- 200 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

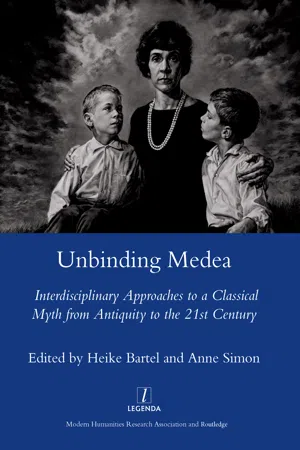

Unbinding Medea

About this book

Medea - simply to mention her name conjures up echoes and cross-connections from Antiquity to the present. The vengeful wife, the murderess of her own children, the frail, suicidal heroine, the archetypal Bad Mother, the smitten maiden, the barbarian, the sorceress, the abused victim, the case study for a pathology. For more than two thousand years, she has arrested the eye in paintings, reverberated in opera, called to us from the stage. She demands the most interdisciplinary of study, from ancient art to contemporary law and medicine; she is no more to be bound by any single field of study than by any single take on her character. The contributors to this wide-ranging volume are Brian Arkins, Angela J. Burns, Anthony Bushell, Richard Buxton, Peter A. Campbell, Margherita Carucci, Daniela Cavallaro, Robert Cowan, Hilary Emmett, Edith Hall, Laurence D. Hurst, Ekaterini Kepetzis, Ivar Kvistad, Catherine Leglu, Yixu Lue, Edward Phillips, Elizabeth Prettejohn, Paula Straile-Costa, John Thorburn, Isabelle Torrance, Terence Stephenson, and Amy Wygant.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

PART I

Departures

CHAPTER 1

Medea and the Mind of the Murderer

It seems surprising today that patriarchal Freudian psychologists originally adopted the figure of Medea in order to label the unconscious hatred of a mother for her maturing daughter, a phenomenon once labelled the ‘Medea Complex’.1 However, by 1948 it had been pointed out that the ancient Greek Medea had been the mother and murderer not of daughters but of sons.2 Actually, boys have in modern times always been far more vulnerable than girls to murder by their mothers.3 That Medea’s crime is today more frequently repeated than daughter-murder is perhaps simply coincidence rather than evidence for a psychological aetiology of the crime so fundamental as to be universally valid for all eras. However, it is most likely to be evidence of women reacting similarly in two societies which, although in other respects different, were marked by not dissimilar gender-based discrimination. Moreover, the greater modern instance of maternal son-murder needs to be seen in the wider criminological context, since women attack males of all ages far more often than they do other females in all types of murder and violent crime.4 As feminist criminologists have stressed, there are specific reasons why women kill and why it is usually their husbands, lovers and male children that they kill.5

Relative to some other domestic crimes, the sociological and psychoanalytical bibliography on maternal filicide is small, reflecting the horror it arouses. However, the data, such as it is, paints a consistent picture and one which is startlingly similar to the image of the child-killing mother painted by Euripides in his tragedy Medea. Study after study shows that in modern Western culture the average filicidal mother is in her mid-twenties (significantly, a decade younger than other female homicides),6 has been married only once, has two or three children and (unlike male filicidal parents) has custody of them,7 and has committed one prior offence.8 Educational deprivation is not as important a factor as might be expected; and although police and psychiatrists are far quicker to diagnose mental illness than they are in the case of male filicides,9 not a single study exists of evidence for mental impairment in filicidal mothers.10 Many studies of maternal filicide, including an important one in Illinois, reveal that almost all instances take place in the home, with the mother as the sole offender.11 A seminal North American study of parental filicide classified its primary motivations as altruism, psychosis, the fact that the child was unwanted, accident and (prominently) spousal revenge.12 In Canada, maternal filicides have been diagnosed as commonly motivated by revenge, with anger against the father being taken out on male progeny.13 The social isolation and strain on financial resources suffered by the mother are also crucial factors.14

Medea’s children are still young enough to be in her care rather than their father’s, that is, under eight years of age, which suggests that she is imagined as being under thirty years old. She has been married only once, has two children (in her sole care) and has committed a murder previously (that of her brother). The filicide takes place in the home, with the mother as the sole offender, and she is certainly suffering from social isolation and strain on her financial ability to look after the children. Her stated motives are overwhelmingly dominated by the desire for revenge on her husband Jason. She is well educated and her intellectual capacities seem to be unimpaired.

These several correspondences between the portrait of Medea and the all too frequent cases reported in our news media provide one reason why Medea is the most immediately accessible of all Greek tragedies. Another is that the figure of the child-harming woman, especially the mother who kills her own children, is undoubtedly the most reviled in our own cultural repertoire of villains. Although men as well as women kill their children in the immediate aftermath of a split from the co-parent, especially if the mother has a new sexual partner, they are not marked out for the same degree of cultural odium that their female counterparts endure. As the playwright Tony Harrison put it in Medea: A Sex-War Opera (1985), referring to the greater obloquy that Medea has attracted in comparison with her male counterpart in ancient myth, Heracles:

He killed his children. So where

is Hercules’s electric chair?

A children slayer? Or is Medea

The one child-murderer you fear?15

However, putting aside, if we can, the emotional circumstances — our reaction to the bloodcurdling violence and our identification with the little victims — it is important to realize that the strong apparent correspondences between the Euri-pidean Medea and the profiles of modern filicidal mothers are misleading. Our outraged abomination of the simple fact that Medea is responsible for her own sons’ death is a culturally specific reaction. Modern psychologists correctly insist that maternal filicide, far from being universally or absolutely defined as an atrocity, is perceived differently in different cultures; the marked variations in the way it is thought about are closely linked to economic, social and religious factors.16 Since Jason is effectively downgrading his own sons’ status relative to himself and their anticipated patrimony by taking a new wife and leaving them with their mother, it may be particularly relevant to the story of Medea’s murder of her children that an important factor in mothers’ valuation of and commitment to raising a child is, in many cultures, her perception of the father’s level of valuation and commitment to them.17 However, the figure of the Euripidean Medea is often discussed in absolute terms. Indeed, her filicide has frequently been held up as the ultimate example of the ultimate crime. The sadistic murder of her love rival has attracted infinitely less censure.

Since its origins, Greek tragedy has had a close and complicated relationship with criminal law. The ancient Greek word for an actor — hypokritës — also means an individual responding to interrogation in court. Similarly to legal trials, tragedies show crimes being committed and ask their audiences, like judges and juries, to assess the moral issues, attribute blame and authorize punishment.18 Some ancient Greek tragedies included trials (e.g. Aeschylus’s Eumenides); in the contemporary world, trials that are televised — like that of O. J. Simpson — raise questions about where reality ends and fiction and entertainment begin.19

One reason for the cultural longevity of Euripides’ Medea is certainly that it has so often been connected with discussions about criminal legislation as well as, more broadly, the treatment of women before the law. As early as the fourth century BC, just a few decades after Euripides’ masterpiece premiered in 431 BC, a famous tragedian named Carcinus gave Medea a highly legalistic speech in her own self-defence, in which she argued that it would have been irrational to kill the children while leaving Jason alive.20 In the eighteenth century, when Medea was regularly depicted as going mad, the play was adapted in ways that drastically diminished her criminal responsibility.21 In Victorian England, the prominent issue was the rival rights over children of divorced mothers and fathers, and the play was repeatedly staged in different adaptations around the time of the great 1857 Divorce Act.22 In the first decade of the twentieth century, productions across Europe began to address the question not only of women’s economic and social equality, but of women’s exclusion from the vote and politics.23 The crime of child-killing began to be seen as, in some cases, a woman’s response to a situation in which she was almost completely powerless, economically and politically.

Medea has more recently become a totemic figure. Later twentieth- and twenty-first-century Medeas have been reconfigured as victims of patriarchal oppression, stung into action only after years of suffering at the hands of men who have exploited their economic dependence in order to expose them to criminal abuse: Medea has even come to represent a symbol of resistance for women serving prison sentences for many more (and much more trivial) crimes than she ever herself committed. In California, a project initiated by Rhodessa Jones encouraging incarcerated women to use theatre to examine their pasts was entitled ‘The Medea Project’.24 However, the discussion here centres on another aspect of the law. It argues that one of the reasons Medea has proved so perennially fascinating is that it thinks about murder as a crime. In one sense, the identity of the victims does not matter, nor the sex of the killer: crucially, this is the first play in the Western theatrical tradition in which the audience watches, in great detail, someone make up his or her mind to kill and then carry out the decision. The play asks why people commit murder and shows how they wrestle with terrible emotions like anger and jealousy. The issue is made more complicated because the play does acknowledge that Medea has been involved in a killing before — that of her own brother years ago in the Black Sea. This, of course, raises the question of whether previous offences are relevant and can be used as evidence in a legal trial. However, the play, in particular, tackles head-on the issue of criminal responsibility by questioning the distinctions between ‘unprovoked’ murder and manslaughter under ‘provocation’ — what in the USA is called the distinction between ‘premeditated’ first-degree murder and ‘unpremeditated’ second-degree murder. Medea is the only surviving Greek tragedy in which a murder is committed in this ambiguous moral terrain. Clytemnestra’s murder of Agamemnon in Aeschylus’s Agamemnon has been planned for years and is therefore absolutely premeditated. Heracles in Euripides’ Heracles Furens and Agave in his Bacchae kill their children while demonstrably deluded and insane. The nearest parallels to Medea are actually offered by two other parents in Euripides. Creusa in Ion is persuaded to make an attempt on the life a youth she does not know is her son while she is sane but distraught. Agamemnon in Iphigenia in Aulis authorizes the sacrifice of his daughter when clinically sane but emotionally confused and under intense pressure from his brother and some sections within his community.

In the history of adaptations, from ancient Greece to the third millennium, the ambiguity inherent in the original Medea of Euripides has prompted numerous responses to Medea’s cr...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- List of Illustrations

- Notes on the Contributors

- Introduction: Medea, Meetings in Borderland

- PART I DEPARTURES

- PART II VISUAL PATHWAYS

- PART III THEATRICAL ENTRANCES

- PART IV APPROPRIATION AND EXILE

- PART V LAWS OF CONTAINMENT AND DISRUPTION

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Unbinding Medea by Heike Bartel in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & Languages. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.