CHAPTER 1

‘Aegri Somnia’: Towards an Aesthetics of the Grotesque

The road of excess leads to the palace of wisdom.

WILLIAM BLAKE, The Marriage of Heaven and Hell1

By the madness which interrupts it, a work of art opens a void, a moment of silence, a question without answer, provokes a breach without reconciliation where the world is forced to question itself.

MICHEL FOUCAULT, Madness and Civilization2

Both in antiquity and the High Renaissance, grotesque images, as David Summers has noted, were called ‘monsters’, because they were born of ‘unnatural combinations of natural things, or part of things’; due to the ‘ambivalent and contradictory’ couplings, according to Bakhtin, they were ‘contrary to the classic images of the finished, completed man, cleansed, as it were, of all the scoriae of birth and development’.3 Hence, for those who follow classical principles of art, grotesque hybrid monsters, as we shall see, mean nothing but ‘a catalogue of sins to be avoided’: the irrational, the improper, the disorderly, and so forth.4 On the other hand, for non- or anti-classical artists and critics, the grotesque marks a conscious break with classical tradition and is the quintessence of ingenium, novelty, and marvel.

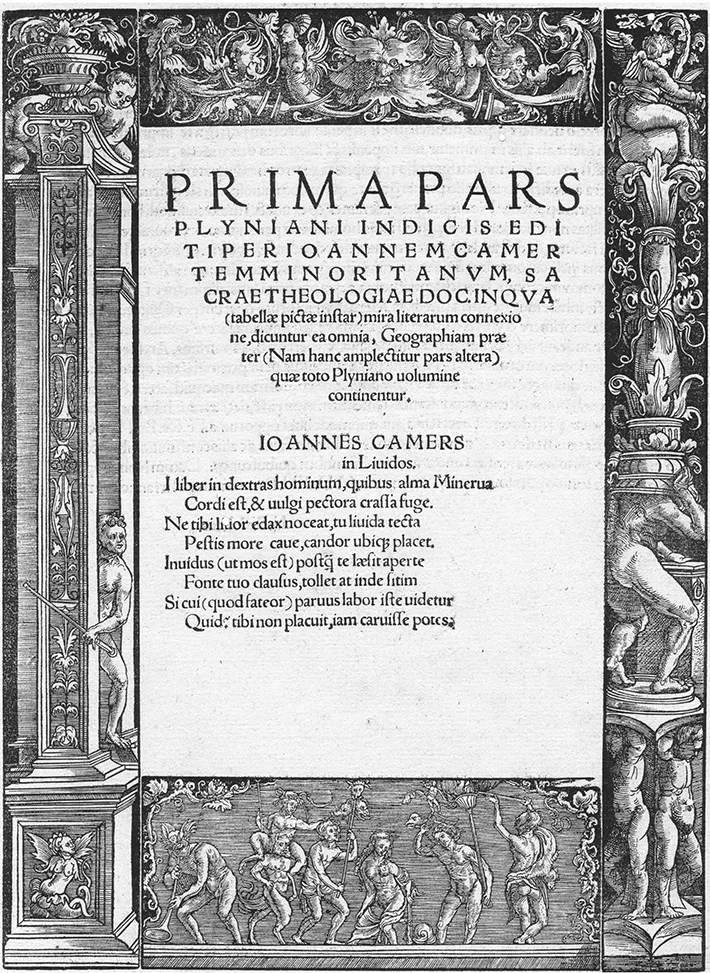

In light of the history of art (including literature), we see that the grotesque ‘thrives in an atmosphere of disorder and is inhibited in any period characterized by a pronounced sense of dignity, an emphasis on the harmony and order of life, an affinity for the typical and normal, and a prosaically realistic approach to the arts’.5 In other words, the grotesque blossoms in the aesthetic climates in which transgressing classical rationalism and order is greatly praised. Accordingly, whilst withering during the Age of Reason, the grotesque is ‘a hallmark of European Mannerism’ and continues to be popular in the Baroque because grotesque ornament is widely used during these two periods from architecture to book illustrations (Fig. 1.1); an epitome of Romantic creativity when Baudelaire, going further than Hugo, considers the grotesque, the incarnation of a permanent duality in the human condition, as the highest form of contemporary art; and almost a synonym of Surrealism, insofar as the grotesque embodies literally and figuratively the so-called surréalité.6

FIG. 1.1 Johannes Camers, C. Plynii Secundi Naturae historiarum libri XXXVII, 1518 © Trustees of the British Museum

Indeed, grotesque trans-formation is an excessive pursuit of incompleteness and contradiction: it transgresses the natural order of things and produces within itself a self-contradictory (or in-between) physical structure, one that, as we shall see, displeases classicists because of its ability to feed the feelings of (dis)pleasure and to obscure the borderline between life and death, beauty and deformity, the central and the peripheral. With this in mind, I propose to weave together the thread of furor poeticus, of the uncanny, and of the sublime, into an aesthetics of excess which defines the irrational nature — both in work and in response — of the (antique/ Mannerist) grotesque and which marks the critical role of the grotesque in the pursuit of the marvellous.

1. Origins of the Grotesque Monster

The fanciful hybrid images that adorned the chambers of the Domus Aurea, buried beneath the Baths of Titus, were discovered in the 1480s. Virtually unseen before then, they soon became an object of imitation in Italy and other parts of Europe, and the period that John Ruskin called ‘Grotesque Renaissance’ was thus born. By 1502, they were being called grottesche (grotesques) in Italy, according to where they had been found, in a grotta or ‘underground cave’.7 Markedly, the most intriguing and influential of High Renaissance/Mannerist grottesche was the decoration of the Vatican Loggia, completed in 1519 by Giovanni da Udine under the direction of Raphael. At the command of Pope Leo X, Raphael built the Loggia around 1515 and appointed Giovanni to decorate all the pillars there with, as Giorgio Vasari described, ‘most beautiful ornaments bordered by grotesques similar to the antique, and with very lovely and fantastic inventions, all full of the most varied and extravagant things that could possibly be imagined’.8

Vasari, who decorated the ceiling of the main corridor of the Uffizi Gallery with grottesche, was the cardinal figure in the codification of the grotesque in the sixteenth century. It was Vasari who highly valorized the fantastic or irrational nature of grottesche in his Le Vite (first published in 1550):

Grotesques [Le grottesche] are an irregular and highly ridiculous sort of painting, done by the ancients to adorn vacant space, where in certain places only things set up high were suitable. For this purpose they created all kinds of absurd monsters, formed by a freak of nature or by the whims and fancies of the workmen, who in this kind of picture are subject to no rule, but paint a heavy weight attached to the finest thread which could not possibly bear it, a horse with legs of leaves, a man with crane’s legs, and any number of bumble-bees and sparrows; so that the one who was able to dream up the strangest things was held to be the most able.9 (my italics)

To be sure, for Vasari’s Mannerist taste, the value of grottesche lies in the excess of classical norms of nature and reason.

Outside Italy, France was the first place where ornamental grotesques came into vogue. Before his death in 1527, Florimond Robertet, secretary to King Louis XII, already showed his enthusiasm for the invention of ornamental grotesques.10 Also, the major construction of grotesque ornamentation first began in 1530, when François I imported a team of Italian artists and craftsmen led by Rosso Fiorentino to decorate his new château at Fontainebleau in the most recent Italian ornamental style.11 The Fontainebleau grotesques were popular throughout the Continent during the second half of the sixteenth century. Meanwhile, the word ‘grotesque’, in the form crotesque, was introduced to France during the construction of Fontainebleau.12

Significantly, in an essay written before 1574, Montaigne describes that, motivated by grotesque paintings whose only charm lies in ‘variety and novelty’, he feels a desire to write his own essays in the same manner as ‘monstrosities and grotesques botched together from a variety of limbs having no defined shape, with an order sequence and proportion which are purely fortuitous’. He goes on to compare the formless style of his essays to the Horatian mermaid: ‘A fair woman terminating in the tail of a fish’.13 Making this comparison, Montaigne certainly had in mind Horace’s contempt for the invention of ‘a sick man’s dreams’ (aegri somnia): ‘a book whose different features are made up at random like a sick man’s dreams, with no unified form to have a head or a tail’.14 For Montaigne, however, aegri somnia are those which give rise to the charm of grotesques. Although Montaigne uses the term ‘grotesque’ figuratively to refer to heterogeneous composition, his favourable reference to grotesques not merely speaks to the Mannerist taste of his time, but also marks the first French literary use of ‘grotesques’.15 Moreover, his conception of the grotesque body as a product of fortuity or chance points ahead to the Surrealist game of le cadavre exquis; and the lack of a unified form of his essays, for Lyotard, exemplifies the postmodern (as opposed to modern) mode of fragmentation ‘without concern for the unity of the whole’.16

Montaigne’s use of monstrosities and grotesques together also brings out the fact that by the third quarter of the sixteenth century, the word ‘grotesque’ had the connotation of ‘monstrous’ in the French language. This was also the case in sixteenth-century Germany, where the first use of the word as the monstrous mixture of incongruent materials occurred in Johan Fischart’s introduction to Geschichtklitterung (History of Junk) of 1575.17 In addition, since the second half of the sixteenth century, the word ‘grotesque’ in Germany had been used to designate or describe exotic ornamental styles of non-Roman origin such as moresque, arabesque, Grubengrotteschische (which later became known as the school of diablerie), and so forth.18 In the sixteenth century, whilst Italy, France, Germany, and the Low Countries were absorbed in the extravagant grotesque style, there was no so-called ‘grotesque’ art in England — except that the word (in the French form) was first recorded in English in 1561.19 For the puritan climate of Tudor England was hardly congenial to the growth of grotesque ornamentations. Nonetheless, the late Elizabethan Age witnessed a rise of interest in Italian art and architecture, which was to develop during the next two centuries.20

Markedly, flourishing in seventeenth-century England, the word ‘grotesque’, as in sixteenth-century France and Germany, took on the connotation ‘monstrous’ or ‘chimerical’. In his Timber, or Discoveries (1640–41), for instance, Ben Jonson justifies his classical view of poetry and painting with recourse to Vitruvius’ and Horace’s rebuke against grotesque images; unlike Vasari and Montaigne, who valorized grottesche for their monstrosities, Jonson placed himself in the tradition of stigmatizing the grotesque as nothing but ‘chimaeras’ or ‘monsters against nature’.21 On the other hand, as the notion of the sublime was transplanted from France, started to strike root — with much effort, though — in the rational soil of Augustan England, and eventually bore the fruits of the Romantic expressive theory of art, grotesque monsters, as we shall see, found shelter in the sublime from the NeoClassical dogma of reason and decorum.

2. The Sleep of Reason22

Both Vitruvius and Horace ‘appeal in the Stoic manner to nature as a criterion for restraint’;23 their strongly disparaging views of grotesque art have become loci classici of much that is anti-grotesque. In his ten-volume interpretation of Roman architecture De Architectura (c. 27 bc), Vitruvius blames grotesque designs like those in the Domus Aurea for being ‘monsters rather than definite representations taken from definite things’.24 Rather than out of necessity, they were made to ‘flatter the habits of sense through the delight of the eyes and ears’,25 i.e. through the spell of the grotesque. Vitruvius then regards them as ‘improper taste’ of his time and concludes that only ‘[m]inds darkened by imperfect standards of taste’ cannot discern ‘whether any ...