eBook - ePub

Gluck

About this book

This volume presents a collection of essays by leading Gluck scholars which highlight the best of recent and classic contributions to Gluck scholarship, many of which are now difficult to access. Tracing Gluck's life, career and legacy, the essays offer a variety of approaches to the major issues and controversies surrounding the composer and his works and range from the degree to which reform elements are apparent in his early operas to his contribution to changing perceptions of Hellenism. The introduction identifies the major topics investigated and highlights the innovatory nature of many of the approaches, particularly those which address perceptions of the composer in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. This volume, which focuses on one of the most fascinating and influential composers of his era, provides an indispensable resource for academics, scholars and libraries.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part I

Before Orfeo

[1]

Coming of Age in Bohemia: The Musical Apprenticeships of Benda and Gluck

DANIEL HEARTZ

Franz Benda, celebrated as a violinist and composer at the Prussian court, set down a memoir of his life and training when he was at the height of his fame in 1763. An anonymous friend of his gathered a different version of the same in what would today be called an oral history, written in 1766 and published the same year in Hiller's weekly newsletter concerning music.1 Benda was born in 1709, only five years before Gluck, and eight years before Stamitz, for both of whom we lack early biographical information. Some inferences can be drawn about them by analogy with Benda's biography. Other prominent Czech composers born in the first quarter of the century were Tuma (1704), Richter (1709), Seger (1716), and Benda's younger brother, Georg (1722).

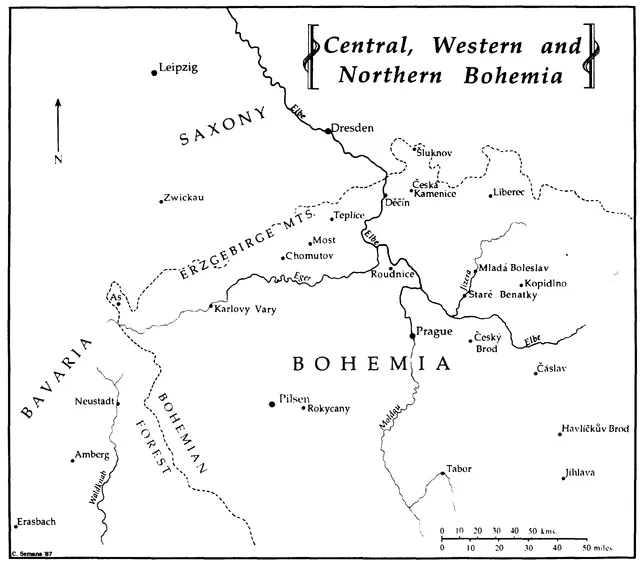

The Bendas are believed to have been of Jewish origins, the name coming from Ben David (Son of David), but the family had been Christian for several generations before the eighteenth century. Franz, baptized Frantisek on 22 November (the feastday of St. Cecilia), was born in the little town of Staré Benatky near Mladá Boleslav (Jung Buntzlau) on the Jizera river, a small tributary of the Elbe northeast of Prague (see map, Figure 1). His father was a linen weaver who also played the dulcimer, the oboe and the shawm in taverns, while his grandfather had been a steward on an aristocratic estate. His mother was Dorota Brixi, from a well-known musical family, the most illustrious member of which was František Brixi (1732—1771). He learned to read, write and sing at the town school, he says, "with the help of the skilled school-master, Alexius by name." At age nine he was taken to Prague by his father. They visited his cousin šimon Brixi (1693-1735), who was organist of the Týn Church. Brixi listened to him sing and read from sight, then promptly secured him a position as descantist in the St. Nicolai Church of the Benedictine cloister. His schooling was continued at the Jesuit Seminary, but he admits in all candor that he was much less interested in his studies than he was in visiting all the churches in Prague where good voices could be heard. We pass over certain details about overly indulgent friars, who lavished money on the young man, remarking only that Benda's ambitions to better his lot were early manifest.

FIGURE 1.

An opportunity arose to quit Prague and join the royal choirboys at Dresden, who were under the guidance of the Jesuits. The Prague Jesuits tried to stop him, but to no avail—he ran away. When he arrived in Dresden after a boat trip down the Elbe river he found his future colleagues playing ball: "As I could not speak German, I addressed them in Czech; they were nicely dressed and, since I wore nothing but an old vest, they looked down on me; but after I was heard singing, I was, three days later, just as well dressed." The anecdote says much about the age-old experience of the Bohemian musician, an alien in all the German-speaking lands surrounding his homeland, traditionally scorned (and not just for his poverty), yet making his way by sheer musical ability. It is just as poignant as Gustav Mahler's oft-quoted remark about his rootlessness: "I am thrice homeless, as a native of Bohemia in Austria, as an Austrian among Germans, and as a Jew throughout the world. Everywhere an intruder, never welcomed."2 Of Mahler's self-pitying tone there is not a hint in Benda's account. While Mahler tried to cover up his humble origins—his father was a distiller and seller of spirits—Benda relates his without shame, along with some remarkably intimate details of his relationships with other people. There is a refreshing lack of self-consciousness here, an earthy humanity that is typical of the eighteenth century and that scarcely survived the Victorian age.

After a year and a half in Dresden Benda had risen to become a favorite soloist of Kapellmeister Heinichen, who did not want to lose him. Experiencing a natural desire to see his parents, the young musician had no recourse but to run away again. Returned home, he resumed singing in the local church and played the part of a woman in a comedy with music written by his liege lords, the Counts of Clenau. They permitted him to return to his studies in Prague, where he was taken on as a contralto in the Jesuit Seminary in the Old Town. Once again he neglected his studies, but not his music. By this time (1723) he was fourteen.

The year 1723 was a momentous one for Prague, Emperor Charles VI arrived with an enormous retinue for his coronation as King of Bohemia. Musicians from near and far gathered for the celebrations, which were capped by Fux's opera Costanza e Fortezza (the title is the same as the royal motto chosen by Charles). It was given in the open air with a chorus of a hundred, of which Benda was one, and an orchestra of two hundred players. The Jesuits put on a Latin play for the Bohemian nobles in the library of the Collegium Clementinum. Entitled Melodramma de Sancto Wenceslao, it had music by the excellent Bohemian composer, Jan Dismas Zelenka (1679—1745), a disciple of Fux who was in the service of the Dresden court. Young Benda sang one of the parts. He dwells little upon this but much on the singing of the castrato Gaetano Orsini (1677—1750) from the Viennese court, who took the part of Porsenna in Fux's opera. Orsini's arias in Wenceslao were in Italian. They were quickly supplied with sacred contrafacta in Latin and sung in church by Benda, who claims he could remember most of them many years later when writing his autobiography.

The Italian vocal art, and in particular the art of the castrato, was one of the strongest musical impressions of Benda's youth, far from Italy though he was. It can have been no different with Gluck and Stamitz, or countless other Bohemian youths who aspired to musical greatness. Almost as strong an impression seems to have been made upon Benda by Italian instrumental music. At age fifteen his voice broke and he was forced to rely on other resources. He had played fiddle in taverns since he was eight, and had taken the viola part in instrumental concerts given by the Dresden choirboys. Now he began to practice the violin in earnest. He learned the concertos of Vivaldi by heart. As we know from a multiplicity of sources, Vivaldi's music was in great favor at both Dresden and Prague. Another great violinist, Tar-tini, had come in person to perform at the coronation ceremonies in Prague.

Benda was at an age when he was expected to earn his own living His father insisted that he keep playing as a Bierfiedler in the tavern, as well as learn to become a linen weaver. He soon aspired to marry the Burgomaster's daughter and applied for permission to do so to Count Clenau, to whom he was bonded as a "Leibeigene."3 The Count instead gave him money with which to go back to Prague and seek a good violin teacher. He found one in the person of Koničzek, who was in the service of Prince Lobkowitz, and to whom he paid a ducat a month for lessons. If Gluck and Benda ever met during their formative years, it would likely have been in the circle of the Lobkowitz musicians, for Gluck's family ties to this princely house were strong. Benda's violin lessons soon terminated because, as he says, Koničzek was unable to teach him more. Once again he returned home and resumed playing in the taverns.

The next episode Benda recounts takes on the character of an epiphany in his young life, all the more so because of his possible Jewish heritage:

In those days an old Jew, whose name was Lebel and who was born blind, used to play for dancing in another tavern. He was a man with quite excellent gifts for music. He himself composed the pieces and played exactly and very clearly, even the high notes (Hiller 1766,187, specifies up to high A) and he was able to make his instrument sound exceedingly sweet, although his violin was not particularly good. I often followed him to have the opportunity to think about the way he played and I must honestly admit that I received more stimulation from him than from my master to make my instruments sound as well as I could. Moreover, I am convinced that playing for the dance had done no harm to my artistry, particularly with regard to keeping time.

Given the exaltation of his later posts in royal service Benda writes with remarkable candor. He offers no apologies for having learned the soul of his art from someone so low in society, an old blind Jew, a Bierfiedler. His remarks, as innocent as they may seem, reveal sweeping vistas. Musical ideals were changing rapidly in the early eighteenth century. Sensuous tone, projected by a high treble voice or the violin with the utmost clarity and brilliance, combined with the rhythmic élan of the dance— these are qualities which, whether sounded by a soprano castrato, a Vivaldi or Tartini, or an uncommonly inspired popular fiddler, would eventually lead the new century to discover a musical personality of its own, distinct from that of the seventeenth century.

Count Clenau next sent Benda off to Vienna (1726) in order to serve in the household of his friend Count von Ostein, the intention being that Benda would perfect his skills and return to serve his hereditary lord as a valet. He remained until 1729 mainly in Vienna, where he met many musicians, one of the best violinists being old Timmer, who sang tenor at court (Hiller 1766,190). Most impressive, he says, was the playing of the celebrated Francischello, a cellist in imperial service (with whom he often played trios according to Hiller 1766,189). He formed a liaison of long duration with another young Bo...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Series Preface

- Introduction

- PART I BEFORE ORFEO

- PART II GLUCK IN VIENNA

- PART III GLUCK IN PARIS

- PART IV RECEPTION AND LEGACY

- Name Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Gluck by Patricia Howard in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.