![]()

1 Introduction

Telling Failures—Early Encounters between East Asia and Europe

Ralf Hertel and Michael Keevak

Long before the period of classic, 19th-century Orientalism as defined by Edward Said, East Asian and European cultures encountered each other in manifold ways. Chinese, Japanese, and Korean documents on Jesuit visitors or European embassies, missionary reports, fictional depictions of East Asia included in works such as Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels or Voltaire’s L’Orphelin de la Chine, descriptions of, and by, East Asian pilgrims to Europe, as well as letters and accounts sent from Spanish, Portuguese, Dutch, and English trading posts are only some of the documents that present us with an insight into these many-faceted encounters. These documents remind us of the complex nature of early East-West relations: far from depicting situations which ‘put the Westerner in a whole series of possible relationships with the Orient without ever losing him the relative upper hand’—which Said thought characteristic for Western encounters with the Near and Middle East-, texts and images emanating from early interchanges between Europeans and Chinese, Japanese, and Koreans often question Western dominance.1 Driven by a hunger for expanding trade, the desire to spread the Christian faith, or the wish to establish diplomatic ties, Europeans frequently found themselves at the mercy of East Asian powers. It was not until the middle of the 19th century that Western powers gained some measure of control over their East Asian counterparts, notably in the Chinese Opium Wars and the forced opening of the Japanese market by American gunboats.

This study proposes to explore some of the complex relations between East Asia and the West in the period before the late 18th century. Its starting point is the realisation that models based on binary oppositions as advanced by Said, especially those implying Western domination, do not always apply to encounters between East Asia and the West. In fact, Western visitors repeatedly failed in many ways: on a linguistic level, they often failed to understand their interlocutors; on a cultural level, they failed to read the signs of cultural difference; on a political level, they failed to grasp their Asian counterparts’ intentions; and on the levels of trade and diplomacy, they frequently failed to realise their goals. Yet, if they failed, so did the East Asians who were repeatedly at a similar loss in their (first) encounters with Western cultures: What were the aims of those visitors from the West? How could one take advantage of, and at the same time control, their presence in Asia? What ambitions might Eastern powers harbour with regard to the West?

While inquiries into early encounters between East Asia and the West have traditionally focused on successful interactions, this study proposes to inquire into the many forms of failure, realising that recent postcolonial and transcultural approaches stressing the hybridising, productive effect of intercultural encounters often fall as short of early modern reality as Said’s concept of Orientalism. Decidedly countering a tendency to ignore unsuccessful encounters, this collection of essays starts from the assumption that failures can prove highly illuminating and provide valuable insights into both the specific shapes and limitations of East Asian and Western imaginations of the Other as well as of the nature of East-West interaction. Why, on what level, and how do encounters fail to fulfil expectations? What do these failures reveal about the expectations harboured by East Asians and Westerners vis-à-vis each other, and how might they make visible the implicit rules and cultural scripts governing such encounters? In other words, how might one understand these failures as telling failures? At the same time, this study crucially aims at studying both sides of the encounter, balancing Western views of East Asia with inquiries into Eastern perceptions of the West.

The essays collected here approach unsuccessful encounters from a variety of angles. Papers focus on both Asians and Europeans failing to deal with another culture, on failures taking place both in the East and in the West, as well as on failures in various periods ranging from first encounters in the early modern period to later interchanges immediately preceding full-scale imperialist interventions in the late 18th century. Early Encounters between East Asia and Europe explores the many different manifestations of failure in translations, in mercantile and military encounters, in religious discourse, and in diplomatic performances at court and elsewhere. At the same time, it analyses the ways in which these failures are represented, and transformed, in texts, images, and cultural performances, often compensating for failures by attempting to turn them into stories of success. What, in other words, are the narrative, visual, and performative strategies of coming to terms with failure?

While the final essay analyses failure from a theoretical point of view, other contributions opt for more empirical approaches. The question of failure not only extends and criticises a traditional Orientalist model, but it also has clear relevance to such fields as communication studies (failure in transmission), translation studies (failure in converting from one language to another), poststructuralist criticism (the ultimate failure of any text to communicate its intended meaning), religious studies (religious conversion), and the history of science (incommensurability and paradigm shifts).

* * *

The subtitle of this collection hints at three major aspects of failure the authors aim to address. ‘Telling Failures’ indicates, first of all, that we want to tell apart, to identify failures. Which failures are worth looking at? Second, we believe that many failures are telling failures, failures that reveal important insights in the cultures involved. What do failures tell us about those who fail, about the limits of their understanding? Finally, ‘Telling Failures’ suggests that we look at how failures are told, turned into narratives, verbalised, or represented in other media. What are the strategies in telling of failure?

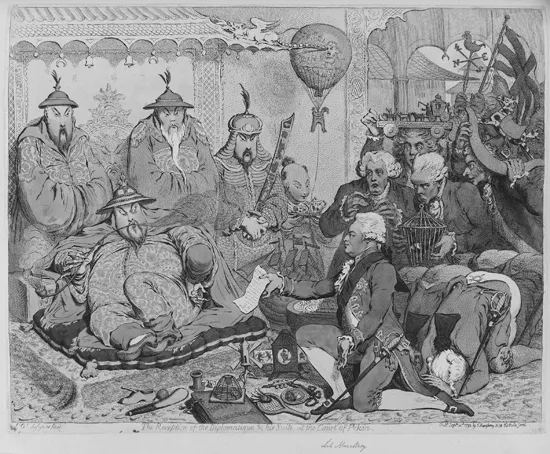

These implications are neatly illustrated by figure 1.1. This famous caricature by James Gillray shows Lord Macartney’s British Embassy to the Emperor of China in 1792. We see Macartney in the foreground with a letter from the English King George III requesting trade privileges, surrounded by his embassy carrying presents to the Emperor of China who apparently shows little enthusiasm. Gillray’s caricature is about telling failures in all the three senses mentioned. First of all, it tells of, or identifies, a scene of failure: Macartney’s embassy failed; the gifts—depicted here as a hotchpotch of useless toys—fell short of expectations, and the Emperor famously replied to King George that the Chinese do not ‘have the slightest need of your country’s manufactures’.2 Frustratingly for the British, the Emperor also refused to grant trade privileges. Discussed frequently, Macartney’s embassy hence is often seen as a pivotal moment in Anglo-Chinese affairs, marking a turn towards a more aggressive Western stance born out of frustrated hopes and eventually erupting in the Opium Wars of the 1840s and 1850s.

Second, the image depicts a failure that is a telling failure in so far as it sheds a revealing light on the hopes and expectations of the English—and the limits of their ability to conceive of Chinese mindsets. Macartney’s embassy brought along a variety of optical gifts in particular, visible in Gillray’s sketch, for instance, in the camera obscura placed next to Macartney’s right knee. These gifts reflected an Enlightenment stance typical for the period: the wish, and claim, to bring light and vision to the remotest parts of the world. However, the gifts utterly failed to impress the Chinese—who apparently were not sharing the English preoccupation with Enlightenment. In other words, in this print, the failure of the gifts foregrounds how the English projected their own cultural values and concepts onto the Chinese in a telling failure to grasp cultural difference.

In addition, the failure of the Macartney embassy also reveals how much English diplomacy was driven by mercantile interests. The diplomat Macartney here seems to be pushed forwards by his entourage, by those eager to profit from trade with China; his outstretched hand seems to be propelled forward by a ship and a roulette table—symbols of trade and capitalism. The man standing behind Macartney holds a string, which seems to pass through Macartney’s mouth, and ends in a hot air balloon, as if the merchants in Macartney’s entourage pulled the strings, and even controlled the diplomat’s words that, ultimately, were just hot air. Next to Macartney’s knee we see a magic lantern, its paper strip showing devil-like figures which the lantern’s projection transforms into a clown-like Punch figure. It is as though Gillray wanted to suggest that the Macartney embassy hoped to veil aggressive commercial expansion as harmless play, as play of mutual exchange.3

Finally, it is interesting to see how failure is told, or rather depicted here. In this case, it is worth noting who depicts it. As is well known, Gillray was not even there when the Emperor received the diplomat; what is more, Gillray did not travel to China at all. In fact, he produced this caricature even before Macartney had left Britain. Interestingly, in the person of William Alexander, there was a painter actually travelling with Macartney. Curiously enough, however, he was exclusively employed to paint the British gifts and British manufactures of porcelain in China. While Macartney visited the Great Wall, went to the Emperor’s court, and made world history, Alexander painted still lives of things British. What could demonstrate more clearly how little the English really wanted to ‘see’ China? For all their Imperial ambitions, the English could not really perceive the Chinese.

Gillray’s image, based in his imagination, reminds us of the fact that the representation of an encounter and its reality are often very different things; it reminds us of the fact that what we deal with are visions of East Asia, or, in turn, visions of the West—reflective imaginations that shed an illuminating light on those looking rather than on those being looked at. The following essays explore what these encounters might tell us, thus aiming to turn failures into telling failures.

* * *

Interdisciplinary in outlook, this study brings together the perspectives of sinology, Japanese and Korean studies, historical studies, literary studies, art history, religious studies, performance studies, and cultural studies. The subjects discussed are manifold and range from missionary accounts, travel reports, letters, and trade documents to fictional texts as well as material objects—such as tea, coffee, fruit, or chinaware—exchanged between East and West.

Focusing on failures in early modern relations between East Asia and the West, this collection of essays studies both sides of the cultural encounter and analyses East Asian and European documents and performances alike. While some papers inquire into Western perceptions of East Asia (e.g. Inke Gunia’s exploration of an early 15th-century Spanish embassy to the court of Tamerlane), others turn to East Asian views of European missionaries, embassies or traders (as, for instance, Marion Eggert, who studies Korean responses to early Jesuit missionaries, and Lars Laamann, who analyses Manchu reactions to attempts to convert them to Christianity). Others yet juxtapose Eastern and Western perceptions (e.g. Michael Keevak, who compares Chinese and Portuguese ideas of empire, and Rotem Kowner, who studies both Western and Japanese reactions to the Portuguese trade of Japanese slaves). A theoretically minded essay on the lessons of failure and the ethics of cross-cultural understanding (Q.S. Tong) rounds up the volume.

The first section of our volume is dedicated to the important field of trade relations, and the role failures play in it. Rotem Kowner’s essay, ‘A Failure Far from Heroic: Early European Encounters with Far Eastern Slavery’, probes into the intriguing but little known subject of Japanese slavery. When Portuguese traders arrived in Japan during the mid-16th century, they soon came across a vibrant local market of slavery and bondage, and with no apparent prohibitions, they soon began to export thousands of Japanese to other parts of Asia and even further afield. There was nothing unique about this Lusitanian trade. In many other parts of Asia, such as in the Indian subcontinent, Southeast Asia, and even in South China, the Portuguese and subsequently the Dutch were involved in precisely the same activity. On the Japanese side, however, the ways in which the local regime responded to this foreign trade not only made the phenomenon short-lived but also ensured that it did not have the negative impact it had on local communities in other parts of Asia and, needless to say, in Africa and the Americas. Kowner’s essay introduces the relatively unknown phenomenon of the European use of Japanese slaves in 17th-century Asia, examines the reasons why this trade ended in failure within decades, and discusses its effect on the preliminary Western conceptualisation of race with regard to the Japanese.

Ralf Hertel’s essay, ‘Faking It: The English Invention of East Asia in Early Modern England’, reads the story of early English encounters with the Far East as one of repeated failure. Latecomers on the stage of global trade, the English showed a strong desire to enter direct trade with China and Japan from the Elizabethan age onwards, yet were time and again frustrated in their expectations. Various expeditions tragically failed to locate the North-West passage, a letter from Queen Elizabeth to the Emperor of China apparently never reached its addressee, an attempt to sail up the Pearl River turned into disaster, and English factories in Japan and Taiwan were both short-lived and spectacularly unsuccessful. It is against this background that Hertel analyses intriguing literary hoaxes such as the invented ‘reply’ by the Emperor of China to Elizabeth (around 1600) or the Historical and Geographical Description of Formosa (1704) by the fake Formosan George Psalmanazar. If East Asians powers failed to respond to English advances, the writers of these hoaxes reacted to the English frustration by pretending to be spokespersons for East Asia with which the English so much wanted to come into contact. ‘Faking It’ takes a close look at the literary strategies employed in, and the ideological implications of, these pseudo-Asian texts, asking what they reveal about specifically English ambitions and anxieties—and their failure.

One of the most intriguing sources on East-West encounters in the early modern period is embassy reports, the focus of our second section. Inke Gunia’s contribution, ‘The Travel Report of the Castilian Embassy to the Court of Tamerlane at Samarkand (1403–1406): The Failed Response from Tamerlane to King Henry III of Castile and Léon’, focuses on one of the earliest travel reports in Spanish literature. In the Battle of Ankara of 1402, the Ottoman army was defeated by Tamerlane, and Bayezid I, sultan of the Ottoman Empire, was captured. The news spread to Spain, and King Henry III of Castile sent two embassies to East Asia. The second one started from Seville on 20 May 1403 and included Ruy González de Clavijo, whose journal gives intriguing details concerning geography, daily occurrences, architecture, and the customs of the people with which the embassy came into contact. Studying closely this travel report, Gunia foregrounds the tension between the actual failure of the embassy and Clavijo’s textual strategies of retelling this journey as a great achievement within the reign of King Henry III.

Opening up the temporal frame of our volume into the 19th century, Peter Kitson’s essay, The ‘Catastrophe’ of This New Chinese Mission’: The Amherst Embassy to China of 1816, focuses on the second British embassy to China, namely that of William Pitt, Lord Amherst, of 1816 and its relationship to the outbreak of hostilities between Britain and China in 1841 as recorded in John Francis Davis’ important but neglected Opium War publication Sketches of China (1841). While Macartney’s embassy of 1792–1794 has been widely researched, comparatively little has been written about its successor, which tends to be viewed largely as a farcical repetition of, or postscript to, its more famous predecessor. While contemporary responses to the Macartney embassy were mixed, with Macartney and his admirers regarding the embassy as a success, contemporary views of the Amherst embassy from both its participants and its critics viewed it as an unmitigated disaster. This paper focuses on the negotiations relating to the imperial ceremony of the sangui jiukou or koutou (anglicised as ‘kowtow’) and the exchange of presents. It argues that Amherst’s embassy is crucially important in challenging established British perceptions of China and the Qing court in the prelude to the Opium Wars of the 19th century.

Missionary accounts—the focus of our third section—provide similarly revealing sources for failure in early encounters between East Asia and the West. The spread of Christianity to Korea is usually told as a story of success. No other country in East Asia has been Christianised to the degree South Korea has; in the early 20th century, Protestant missionaries in Korea were jubilant about their successes in proselytising, and back in the 19th century, the large number of martyrs bespoke the firm standing of underground Catholicism. However, as Marion Eggert argues in her essay, ‘Failed Missions in Early Korean Encounters with “Western Learning”’, during the first two centuries of encounters with European scholarship (ca. 1600–1800), it would have been difficult to predict these later developments on account of the actual encounters between Jesuit missionaries and Korean emissaries to the Peking court. These were usually marked by the divergence of interests and a certain amount of mutual distrust. Among the factors that led ...