![]()

PART 1

Ballet and Cantata

![]()

Chapter One

Ballet

Meyerbeer, the child of rich Jewish burghers from Berlin, received his first musical education as a seven-year-old from the music teacher to the Prussian Court, the pianist and composer Franz Lauska. Rapid progress on the piano directed the child prodigy along the path of a performing virtuoso. Lauska was no more able to bring out the child’s compositional gifts than the leader of the Berlin Music Academy, Carl Friedrich Zelter, and the director of the Berlin Court Opera, Bernhard Anselm Weber, who served as Meyerbeer’s teachers in the following years. Weber, nevertheless, as a devotee of the theatre, provided the young Meyer Beer (as his name originally was) with his first experiences in the area of dramatic composition. Under his direction the 19-year-old composed a one-act ballet pantomime Le Passage de la rivière, ou La Femme jalouse, planned and choreographed by the veteran ballet master Etienne Lauchery.

1.1 Der Fischer und das Milchmädchen oder Viel Lärm um einen Kuss [The Fisherman and the Milkmaid, or Much Ado about a Kiss]

Ländliche Divertissement [pastoral divertissement in one act]

Scenario: Etienne Lauchery

First performance: Hofoper, Berlin, 26 March 1810

In spite of his infantile precocity, the protection of his parents and extraordinary conditions of study, Meyerbeer was already 19 years old when his first stage work was performed. The name of the composer of this ländliche Divertissement was not mentioned. The French ballet master at the Court Opera, Etienne Lauchery, devised the scenario entitled Le Passage de la rivière ou La Femme jalouse (the crossing of the river, or the jealous woman) and choreographed the piece himself. The autograph score is headed Der Schiffer und das Milchmädchen / oder / Viel Lärm um einen Kuss / Ein pantomimishes Ballet in einem Aufzuge / Musik von Meier Beer. The hour-long work had four performances, and if the scenario has disappeared, it is still an attestation of Meyerbeer’s first encounter with the stage, and with French artists. The Fisherman was danced by Monsieur Telle, the Fisherman’s wife (the Hostess) by Madame Telle, the Milkmaid by Madame Lauchery, and the Sister of the Hostess by Mademoiselle Joyeuse, with Fräulein Holzbecker as the Niece and Herr Moser as the Forester.

It is a harmless tale of some countrywomen who should be doing their washing in a river, but are invited to dance by some young foresters. The Hostess and then the Chief Forester chide them all, but eventually end up dancing with them. The Fisherman comes with a catch that the Hostess wants to take to the village magistrate, because her husband is tired after work and wants to hang his nets to dry. A young peasant with milk jugs asks to be ferried across the river by boat. As reward, the Fisherman steals a kiss off her, which she resists. The Hostess comes back at this moment, berates the young girl, and throws her jugs in the river. The Milkmaid in her turn breaks the spinning wheel of the Hostess, annoying the jealous wife exceedingly. The Forester who happens to be passing by, listens to it all, laughs at the women, and calms the quarrelling.

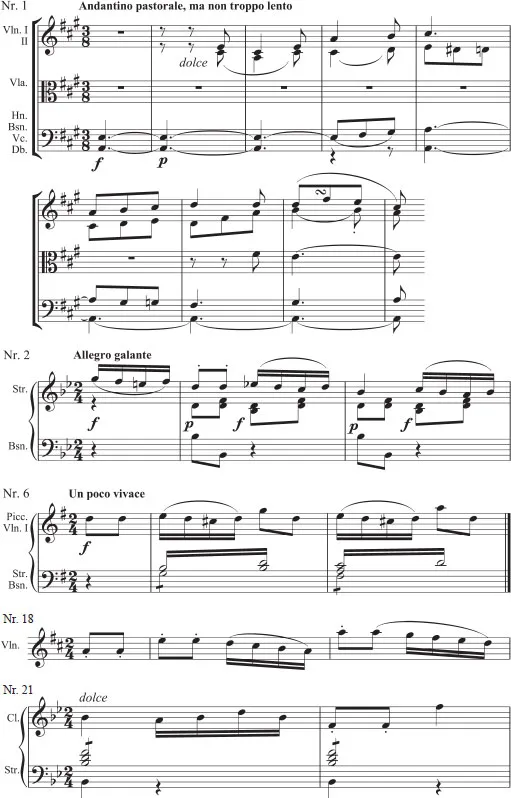

This friendly little story emerges from the time of the ancien régime, when Marie Antoinette had a neat little stylized village with artificial landscape built at the Petit Trianon. It is a harmless diversion provided with a prudish Prussian conclusion, for which Meyerbeer wrote music for 22 numbers. From a pastoral overture through an Allegro galante, an Air de Chasse, to the final Contredanse générale, the score contains everything that could be expected of a ballet-divertissement. Both small and large numbers show themselves heirs to the eighteenth century just passed, and are not distinguished melodically and harmonically from the minuets and contredanses of Mozart and Beethoven. The scoring for pairs of flutes, oboes, clarinets, horns, and the usual strings corresponds to contemporary standards. They are by no means all employed throughout, but rather differentiated woodwind writing brings an element of variety to the movements. Each number is self-contained, but there are recognizable relationships and similarities between individual parts, a turn of semiquavers that recurs in the melodic structure of several of the numbers, and works in its unconscious effect to create a sense of harmony and integration.

This is no youthful masterpiece, but a conscientiously constructed artefact, capable of sustaining a pleasing general impression.

Example 1.1 Der Fischer und das Milchmädchen: thematic patterns

![]()

Chapter Two

Cantata (Oratorio/Dramatic Monologue/Duodrama)

In the same year that he composed his ballet Der Fischer und das Milchmädchen (1810), new and exciting artistic prospects were opened for the young composer when the famous music theorist and composer Georg Joseph Vogler invited him to Darmstadt as his pupil. Here his fellow students were Carl Maria von Weber and Johann Gänsbacher. Meyerbeer’s compositional and aesthetic development was to be authoritatively and enduringly influenced by the learned and cosmopolitan Abbé. The artistic consequences of two years of intensive study were to find expression in the oratorio Gott und die Natur (1811) and the opera Jephthas Gelübde (1812).

2.1 Gott und die Natur [God and Nature]

Lyrische Rhapsodie [lyrical rhapsody—sacred cantata]

Text: Aloys Wilhelm Schreiber

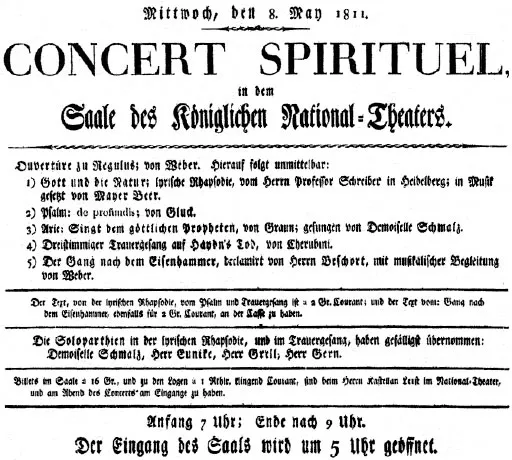

First performed: Singakademie, Berlin, 8 May 1811

In February 1811 Meyerbeer received the text of an oratorio Gott und die Natur from the poet and professor of aesthetics Aloys Wilhelm Schreiber, an acquaintance of the Abbé Vogler from Heidelberg. The young composer applied himself so fervently to the task, that as he wrote to Gänsbacher on 27 February ‘he could not unfortunately even think about letter-writing’. This work, overwhelmingly lyrical in character, contains much of significance in the composer’s later dramatic development, and represents a milestone in his career. It was composed at Darmstadt at Vogler’s home, and consists of a loosely connected series of solos and choruses setting forth the creation of the world, its end in the Last Judgement, and culminating in praise of God. The orchestra comprised the usual strings, double woodwinds (with piccolo, a third bassoon and double-bassoon), four horns, three trumpets, three trombones, three timpani and harp. Schreiber had observed in his Lehrbuch der Asthetik (# 356): ‘Opera music has its great difficulties because music already by its very nature cannot be dramatic, whereas the play, when it does not want to unite with music, of necessity must take on a lyrical character.’ Whether Meyerbeer knew of this opinion, hardly encouraging for his future career, remains doubtful. In his oratorio he did not in the first place need ‘dramatic music’, but rather united all the effects of counterpoint and tone colour then at his disposal, and wrote a work in which one notes the models of Handel, Hasse and Haydn without hearing them.

Illustration 2.1 Gott und die Natur: the playbill of 8 May 1811 (from the collection of the late Heinz Becker)

Example 2.1a Gott und die Natur: the opening chorus and fugue (creation)

Unlike Haydn’s late masterpiece Die Schöpfung (1798), with its classical dramaturgy moving from nothing to light, Gott und die Natur is a song of praise for God’s creation and saving power. The opening chorus and fugue, in their downward rushing impetuosity, exalt the primordial and cosmic divine intervention (No. 1) (ex. 2.1a).

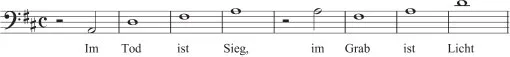

The existence of living things (No. 6, the Chorus of Flowers) or the birth of the elements are celebrated (No. 8): Air (soprano), Fire (alto), Earth (tenor) and Water (bass) each have a particular theme linked by a short four-part bonding motif, so that in all eight themata are unfolded, set over against each other, intensified, and then contrapuntally fused, a feat Weber greatly admired. The solo contributions show an operatic sensibility. The Song of Air is notable for the tracery of the flute part that plays around the vocal line. The Song of Fire, with the colour of the alto voice, is dominated by a chorale-like theme ‘Meine Kraft ist still und rein’ (my power is silent and pure), sustained by solemn chords of the trumpets, horns and bassoons, with the trumpets penetrating the leading horns, and the wide intervals of the supporting bassoons lending the chords a hollow sound. After a credal confirmation of the divine metaphysics by the chorus (No. 10) that ‘Er war, er ist, and er wird seyn’ (God was and is and will be), there is debate in duet form (No. 11) between a doubter (Zweifler) and an atheist (Gottesleugner). The young composer attains an extraordinary intensity of expression in the last numbers. The Day of Judgement (No. 12) is powerfully portrayed. Strings enter mysteriously with ‘Hörst du die Posaune klingen?’ (Do you hear the trombone sound?), and over grave clarinets, horns and trumpets the voices of the chorus float whisperingly. A tremendous crescendo roll on the timpani sees the fortissimo entry of the whole orchestra, with the chorus proclaiming ‘Sieh des Grabes Riegel springen’ (See, the grave’s bolt sprung). Demisemiquaver strings rush above the words ‘dunkel heulenden Meer’ (dark howling sea), and at the words ‘Jehova spricht’ against contrasting chords, followed by a fading sound effect depicting the horror of impending chaos, the chorus intones the words ‘Dumpfe Donner hallen, alle Sterne fallen’ (Dull thunder rolls, all stars fall) while the orchestra, in downrushing, chromatically diminished seventh chords, sinks into soundless darkness. A hollow roll on the timpani punctuates the silence, whereupon from on high the soprano announces the general resurrection: ‘Es lebt, was je geboren war’ (All lives that was ever born). The other soloists join in with a chorus hushed in awe, underpinned by subsiding strings like rays of hope. Edgar Istel (1926, 83) goes so far as to see this as a ‘tone-picture reminding one of Michelangelo’s famous frescos’. The closing male-voice chorus announces a confident and faithful expectation of redemption, a broadly conceived fugue on the ascending theme ‘Im Tod ist der Sieg, im Grab ist Licht, das Wort des Herrn, es trüget nicht’ (In death is victory, in the grave is light, the Word of the Lord does not deceive). This is elaborated into a double fugue with technical mastery, and reveals a talent for formal artistic development (ex. 2.1b).

Example 2.1b Gott und die Natur: the closing fugue (redemption)

In the tersely elegant themes, stately tempi and choral fugues in lengthened notes, Meyerbeer carries over into his dramatic music the magnified style of his earlier Klopstock songs. The treatment of the chorus and the attraction of musical pictorialism show the influence of Handel where there is a similar intermingling of theatrical and oratorio styles. It was very important for the young composer to learn how to dispose big movements formally, a task he would be called to confront constantly in the challenges that lay ahead.

There have been two performances of this work in recent times: a live broadcast from the Teatro Communale in Bologna on 21 February 1996 (with Anja Kampe, Monica Minarelli, James McLean, and Andrea Serra Giaretta, with the Chorus and Orchestra of the Teatro Communale di Bologna, conducted by Rüdiger Bohn), and a concert in the Basilica of Kevelaer on 21 November 1999 (with Christine Alexander, Monica Mascus, Thomas Ströckens, Marcus Lemke, with Wolfgang Seifen on the organ, and the Basilikachor Kevelaer and orchestra conducted by Boris Böhmann).

The first work completed by Meyerbeer after his move to Italy in 1816 was a small scenic cantata for soprano, male chorus, ballet and orchestra, with instrumental obbligato, composed for the benefit of some friends.

2.2 Gli amori di Teolinda [The Loves of Theolinda]

Cantata di scena per soprano, clarinetto, coro e orchestra [stage (secular) cantata for soprano, clarinet, chorus and orchestra]

Text: Gaetano Rossi

First performance: Verona, 18 March 1816

Meyerbeer’s stay in Munich, and the production there of his first opera Jephthas Gelübde, are intimately bound up with the careers of two great artists: the clarinettist Heinrich Baermann who played the first clarinet in the Munich Hofkapelle and was considered one of Europe’s finest instrumentalists, and his lifelong companion, the soprano Helene Harlas Baermann,. Carl Maria von Weber composed his First Clarinet Concerto for Baermann, who used a method of soft-blowing and was a...