eBook - ePub

Disability and Equality Law

- 576 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Disability and Equality Law

About this book

This interdisciplinary collection of essays addresses the theoretical, practical and legal dimensions of equality for persons with disabilities. The issues covered include the central problem of defining disability and impairment; the dilemma of same versus different treatment; the balance between autonomy and external influence and support; linkages to other anti-discrimination categories such as race and sex; the place of disability theory within identity politics; and issues of life, death, and our most intimate relationships. The articles reflect a wealth of international viewpoints and interdisciplinary areas which include philosophy, economics, memoirs, cultural studies, empirical studies and legal scholarship. The selection also includes classic texts which set out foundational ideas such as the social model of disability or the goal of integration, alongside essays that critique these conceptual mainstays. This volume brings into sharp focus a wide range of contentious and complex issues in the field of disability studies and is of interest to researchers and students from a wide range of fields.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part I

Definition and Models

[1]

Defining Impairment and Disability: issues at stake

Introduction

For the past fifteen years the social model of disability has been the foundation upon which disabled people have chosen to organise themselves collectively. This has resulted in unparalleled success in changing the discourses around disability, in promoting disability as a civil rights issue and in developing schemes to give disabled people autonomy and control in their own lives. Despite these successes, in recent years the social model has come under increasing scrutiny both from disabled people and from others working in the field of chronic illness.

What I want to explore in this chapter are some of the issues that are at stake in these emerging criticisms and suggest that there is still a great deal of mileage to be gained from the social model and that we weaken it at our peril. I will do this by briefly outlining the two alternative schemas which have emerged in the articulation of conflicting definitions of chronic illness, impairment and disability. I will then discuss six issues that, I suggest, go to the heart of the debate as far as external criticisms from medical sociologists are concerned. These ate: the issue of causality; the question of conceptual consistency; the role of language; the normalising tendencies contained in both schemas; the problem of experience; and finally, the politicisation of the definitional process.

Having identified the issues at stake externally, I will discuss a number of internal criticisms that have emerged from disabled people themselves around the place of impairment, the incorporation of other oppressions and the use and explanatory power of the social model of disability. While remaining sceptical about these criticisms, I will finally suggest that a start can be made towards resolving some of them by focusing on what disabled people would call impairment and medical sociologists would call chronic illness.

The Problem of Definitions

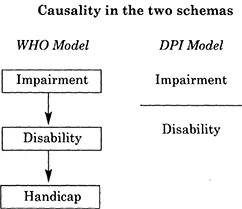

Since the 1960s there have been various attempts to provide and develop a conceptual schema to describe and explain the complex relationships between illness, impairment, disability and handicap. This has led to the adoption of the International Classification of Impairments, Disabilities and Handicaps (ICIDH) by the World Health Organisation (WHO) (Wood, 1980) which has been used as the basis for two national studies of disability in Britain (Harris, 1971; Martin, Meltzer and Elliot, 1988).

Not everyone has accepted the validity of this schema nor the assumptions underpinning it. Disabled people’s organisations themselves have been in the forefront of the rejection of the schema itself (Driedger, 1988), others have rejected the assumptions which underpin it (Oliver, 1990) and the adequacy of it as a basis for empirical work has also been questioned (Abberley, 1993). This is not the place to discuss these issues in detail; rather I intend to look at some of the dimensions of the debate that is currently taking place. In order to facilitate this, I reproduce the two alternative schemas below for those who are not familiar with either or both:

The WHO International Classification of Impairments, Disabilities and Handicaps:

‘IMPAIRMENT: In the context of health experience, an impairment is any loss or abnormality of psychological, physiological, or anatomical structure or function …

DISABILITY: In the context of health experience, a disability is any restriction or lack (resulting from an impairment) of ability to perform an activity in the manner or within the range considered normal for a human being …

HANDICAP: In the context of health experience, a handicap is a disadvantage for a given individual, resulting from an impairment or a disability, that limits or prevents the fulfilment of a role that is normal (depending on age, sex, social and cultural factors) for that individual’ (Wood, 1980, pp 27–29).

The Disabled People’s International (DPI) definition:

‘IMPAIRMENT: is the functional limitation within the individual caused by physical, mental or sensory impairment.

DISABILITY: is the loss or limitation of opportunities to take part in the normal life of the community on an equal level with others due to physical and social barriers’ (DPI, 1982).

The Issue of Causality

The search for causality has been a major feature of both the scientific and the social scientific enterprise. What is at stake for the disability schemas described above is how to explain negative social experiences and the inferior conditions under which disabled people live out their lives. For those committed to the WHO schema, what they call chronic illness is causally related to the disadvantages disabled people experience. For those committed to the DPI schema however, there is no such causal link; for them disability is wholly and exclusively social. Hence each side accuses the other of being incorrect in causal terms.

These schemas appear to be incompatible and have led one medical sociologist critically to suggest:

‘Sometimes, in seeking to reject the reductionism of the medical model and its institutional contexts, proponents of independent living have tended to discuss disablement as if it had nothing to do with the physical body’ (Williams, 1991, p. 521).

Ironically that is precisely what the DPI definition insists, disablement is nothing to do with the body. It is a consequence of the failure of social organisation to take account of the differing needs of disabled people and remove the barriers they encounter. The schema does not, however, deny the reality of impairment nor that it is closely related to the physical body. Under this schema impairment is, in fact, nothing less than a description of the physical body.

The appearance of incompatibility however, may be precisely that: appearance. It may well be that this debate is in reality, the result of terminological confusion; that real similarities exist between chronic illness and impairment and that there is much scope for collaboration between supporters of both schemas if this confusion can be sorted out.

The Question of Conceptual Consistency

This terminological confusion is not just a matter of agreeing to use the same words in the same way. It is also about understanding and appeared when a policy analyst attempted to relate her own experience to policy issues in the area of disability.

‘I found myself puzzled by arguments that held that disability had nothing to do with illness or that belief in a need for some form of personal adaptation to impairment was essentially a form of false consciousness. I knew that disabled people argue that they should not be treated as if they were ill; but could see that many people who had impairments as a result of ongoing illness were also disabled. My unease increased as I watched my parents coming to terms with my mother’s increasing impairments (and disability) related to arterial disease which left her tired and in almost continual pain. I could see that people can be disabled by their physical, economic and social environment but I could also see that people who became disabled (rather than being born with impairments) might have to renegotiate their sense of themselves both with themselves and with those closest to them’ (Parker, 1993, p. 2).

The DPI schema does not deny that some illnesses may have disabling consequences and many disabled people have illnesses at various points in their lives. Further, it may be entirely appropriate for doctors to treat illnesses of all kinds, though even here, the record of the medical profession is increasingly coming under critical scrutiny. Leaving this aside, however, doctors can have a role to play in the lives of disabled people: stabilising their initial condition, treating any illnesses which may arise and which may or may not be disability related.

The conceptual issue underpinning this dimension of the debate, therefore, is about determining which aspects of disabled people’s lives need medical or therapeutic interventions, which aspects require policy developments and which require political action. Failure to distinguish between these up to now has resulted in the medicalisation of disability and the colonisation of disabled peoples lives by a vast army of professionals when perhaps, political action (i.e. civil rights legislation) would be a more appropriate response.

The Role of Language

Despite recent attempts to denigrate those who believe in the importance of language in shaping reality, largely through criticisms of what has come to be called ‘political correctness’, few would argue that language is unimportant or disagree that attempts to eradicate terminology such as cripple, spastic, wobbler and mongol are anything other than a good thing.

This role of language, however, is more complex than simply the removal of offensive words. There is greater concern over the way language is used to shape meanings and even create realities. For example, the language used in much medical discourse including medical sociology is replete with words and meanings which many disabled people find offensive or feel that it distorts their experiences. In particular the term chronic illness is for many people an unnecessarily negative term, and discussions of suffering in many studies have the effect of casting disabled people in the role of victim.

The disabling effects of language is not something that is unique to disabled people. Other groups have faced similar struggles around language. Altman in his study of collective responses to AIDS points out:

‘… in particular the Denver Principles stressed the use of the term “PWA” as distinct from “victims” or “patients”, and the need for representation at all levels of AIDS policy-making “to share their own experiences and knowledge”’ (Altman, 1994, p. 59).

The struggles around language are not merely semantic. A major bone of contention is the continued use of the term ‘handicap’ by the WHO schema. This is an anathema to many disabled people because of its connections to ‘cap in hand’ and the degrading role that charity and charitable institutions play in our lives.

The Normalising Tendencies of Both Schemas

Underpinning both schemas is the concept of normality and the assumption that disabled people want to achieve this normality. In the WHO schema it is normal social roles and in the DPI schema it is the normal life of the community. The problem with both of these is that increasingly the disability movement throughout the world is rejecting approaches based upon the restoration of normality and insisting on approaches based upon the celebration of difference.

From rejections of the ‘cure’, through critiques of supposedly therapeutic interventions such as conductive education, cochlea implants and the like, and onto attempts to build a culture of disability based upon pride, the idea of normality is increasingly coming under attack. Ironically it is only the definition advanced by the Union of the Physically Impaired Against Segregation (UPIAS) that can accommodate the development of a politics of difference. While its definition of impairment is similar to that of DPI, its definition of disability is radically different:

‘DISABILITY: the disadvantage or restriction of activity caused by a contemporary social organisation which takes no or little account of people who have physical impairments and thus excludes them from the mainstream of social activities’ (UPIAS, 1976).

Again, this is not just a matter of semantics but a concerted attempt to reject the normalising society. That some organisations of disabled people have not fully succeeded cannot be explained only as a matter of dispute between different political positions within the disability movement but also as evidence of just how ingrained and deep-rooted the ideology of normality is within social consciousness more generally.

The Problem of Experience

Recently, a number of sociologists working in the general area of medical sociology and chronic illness have expressed concern over the growing importance of the ‘social oppression theory’ of disability, associated research methodologies, and their implications for doing research in the ‘chronic illness and disability fields’ (Bury, 1992).

Whilst these writers feel the need to ‘positively debate’ these developments, the basis of their concern is similar to that expressed by Hammersley with respect to some aspects of feminist research, i.e. the tendency to ‘privilege experience over sociological research methodology’ (Hammersley, 1992). In short, this privileging of experience is perceived as a threat; firstly, to ‘non-disabled’ researchers doing disability research; secondly, to the traditional role of the sociologist giving ‘voice to the voiceless’ – in this case ‘older’ disabled people whose interests are said to be poorly served by ‘social oppression theory’; and, thirdly, to the ‘independence’ of sociological activities within the ‘medical sociology world’.

As a social researcher, I have some sympathy for these concerns but the problem is that most social research has tended to privilege methodology above experience and, as a consequenc€, does not have a very good track record in faithfully documenting that experience; whether it be the black experience, the experience of women, the experience of disability and so on. Additionally, scientific social research has done little to improve the quality of life of disabled people. Finally, it is difficult to demonstrate that so called ‘independent research’ has had much effect on policy, legislation or social change (Oliver 1992).

The Politicisation of the Definitional Process

By now it should be clear that defining impairment or disability or illness or anything else for that matter is not simply a matter of language or science; it is also a matter of politics. Altman captures this in respect of the definitional battles surrounding AIDS:

‘How AIDS was conceptualised was an essential tool in a sometimes very bitter struggle; was it to be understood as a primarily bio-medical problem, in which case its control should be under that of the medical establishment, or was it rather, as most community-based groups argued, a social and political issue, which required a much greater variety of expertise?’ (Altman, 1994, p. 26).

This battle is related to two political processes; exclusion and inclusion as far as disabled people and disability definitions are concerned. The ways in which disabled people have been systematically excluded from the definitional process has recently been described in one incident which captures the nature of this exclusion more generally.

‘It is a hot summer day in London in the late 1980’s. Gathered together in one of the capital’s most venerable colleges is a large number of academics, researchers and representatives of research funding bodies. Their purpose? A symposium on researching disability comprising presentations on a variety of different methodological and other themes, given and chaired by a panel of experienced disability researchers.

Those convening the seminar are proud that it will shine a spotlight on a usually neglected area of social science research. But some in the audience (and one or two others who have chosen not to attend) hold a different view. What credibility can such a seminar muster, they ask, when none of those chairing or presenting papers are themselves disabled? What does it say about current understanding of disability research issues that such an event has been allowed to go ahead in this ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Series Preface

- Introduction

- PART I Definition and Models

- PART II Theories of Equality and Inclusion

- PART III Accommodation and Access

- PART IV Life and Death

- Name Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Disability and Equality Law by Michael Ashley Stein, Elizabeth F. Emens,ElizabethF. Emens, ElizabethF. Emens in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Geschichte & Arbeitsrecht. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.