- 644 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Aquinas and Modern Law

About this book

This volume collects some of the best recent writings on St. Thomas's philosophy of law and includes a critical examination of Aquinas's theory of the relation between law and morality, his natural law theory, as well as the modern reformulation of his approach to natural rights. The volume shows how Aquinas understood the importance of positive law and demonstrates the modern relevance of his writings by including Thomistic critiques of modern jurisprudence and examples of applications of Thomistic jurisprudence to specific modern legal problems such as federalism, environmental policy, abortion and euthanasia. The volume also features an introduction which places Aquinas's writings in the context of modern jurisprudence as well as an extensive bibliography. The volume is suited to the needs of jurisprudence scholars, teachers and students and is an essential resource for all law libraries.

Trusted by 375,005 students

Access to over 1 million titles for a fair monthly price.

Study more efficiently using our study tools.

Information

PART I

Introduction to Aquinas

1

On Reading the Summa

An Introduction to Saint Thomas Aquinas

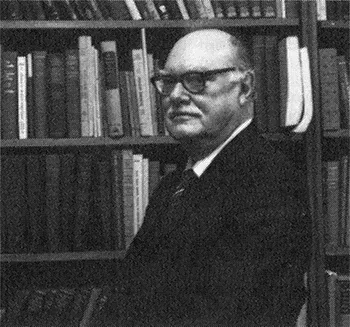

Born and raised in Ann Arbor, Michigan, Otto Bird attended the university there, graduating in 1935 with honors in English. He added a master’s degree in comparative literature the following year. He took his doctorate in philosophy and literature at the University of Toronto in 1939.

From 1947 to 1950 he served as associate editor of the Syntopicon for Great Books of the Western World, working with Mortimer Adler. In the latter year he joined the faculty at the University of Notre Dame, where he was founder and director of the general program of liberal studies until 1963. He was executive editor of The Great Ideas Today from 1964 to 1970, when he was appointed university professor of arts and letters at Notre Dame, from which he retired in 1977. In 1986 he was distinguished visiting professor of the humanities at the University of Dallas.

He has written four books, The Canzoné d’Amore of Guido Cavalcanti with the Commentary of Dino del Garbo (1942), Syllogistic Logic and Its Extensions (1964), The Idea of Justice (1967), and Cultures in Conflict (1976), besides articles on the history and theory of the liberal arts. In addition, he was a major contributor to the Propaedia, or Outline of Knowledge, of the current (fifteenth) edition of the Encyclopaedia Britannica.

Mr. Bird now spends much of the year in Shoals, Indiana, where he has built a house and grows grapes for making wine. He continues to be active in editorial projects of Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc., and remains consulting editor of The Great Ideas Today. He has contributed to many of our volumes. His essay on Euclid appeared last year.

Someone opening and paging through the Summa Theologica for the first time is almost certain to be puzzled, if not disconcerted and even repelled. Page after page contains the same unvarying subdivisions, sections entitled “Articles,” each of which begins with an interrogative sentence, asking whether such and such is so. The one-volume Latin edition contains 2,777 pages plus an additional 69 pages of indices, listing all 3,112 of these Articles. Reading the text, we find that the same procedure is followed in every one of these Articles, unvarying, stereotyped, monotonous. The language too is plain, unadorned, impersonal—almost entirely lacking any appeal to the imagination. If the reader comes to the text expecting to find high thoughts expressed in high and moving language, he is bound to be disappointed. We may well ask why anyone would ever want to adopt such a style and method of writing.

To this, the first and simplest answer is that Thomas was following and improving upon the methods used in the schools in which he spent his entire life. At the age of five he was placed in the monastic school of the Benedictines at Monte Cassino, and during the rest of his life he studied and taught at various universities and houses of study in Naples, Paris, Cologne, and the cities in Italy where the papal court was located. About the only time he was not in the schoolroom was when he was in church or walking from one school to another; the trip from Naples to Paris, for example, took two months, and he seems to have made it at least four times. Furthermore, practically all of his many writings not only grew out of the practice of the schools but were also addressed to their members, which is to say that they were intended for a specialized and highly trained audience. In this respect his work differs greatly from that of Saint Augustine, for example, who, when he was not addressing his own parishioners and through them all Christians, was writing for a generally cultivated audience.

Thomas refers to the methods used in the theological schools of his day in declaring that he intended to improve upon them. In the general prologue to the Summa he notes that beginners in theology have been hampered in their study by two of the methods then in use. One is that of expounding and explaining a text (librorum expositio), in which one has to follow the plan of the book being read. The other is that of disputing and discussing questions raised during the reading of the text (occasio disputandi). Both methods, he claims, weary and confuse the student in that they fail to follow the order and organization proper to the subject matter and discipline of theology (ordo disciplinae).

The “beginners” (incipientes) he is talking about here and addressing were students who had graduated from the faculty of arts in the university and entered the faculty of theology. In other words, in our terms, they were graduate students, and those at the University of Paris in the thirteenth century had already studied much logic and a lot of Aristotle. By the time that Thomas became such a beginner in 1252 the course in theology had become established and fixed in a form that was to remain the same down to the Renaissance and the Council of Trent. It consisted of a four-year course of studies in which during the first two the beginner was a “Biblical Bachelor” (Baccalaureus Biblicus) engaged in a cursory reading of the entire Bible, both Old and New Testaments. During the final two years he was a “Sententiary Bachelor” (Baccalaureus Sententiarius), because he was engaged in teaching the Four Books of Sentences compiled by Peter Lombard in Paris in about 1150. The teaching of this text was not restricted, as it was on the Bible, to exposition and commentary (lectio, expositio) but could wander away from it to investigate and discuss questions suggested by the reading of the text, the disputatio. Once the four-year program was satisfactorily completed, the bachelor was declared a Magister in Sacra Pagina and licensed to teach in any faculty of theology.

Thomas spent his four years as a bachelor in theology at the University of Paris, and we still possess the Commentary on the Sentences that he then wrote. This work can throw considerable light upon the great Summa that he began in 1267 and was still writing when he died in 1274. That is so not only because of the influence it exercised with regard to both matter and method but also because the completion of the Summa that is now contained in the Supplement to the Third Part consists of materials excerpted and rearranged from the Commentary on the Sentences. Comparing the Supplement with the Commentary, we can see how the former was put together by conforming to the method adopted for the Summa, and how it makes an improvement in clarity. For that purpose we will look at the initial questions dealing with the resurrection, beginning with Question 75 of the Supplement (GBWW, Vol. 20, p. 935a).

The corresponding place in the Sentences occurs in the fourth book. There, in accordance with the plan of the book, the relevant scriptural passages on the resurrection are cited first, after which selected passages on the subject are quoted from the fathers of the church. These judgments constitute the “sentences” from which the work derives its name. Those of Saint Augustine are much the most frequent, some ten times as many as those from any other authority, according to one count.

Thomas’s Commentary, like those of other commentators, is much more complex. The Lombard text is divided up into sections called Distinctiones, which in turn are divided into Quaestiones. Each of these consists of Articuli, which in turn are subdivided into Quaestiunculae, which form the smallest part. Thus, in his Commentary on the 43rd Distinction of Book IV, after quoting the text from the Sentences on the resurrection and noting how it can be divided, Thomas has one Question with five Articles, each of which contains three or four Quaestiunculae. These consist of arguments, usually from some church fathers, often disagreeing with one another. After all of these have been stated, Thomas then gives his own solution or decision about each of them. Thus he proceeds from one Article to another. Merely from this description of it one can see why the Summa's prologue complains of “the multiplication of . . . questions, articles, and arguments.”

After the death of Thomas, his first editor could bring about a considerable simplification merely by excerpting and rearranging Thomas’s words in his commentary according to the plan he had established in the Summa. Thus the 5 Articles under Question I of Distinction 43 are made into 5 Questions of the Supplement (QQ. 75–78 and 87), and the Quaestiunculae become their respective Articles. The work was obviously much of a “scissors-and-paste” job, the signs of the original being indicated by frequent references to words of the Master, i.e., Peter Lombard, or merely to “the text” (PART III SUPPL, Q 76, A 2, ANS; GBWW, Vol. 20, p. 941c).* It should also be remembered that they are words taken from his earliest work and, consequently, do not reflect his mature thought such as we have it in the rest of the Summa.

The method and plan of teaching the Sentences is obviously complex and cumbersome. Why then was it adopted and continued in use for more than three centuries as the basic way of teaching theology? (One effect of this use was that Thomas himself until the mid-sixteenth century was known more for his comment on Peter Lombard than for his revolutionary Summa.) Here again, the simplest answer is to be found in the practice of the schools and the preferred mode of the disputation. The books we have of that practice are but written records of what, as actually carried on, was an oral and not a written tradition. To understand and come to appreciate the intent of these books, including the Summa itself, it helps greatly to know the what and the how of their disputations.

The disputation

There are extant many records of disputations held in the medieval universities, including those that Thomas himself held. From these as well as from the laws and rules by which the universities were governed, especially those of the University of Paris, much can be learned about the actual conduct of these disputations. From such sources we can gain some insight into the actual life that lies behind the conception and writing of the Summa.

The disputation constituted the most solemn public academic exercise held in the university. On the day one was to be held, all other activity in the university was canceled so that all might be free to attend. There were two kinds of disputations, the ordinary and the extraordinary. The latter were called Quodlibetales, in that they were held only at special times on which occasions a master would announce his intention to entertain any question (i.e., theological) that anyone wanted to offer and engage in argument about it. The ordinary one that was a regular part of the academic program was the Disputed Question (Quaestio Disputata). In this case a master would announce in advance a subject, i.e., the quaestio, which he proposed to discuss and, along with it, the points of inquiry under which he would consider it.

The dispute lasted for two days. The first day provided the public occasion that was open to the entire university, indeed to the public at large, and could last from six to eight hours. At this time the master presided only, and his students, one or more of them, were responsible for presenting the arguments and meeting any questions or opposed arguments; the master would intervene only if the discussion got off the track, as it were, or if he wanted to come to the aid of his student. Reporters took down in writing the arguments advanced and then, apparently on separate sheets, the answers given to them.

The second day of the dispute was private, inasmuch as the master met only with his own students, went over the arguments of the previous day, developed his own position on the question, and offered answers to the arguments contrary to his own position. This session in turn became public since the master was required to turn over to the university authorities within ten days his written version of the two-day disputation. It is such reports as these that exist today as Quaestiones Disputatae or Quodlibetales, as the case may be.

These reports, even though they have been revised and edited by the master, take us as close as we are likely to get to the actuality of a medieval disputation. We have many of Thomas’s own, since he was willing and able to engage in both kinds of disputation. The Quodlibetales were especially demanding, and some masters never offered to hold one. Thomas seems to have disputed once or twice a month while at Paris. He held ten disputations, for example, on the power of God, and the text of the report still reveals something of how it was conducted. In the Article of one Question (Q. 4, A. 2) we find thirty-four arguments presented on one side of the question and ten on the opposite side; often two opposing arguments appear side by side without being separated into distinct groups. This indicates that the respondent frequently gave his answering argument as soon as an opposing argument was advanced, as is shown by the text noting that “the answerer said” (sed dicit respondens), which is then followed by a counterargument. With so many arguments being advanced both pro and con, it is not surprising that a dispute could last for an entire day and require a second day for the master to state his own position.

It bears noting that the two days of the d...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Philosophers and Law

- Acknowledgements

- Series Preface

- Introduction

- Selected Bibliography1

- PART I Introduction to Aquinas

- PART II The Problems of Natural Law

- PART III Law and Morality

- PART IV Natural Law and Natural Rights

- PART V Dimensions of Positive Law

- PART VI One Thomistic Critique of many Modem Jurispmdences

- PART VII A Thomistic Approach to Selected Legal Problems

- Conclusion: The Modern Return to Aquinas

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Aquinas and Modern Law by James Bernard Murphy,JamesBernard Murphy, Richard O. Brooks in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.