Aristoxenians and Pythagoreans

Two major classical Greek sources on mathematical music theory have survived, both from roughly the late fourth century BC: the Harmonics of the peripatetic philosopher aristoxenus, and the Sectio canonis attributed, still somewhat controversially, to the geometer Euclid. Music theory texts from the first to the fourth centuries AD have survived in slightly greater numbers, and that of ptolemy – from the second century AD – is perhaps the most important for this book.1

There were two distinct traditions in the mathematical study of music in classical greece. For aristoxenus:

harmonics is a science whose data and explanatory principles are independent of those in any other domain of enquiry. its subject is music as we hear it, the perceptual data offered to the discerning musical ear. Its task is to exhibit the order that lies within the perceived phenomena; to analyse the systematic patterns into which it is organised; to show how the requirement that notes must fall into certain patterns of organisation, if they are to be grasped as melodic, explains why some possible sequences of pitches form a melody while others do not; and ultimately to display all the rules governing melodic form as flowing from a coordinated group of principles that describe a single, determinate essence, that of ‘the melodic’ or ‘the well-attuned’ itself.

The predecessors of aristoxenus in this approach to music were ‘“empiricists” of a cruder sort’. later writers who were – and are – called ‘aristoxenians’ tended to be academic systematisers, with less interest than aristoxenus himself in actual musical experience.2 These included the writers of what are now known as the ‘Aristoxenian handbooks’ of the second and third centuries AD: musical compilations and catechisms by cleonides, gaudentius, Bacchius and others.3

In contrast with the aristoxenian stood the ‘Pythagorean’ or, more generally, ‘mathematical’ approach to music theory. these pythagoreans:

were not typically interested in the study of music for its own sake …. The order found in music is a mathematical order; the principles of the coherence of a coordinated harmonic system are mathematical principles. and since these are principles that generate a perceptibly beautiful and satisfying system of organisation, perhaps it is these same mathematical relations, or some extension of them, that underlie the admirable order of the cosmos, and the order to which the human soul can aspire.4

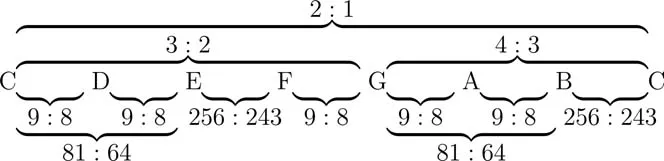

‘Pythagorean’ writers identified musical intervals with the ratios of lengths of strings, and discussed intervals by discussing those ratios. two otherwise identical strings whose lengths formed the ratio 2:1 would produce pitches one octave apart. The octave could therefore be identified with the ratio 2:1, and its specifically musical nature rapidly eclipsed by wholly mathematical or numerological theorising. this tradition is represented mainly by somewhat fragmentary evidence, but a mathematising approach shorn of numerological speculation was at work in the Euclidean Sectio canonis.

An essential difference between the aristoxenian and pythagorean approaches to music theory was the roles which they assigned to sense and to reason, and the relationship which they supposed to exist between them. the aristoxenian approach privileged the actual experience of hearing musical sounds, and tended to discount such results of pure reason as were not clearly descriptive of those experiences. The Pythagorean approach took the opposite line, privileging the results of reason applied to abstractions, and tending to disregard any objections the senses might raise to those results. the relationship between sense and reason in music would remain problematic, and would present increasingly complex difficulties, nearly a millennium and a half later.5

Our most important source from later in the Greek tradition discusses both the pythagorean and aristoxenian approaches to music theory: namely the Harmonics of ptolemy, written in the second century ad. ptolemy directed strong refutations at the Aristoxenians, but although, like the Pythagoreans, he identified musical intervals with the ratios of string lengths, he also took enormous care to provide experimental checks for his reasoned results about musical tuning.6

Classical Editions

The recovery of the ancient Greek musical sources began around the tenth century in Byzantium, and by the fifteenth century, manuscripts were being transmitted to Venice. This work of recovery of ancient music as a literary discipline rather than a repertoire may ultimately have contributed to the separation between theory and practice which we will meet in the seventeenth century.7 But our scholar in seventeenth-century England would not have had to consult rare and difficult manuscripts in order to have access to the Greek musical writings: indeed, not even the ability to read Greek would have been necessary. By the middle of the century, nearly all of the major texts had appeared in print, and many had been translated into latin.8

Henry Savile’s 1609 donation of manuscripts to the Bodleian Library included a copy of Ptolemy’s Harmonics, as well as another ancient Greek music treatise, that of Aristides Quintilianus. The Savilian professorships which he founded in 1619 were intended to promote all of the mathematical arts – including ‘harmonics’ or ‘canonics’, the mathematical study of music – and the Savilian professors were encouraged to prepare editions of relevant classical texts as well as lecturing. in 1627, Peter Turner, the Savilian professor of geometry, was employed by John Selden to ‘translate and collate’ Greek musical manuscripts including those of gaudentius and alypius, although that project did not result in a published edition. Later, the musician and scholar Edmund Chilmead worked on Oxford’s Greek musical manuscripts, and he began to prepare an edition of gaudentius which, in the event, was abandoned when it was superseded by the appearance of Marcus Meibom’s edition in amsterdam in 1652.9 Later still, in the 1680s and 1690s, another Savilian professor of geometry, John Wallis, published editions of the musical writings of Ptolemy, Porphyry and Bryennius.

The first Greek authors to be edited, around the beginning of the sixteenth century, were two who are now relatively obscure: Cleonides – an Aristoxenian – and Theon, both from the second century AD.10 Theon’s book on the mathematics required to read plato included a good deal of musical material and transmitted many fragments from other musical authors. after these, and an edition of the Euclidean Sectio canonis in 1557, the major editions introducing new texts were gogava’s of aristoxenus, ptolemy and aristotle in 1562, and johannes van Meurs’ of Nicomachus (from the first half of the second century AD) and Alypius (from the fourth or fifth century AD) in 1616. Fédéric Morel edited Bacchius (fourth century AD or later) in 1623. The sixteenth-century editions were strikingly concentrated in paris.

What may be called a second wave of publications began in 1644 with a new paris edition of theon. the remainder of the texts that had so far been published received new editions either from Marcus Meibom in 1652 or from john Wallis in 1682 and 1699; Meibom also provided the first editions of Gaudentius and aristides Quintilianus (both from the third–fourth century ad), and athanasius Kircher edited the surviving fragments of the writings of Archytas (fourth century Bc) in his Musurgia universalis of 1650.

Many of these editions were parallel Greek–Latin texts. Vernacular translations were much more unusual, and by 1700, only two texts had received them. these were cleonides’ Eisagoge harmonice (attributed at the time to Euclid), which was published in French in 1566, and capella’s late, encyclopaedic De nuptiis philologiae et mercurii, which contained a long section on music.

The overall result was that by 1600, most of the major texts, including those of Euclid, Aristoxenus and Ptolemy, had been published; by 1652, most of the Greek musical writings which are now known had been published, and the major texts existed in recent and fairly authoritative editions – with the sole exception of ptolemy’s Harmonics, a gap filled by Wallis in 1682.

We will see in the later chapters of this book how some of the particular issues present in the Greek sources were revisited in the seventeenth century. The roles of sense and reason and the implications of quantifying musical pitch using ratios would provide crucial questions for the reworking of mathematical music that took place in Restoration England.