maid (Sigmundus, Johannes and Martine Scuto). Anna and Endl, two servants of the Furst family, took the roles of Mary Cleophe and secunda ancilla, while prima ancilla was played by Els, probably the wife of Oswalt Schlosser (Septimus Ruffo). The wives of Hans Breiolt (Pilate) and Hans Kramer (Pater Ceci) played their stage wives. The Kramer's daughter Endl played the Canaanite daughter. The daughter of the innkeeper Jorg Ruster (Nicodemus and Abraham) played Mary Cleophe. Ludl Jan Goltschmid, sister of Jochum Goltschmid (St John), was cast in three roles, the Caananite wife, the adulteress, and Eve to Wolfgang Furst's Adam. An unnamed Goltschmid sister shared the role of Mary Magdalene with Madlen of Lindau, a daughter of the stonemason Fricz Flaser (or Glaser), the maid of Wolfgang Furst and Gretl Federl of Krems. The wife of the miller (Primus Zaduceus) and daughter of Plasy Pader between them took four further roles, discussed below. These fifteen or so women, virtually all family or household members of the play's actors, represent one of the most significant groups of documented actresses of their time, unprecedented on the pre-seventeenth-century German-speaking stage.3

The rare records of actresses in religious and civic performances suggest a less peripheral female contribution than that reflected by the secondary literature, and confirm the religious stage as a potential training ground for early professional female performers.4 Women were forbidden from speaking inside the medieval church, but by the thirteenth century, some were being cast in non-speaking roles of religious dramatic ceremonies, as when a girl from Beauvais played the Virgin Mary in the town's Epiphany festival. The young unmarried women of Deventer were rewarded for contributing, in an unspecified capacity, to a fourteenth-century municipal production, and the married townswomen of Chester regularly participated in late fifteenth- and early sixteenth-century productions of the city's Assumption of the Virgin. Certainly in the late fifteenth century, the wives of members of the confraternity that staged the Lucerne Passion could enrol without additional charge; whether as players is unclear, although a sixteenth-century Swiss production of Judith featured actresses. One performance in particular of the Metz Mystère de Sainte Catherine generated copious documentation, whose details are variously reported in the secondary literature. In 1468 or 1486, the eighteen-yearold daughter of a local furrier or glazier named Dédiet was applauded for her resounding success in the demanding 2,300-line title role, immediately following which she retired from the stage to marry a noble mercenary, Henri de Latour. Less is known about Waudru de le Nerle, who played the young Mary in the 1501 Mons Passion, the girl in the title role of the Nancy St Barbe staged for the Duke of Burgundy in 1506, and the four, possibly five, girls cast in the 1547 Valenciennes Passion. The Spanish sixteenth-century religious stage was even more liberal than the French in casting actresses, and their private lives were the source of much scandalous gossip. Anna Bechimerin acted Mary in a 1519 Basle school production of an Epiphany play, and an adult woman, Françoise Buatier, played the Virgin in the 1535 Grenoble Passion. The widowed former schoolmistress Barbara Frölichin became the first known woman director on 6 April 1578, when she directed a play in the Council Chamber of Sterzing's town hall, perhaps acted by schoolgirls.5 In a letter of December 1582 to the devoutly Protestant Magdalena Behaim (1555–1642), her husband, a Nuremberg cloth merchant then in Lucca on business, notes his enthusiasm for mixed-gender commedia dell'arte performances, adding ‘but they are not to be compared with your plays in St Martha and the monastery’.6 This brief comment alerts us to a whole sphere of German religious theatrical practice, in which women such as Behaim evidently played a full role, of which we know very little.

The plays of European convents, where amateur all-female acting had a venerable tradition, often demonstrated surprisingly free early use of the vernacular, perhaps intended to facilitate the participation of women. Fourteenth-century examples include versions of the Visitatio sepulchri from Prague's St George Convent, and the Ludus paschalis of Origny St Benoîte (where, already in the thirteenth century, some nuns took performative roles in Easter ceremonies, and another represented God). Both convents included the merchant scene, and it seems that nuns were significant in popularizing this early example of onstage shopping. Tertiaries, novices, nuns, canonesses or abbesses are thought to have played the three Marys or other female roles in convent plays in, for example, Brescia, Eisenach, Essen, Florence, Huy near Liège, Majorca, Prato and Troyes. Specialists are divided on whether Hrotsvitha of Gandersheim's Terence-inspired late tenth-century passions of the saints were performed, or even written for performance. However, many believe that Hildegard of Bingen may have participated in a twelfth-century mixed-gender staging of Ordo Virtutum at her convent. Katherine of Sutton, abbess of Barking, wrote and produced a Visitatio and other Latin dramatic ceremonies performed by mixed-gender casts at the Easter services of her convent during the period 1363–1376. By the late fifteenth century, Italian convents routinely fostered a flourishing theatrical tradition, staging sacre rappresentazioni sometimes written by women, often focusing on female saints, and increasingly acted solely by the convents’ own novices and schoolgirls. But success attracted powerful opposition. By the seventeenth century, the combined efforts of the judiciary and clergy had all but stamped out this six-century tradition of women's theatrical practice.

Only exceptionally outside convent plays are women systematically cast in the majority of female roles of a production. The suggested contributing factors include the ravages of two plague years (Thévenot's 1509 Romans Le Mystère des Trois Doms, and perhaps also the 1510 Châteaudun-sur-Loire Passion) and the Bolzano church's exceptional indoor acoustics (Raber's 1514 Bozen Passion). Thévenot and Raber's occupations may have played a part in their decisions to stage mixed-gender productions. Appointed by, rather than primarily belonging to, the male-dominated hierarchies of church, guild or civic administration generally responsible for religious plays, both were professional painters, whose approach to their official briefs would have been informed by a heightened sense of the visual.7 Its sheer expense, in terms of additional costumes, rehearsal time and suchlike, would have discouraged any but the richest communities, such as Bozen, from pursuing multiple casting as a blanket strategy. Quite apart from obvious considerations such as the demands of childbearing and routine domestic duties, issues of stamina, and religiously motivated resistance to female participation, perhaps the most crucial block to casting women is the educational factor. As Gilder points out, many girls were incapable of reading scripts.8 They were rarely taught Latin or rhetoric, and, outside the convent system, suffered systematic exclusion from the rigorous church-sponsored musical training available to gifted boys of whatever social class. Even so, women's generally weaker and less trained voices did not always exclude them from outdoor performances. The 1547 Valenciennes Passion was an outdoor production. Also in the 1540s, Felix Platter watched a cast including the daughters of Sebastian Lepusculus act Heinrich Pantaleon's product...