![]()

1 Introduction

Every day, somewhere in the world, events occur which could have been prevented if the participants had been better trained. Take these examples, for instance. In October 1994, a Boeing 747 took off from Sydney Airport bound for Japan.1 An hour after take-off an engine had to be shut down and the crew decided to return to Sydney. On final approach, the aircraft's nose-wheel failed to lower and the aircraft touched down with no nose gear. The investigation revealed deficiencies in the competence of the Flight Engineer as well as serious mismanagement of the crew training associated with the introduction the aircraft into service The flight was the inaugural long-haul route for the company concerned, a factor which contributed to the situation.

In September 1997 a member of the cabin crew aboard an MD-80 aircraft was approached by a ground handling agent who asked about a toilet door that needed fixing.2 The in-bound crew had reported the door faulty but, having just boarded the aircraft herself, she was unaware of the problem. The agent talked about the toilet in the First Class section needing some WD-40 lubricant. 'They didn't have WD-40', he said 'but I found something just as good'. The job done, the cabin crew member commented on the strong smell and the agent replied that he 'had only used a little'. After take-off, 2 of the cabin crew and one passenger fell ill and needed hospitalisation, which resulted in the aircraft being diverted. The passenger handling agent was an office manager, not a technician, and his substitute for WD-40 was a highly-toxic lubricant which was not to be used in confined spaces, a fact clearly marked on the container.

In June 1998 a 747 taking off from San Francisco, again bound for Japan, experienced problems with an engine soon after rotation.3 The First Officer (FO), who was flying the aircraft, applied the wrong technique to keep the aircraft under control. The aircraft lost speed sufficient for the stall warning stick shaker to be activated. The aircraft cleared San Bruno Mountain, 5 miles northeast of the airfield, by 100 feet, missing the radio masts rising a further 600 feet above the mountain top. The subsequent investigation found that most FOs rarely handled the controls on take-off and landing. In fact, some were flying for up to 2 years without touching the controls during these critical stages of flight, other than in the simulator. Furthermore, the airline discovered that FOs were regularly letting their currency lapse in order to gain extra holiday, given that they could not fly between losing currency and completing a simulator re-qualification.

These 3 case studies may raise a few eyebrows but each highlights a problem which most aviation professionals encounter everyday. In order to keep the schedule operating we have to be flexible. So, the office manager who picked up a can of lubricant was only trying to help. That said, we need to consider the way in which the company identified the skills needed of its workers. Perhaps a qualified engineer was not required but we can examine the approach to health and safety training, product knowledge and the identification of hazardous materials. The Flight Engineer on the 747 had a history of training problems but he was not helped by the situation he found himself in. Inter-airline rivalry and over-stretched management degraded the training intended prior to the introduction of the 747. Now commercial pressures have intervened although selection methods, course graduation standards and overall project management are all implicated.

The final example, again involving a long-haul aircraft, reveals some of the problems associated with maintaining skills in an environment that offers little opportunity to put training into practice. The last example also shows up another aspect of aviation that will be addressed in Chapter 1. Aviation, like all economic activity, involves individuals, all of whom have their own agenda. The FOs in this airline had developed a scheme to augment their days off, at the company's expense. Work can be seen as a constant struggle to balance a set of diverse needs, including the motivation of the workforce. This struggle can have an impact on training.

Ironically, training has a long tradition in aviation. Such was the difficulty of mastering early flying machines that the need to train was well-established from the beginning. Aviation training devices have been at the forefront of technology; solid-state electronics were widely used in the design of flight simulators long before they were commonly found in aircraft. Add to this the regulatory requirements which mandate a need for regular refresher training and we have a climate in which the need to train is unquestioned. However, that is not to say that all training in the aviation community is high quality, or that all those in need of training get what they require. Rising accident rates, increasing pressure on budgets, deregulation and privatisation are all forcing a re-examination of the time and resources devoted to training in the industry. And despite the benevolent attitude alluded to earlier, it is probably fair to say that many aircraft operators only do the absolute minimum training necessary in order to remain legal, and they probably do not even do that very well.

With the spread of new technology on the flight-deck, the increasing emphasis on revenue management, the inexorable drive to extract even more work out of reduced staff numbers, it is timely that we re-examine the role of training design in meeting some of these operational goals.

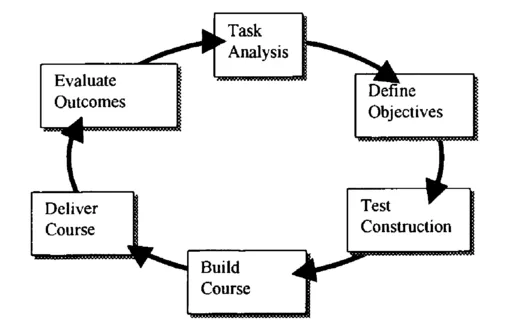

Figure 1.1

The Training Design Cycle

This book is aimed at airline personnel who have a responsibility for the design and management of training. It assumes that the reader will have some experience of delivering training. It is not intended as a guide to the production of classroom materials, there are better books available on developing the various types of training material. Equally, this book is not about how to deliver training in a classroom. The main aim is to broaden the reader's understanding of training as an activity and some of the problems associated with training design generally. We will discuss methods and techniques and offer suggestions as to how to solve training design problems. However, our main objective is to reflect an idea of what constitutes best practice in terms of training design.

The book is arranged along the lines of a classical model of training design with a chapter devoted to each stage of the model. Our intention is to broaden managers' and training designers' understanding of the process. We will discuss the key issues surrounding each topic and suggest methods to be used at each stage. We will highlight weaknesses in current approaches to training and, with one eye on the future, outline strategies that will prevent the reoccurrence of the incidents with which we opened this Introduction. We end each chapter with a short exercise which will help you to consolidate what you have learnt.

![]()

2 Organisational Context

Introduction

Training design is, quite simply, the identification of a desired workplace performance which can be met by some form of training intervention and, subsequently, the design of a solution which can efficiently and effectively meet that need. Our aim must be to provide some form of guarantee of success but at an affordable cost; conversely, we cannot afford to waste money or run the risk of producing incompetent workers. Implicit in this goal is the assumption that training is the answer. This may not always be the case. Training is only one of many organisational processes; as we will discuss later, poor performance could reflect management practices, resource allocation or poor selection of personnel in the first place. Therefore, although our focus is clearly on performance in the workplace, we want to start this examination of training design practices in aviation by looking at the organisational context within which the activity takes place. At the end of this chapter you will:

- Have considered the economic, political, social and psychological factors that can influence training decisions.

- Have considered strategic reasons for poor workplace performance.

- Have considered a stakeholder analysis of training decision-making.

How to Guarantee Failure

As an introduction to this discussion of the organisational context, let us consider an example of how easily things can go wrong. A British airline invested in a ground breaking interactive video-based course designed to tackle management problems on the ramp. The hardware chosen as the platform for delivery was incompatible with the company's corporate Information Technology (IT) policy. In fact, when the project started, the company did not have a policy. By the time the interactive video course was complete, a policy had been agreed which had settled upon PC-based hardware as opposed to the AppleMac used in the project. Thus, from the outset there was no chance of maintenance or spares. Change processes in other parts of the company had an indirect impact on training strategy. So why didn't they redesign the package to run on acceptable hardware? In the early days of technology-based training, authoring packages were simply not exportable across different computer platforms. However, at much the same time the training department went through a reorganisation and the manager responsible for the project found himself out of favour with the new department head. The eventual outcome was that the training package was consigned to a cupboard. So, although an excellent solution to a very real and serious problem got several airings at conferences and exhibitions, its use in-company was short-lived.

This simple tale illustrates two of the dimensions by which we can define the organisational context; economics, in the sense of investment and pay back, and politics because training interventions can sometimes challenge perceptions of who is in control of decision-making. In addition to these, in this opening Chapter we will also need to consider the sociology and psychology of organisations as these will also influence any training solution we devise. Of course, none of these factors work in isolation within the workplace; in the real world, these four dimensions will be inter-linked. Nor are they present in every situation, after all, some training decisions are simple and straightforward; we should not overplay the hand at this stage! However, we have used them as a starting point because they are neatly summarise some of the key problems which have to be resolved before you even get down to the task in hand, which is to design training. Let us look at them in more detail, starting with economics.

The Economic Dimension

In the example we have just seen, the need of a large organisation to look for economies of scale by standardising on the computer technology used within the business outweighed the benefits of supporting a non-standard system just for one training application. The point here is that training has direct economic effects; it involves expenditure. More important, expenditure on training is usually seen in a negative context. It is difficult to show any direct return on the investment, Although the need for basic training to make staff productive is readily accepted, the scope of, say, induction training for improving staff retention and morale is rarely explored. To reinforce this failure to link training with a company's bottom line performance we need only cite the example of an airline which, once the monthly figures got too bad, shut down its training centre in an attempt to save money.

We can identify some of the direct economic inputs, such as: training staff costs, materials purchased, trainee costs, replacement costs in the workplace to make up for staff in training (or productivity lost as a result). There are also indirect effects. For example, raised skill levels may result in different expectations within the work force which, in turn, may require different reward schemes. We can, of course, identify some positive economic benefits of training, such as reduced error, faster turn-around, employment of new technology or working practices. It may be that more part-time workers can be employed or greater use made of outsourcing.

It is impossible, then, to think of training without also thinking of the costs involved. That said, surprisingly few airlines have budgets for training and fewer still actually know how much the activity costs them. One of the problems is that training often gets hidden, For example, some cargo or charter operators use empty positioning sectors to do pilot recurrent training. Given that the crew were required to fly the aircraft into position in the first place, the training is deemed to be free. Quite often, the scarcity of approved simulators for a specific aircraft type reinforces the view that it is cheaper to train on the aircraft. One UK operator of regional/commuter-sized aircraft ships its pilots to the US for refresher training in a simulator. The bill in 1998, given that an instructor from the airline was almost permanently based abroad, came to about half a million pounds. Again, some charter companies use line pilots to conduct Crew Resource Management (CRM) training during the off-peak season. Because there is no alternative use for these staff, the training is once more considered to be at no cost. In some cases, instructors prevail upon colleagues to give lectures as a favour. Quite often this is rationalised in terms of some perceived added benefit. For example, we know of some cabin safety trainers who had a pilot colleague deliver a short presentation on the theory of flight to new-hire cabin crew. Whilst laudable and, no doubt, of real benefit, it still represents unmanaged and uncosted training.

The real irony in all this is that, despite the fact that, in full-flight simulators, airlines employ some of the most expensive training devices in the world, training for staff other than flight-deck personnel is considerably under-resourced. Andersen Consulting,4 in a 1995 study reviewing airline training in the United States, found that carriers spent, on average, US$ 281 per year on cabin crew and US$ 3,565 on flight-deck training. Figures for a wide range of other US industries showed an average annual expenditure of US$ 800 - 1000 per employee. Using figures from the UK Civil Aviation Authority, again for 1995, we see that UK carriers fare little better. Whereas pilots attracted an expenditure of £3108 ($4972) per year, cabin crew training cost airlines from as little as £198 ($316) per head to as much as £1616 ($2585) per head. For comparison, UK industry as a whole spent an average of £384 ($614) per employee on training. An interesting point is the fact that scheduled airlines spent nearly three times as much, on average, on cabin crew training as the charter operators did. Cabin crew training costs for a range of UK airlines are given in the Table 2.1 below.

Table 2.1

Representative Costs of Cabin Crew Training for a range of UK Airlines (FY95/96)

| Scheduled Operator | | Charier Operator | |

| Number of Cabin Crew | Training cost per person | Number of Cabin Crew | Training cost per person |

| 575 | 625 | 911 | 198 |

| 853 | 1489 | 935 | 1310 |

| 1399 | 1616 | 1240 | 222 |

...