- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

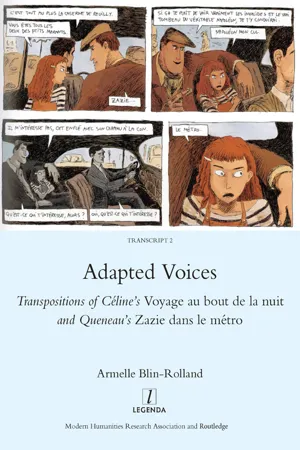

Adapted Voices

About this book

Voyage au bout de la nuit (1932), by Louis-Ferdinand Celine (1894-1961), and Zazie dans le metro (1959), by Raymond Queneau (1903-1976), were two revolutionary novels in their transposition of spoken language into written language. Since their publication they have been adapted into a broad range of media, including illustrated novel, bande dessinee, film, stage performance and recorded reading. What happens to their striking literary voices as they are transposed into media that combine text and image, sound and image, or consist of sound alone? In this study, Armelle Blin-Rolland examines adaptations sparked by these two seminal novels to understand what 'voice' means in each medium, and its importance in the process of adaptation.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

PART I

❖

Literary Voices

CHAPTER 1

❖

(Mis)appropriating the Other’s Voice in Voyage au bout de la nuit

‘Ça a débuté comme ça. Moi, j’avais jamais rien dit. Rien’ [Here’s how it started. I’d never said a word. Not one word] (CV, p. 15): in the famous opening of Voyage, a voice breaks the silence to which it will return at the end of its ‘immense’ monologue, with ‘tout, qu’on n’en parle plus’ [everything, let us talk no more of it] (CV, p. 632).1 As the introduction to this volume has shown, voice is constructed through a process of assimilation and adaptation, and this is fundamental to Voyage. In Latin’s words, throughout the novel and its ‘parole-écriture’ [parole-writing] the reader hears ‘le timbre profond d’une voix’ [the distinctive timbre of a voice], that of protagonist-turned-narrator Ferdinand Bardamu.2 With the word ‘timbre’, Latin refers to the way in which the text creates the mirage of a spoken voice, and to the distinguishing feature of this oralized voice. It is the transposition of features of spoken and popular language that gives the text its “‘ton” dominant’ [dominant ‘tone’], as Nelly Wolf states.3 But the narrative voice is also characterized by its heterogeneity, in the way that it is constructed out of, and through the collision with, other voices. This has been shown by Godard, who analyzes the Célinian narrative voice through Bakhtinian concepts, and in particular heteroglossia and dialogism.4 Godard identifies the variety of French (‘les français’) used by Céline, which have their own lexicon and, sometimes, syntax, and include popular language, army language, medical language, and literary and philosophical language.5 Significantly, Godard shows how Célinian texts use these languages dialogically, as voices in the Bakhtinian sense, that it to say as the incarnation of an interpretative position within heteroglossia.6 The orchestration of voices into an artistic whole is what makes Célinian texts polyphonic, and even verging on cacophonic in their linguistic heterogeneity.7

In Voyage, the narrator Bardamu also uses the voices of his characters dialogically, as he collides with and denounces other discourses. David Décarie gives the example of Bardamu’s parodic stylization of the voice of Dr Bestombes, the head doctor of the hospital for wounded soldiers to which he is committed, as a way to challenge the discourse of patriotism. Décarie points out that the text takes to an extreme the violence that is inherent to Bakhtinian polyphony, by confronting and, in places, ridiculing the discourse it is transposing.8 Linguistic heterogeneity and multi-voicedness are brought together in one over-arching voice subverting written language. Constructed out of, and in relation to, other voices, the Célinian narrative voice is, in Godard’s words, ‘unique et une plus encore que multiple, [ce] qui fait la force de l’œuvre’ [unique and one, more so than it is multiple, which is the strength of the work].9

This chapter will use the model of ventriloquism to further explore how the dialogue, and tension, between voices is key to Voyage at the narrative level, in the relationship between the instances that are perceived as figural voices by the reader, namely the narrator and the characters. Bardamu is a first-person narrator animated by revenge, and his monologue is a retroactive reading, in which he retraces his evolution from listener to teller. As the voice through which all others must now be heard, he exploits his ventriloquial power in various ways to challenge other voices, and to construct and impose his own. The model of ventriloquism enables us to explore the orchestration of the characters’ voices, as well as the vacillation between two possible selves, in the exchange between Bardamu and the character of Robinson. Constructing his voice out of and against the other, animated by a need to tell, Bardamu also engages in a complex relationship with the reader who will hear him in his or her auralized reading of his monologue. This chapter will first briefly situate how the construction of a striking voice in Voyage is inscribed in its historico-literary context, and, in order to avoid repetition later in this volume, provide a short synopsis of the novel.

‘Le premier livre d’importance où pour la première fois le style oral marche à fond de train (et avec un peu de goncourtise)’*

The above quotation about Voyage, written by Queneau, posits Céline as a pioneer of orality. The idea that Céline was ‘the first’ (a point emphasized by Queneau through repetition) is echoed by Godard in his 1985 Poétique de Céline. However, as Meizoz points out in his study of what he terms ‘the age of the speaking novel’, it is important to reconsider the image of Céline as a ‘précurseur solitaire’ [solitary precursor] and to understand his works as historically-situated, singular yet inscribed in contemporary linguistic and literary debates.11 During the interwar years the gap between written and spoken language is at the centre of debates between grammarians and linguists, the former (such as André Thérive) retaining a prescriptive and purist approach, and the latter (such as Charles Bally) adopting a descriptive approach to theorize spoken French and its ‘mistakes’. This is echoed in the literary field, with writers as diverse as Charles-Ferdinand Ramuz, Blaise Cendrars, Jean Giono, and Henry Poulaille transposing features of spoken language into the novel and, significantly, oralizing the narrative voice.12 This subversion of literary language is itself inscribed in a long-term reflection on the relationship between spoken and written language, starting in the nineteenth century, which Gilles Philippe retraces in La Langue littéraire.13 Significantly, there are echoes between the controversial critical reception of Céline’s Voyage and that of Zola’s L’Assommoir in 1877, in which Zola attempted to reproduce a working-class voice by using non-standard French not only in direct speech, but also in the narrative voice through free indirect speech.14

Céline’s ‘mauvais français’ [bad French] in Wolf’s terms, and his construction of a striking oralized narrative voice are coherent in this context of linguistic and literary exploration of the gap between written and spoken language.15 Bellosta has shown in particular Céline’s relationship with proletarian literature, and Voyage was in fact considered a proletarian novel by critics such as Georges Altman, who compared Céline to Henri Barbusse and Poulaille.16 Yet Céline is, in Bellosta’s words, ‘un prolétarien anticommuniste’ [an anti-Communist proletarian], and Voyage is of course a novel that is ideologically deeply ambiguous.17 The singularity of Céline’s trajectory in this context of ‘the age of the speaking novel’ would become obvious with the publication of Mort à crédit. Indeed, as Philippe points out, Céline’s aim, ‘tel qu’il apparaît plus clairement dans Mort à crédit, n’est pas de faire de la littérature avec le français parlé “tel qu’il est, tel qu’il existe”’ [as it becomes more apparent in Mort à crédit, is not to create literature from spoken French ‘as it really is, as it exists’], as Queneau believed in his ‘Ecrit en 1937’, but ‘de faire entendre une “voix” dans le texte’ [to get the reader to hear a ‘voice’ in the text].18 The ways in which Céline plays with voice(s), and how this is already articulated in the relationship between the figural voices in Voyage, will be the focus of this chapter.

Voyage defied classification due not only to its political ambiguity, but also to the ways in which it combines different genres and models. Owing to the importance of the First World War in the text, it can be linked to the genre of the war novel (such as Barbusse’s Le Feu, published in 1916); it is also in some ways an adventure or travel novel, contributing to the construction of a mythology of colonial Africa and of New York in literature, and echoing modern anxieties about industrialism and capitalism.19 The novel tells the story of Ferdinand Bardamu, a medical student who enrols in the army to fight in the First World War, and is profoundly shocked by its absurdity and violence. During a reconnaissance mission he meets Léon Robinson, a soldier who is trying to desert, and who will turn up at each step of Bardamu’s journey. Bardamu is wounded and, upon his return to Paris, becomes romantically involved with Lola, an American nurse volunteering in France, the first of a number of failed affairs. Traumatized by the war, Bardamu suffers from hallucinations and is committed to a hospital for wounded soldiers. He then embarks for Africa, where he becomes the manager of an isolated colonial rubber trading post, taking this position over from Robinson. After falling sick and setting fire to the post, Bardamu is sold into slavery as an oarsman on a Spanish ship going to New York. Alone and poor in New York, his experience of the United States contrasting so vividly with the hopes he had nourished of the ‘New World’, Bardamu goes to Detroit, where he works in a mind-numbing job on the assembly line for Ford. Bardamu eventually returns to France, where he stays until the end of the novel and becomes a doctor. Bardamu sets up his medical practice in La Garenne-Rancy, a poor and grim Parisian suburb, in which he is further confronted by misery, people’s repulsive tendencies, and meanness. He finds himself involved in a case of attempted murder, as Robinson is accidentally blinded after having been hired to get rid of an old woman, la mère Henrouille, by her son and daughter-in-law. Robinson and la mère Henrouille are sent to Toulouse to cover up the story, where Robinson becomes romantically involved with a young woman called Madelon. He eventually tires of her, and seeks shelter in the psychiatric hospital where Bardamu now works. Madelon finds him, and a day out at the funfair meant to reconcile them ends tragically as Madelon shoots Robinson. Bardamu watches his friend die, and the novel ends with Bardamu alone on a canal bank. It is fifteen or twenty years later when Bardamu breaks the silence again, but this time as a narrator to tell his story.

From Protagonist to Narrator, from Listener to Teller

In order to understand how Bardamu uses the power he acquires as narrator, it is important to analyze his evolution from protagonist to narrator, listener to teller, and his relationship with other voices. As it has been much noted, there is a stark contrast between Bardamu as a naive protagonist, and Bardamu as an older, disillusioned narrator. Solomon points out that this difference in knowledge and experience creates throughout the text a ‘continuing, ironic interplay’.20 Godard sees this contrast as an aspect of the polyphony of the text, in the superimposition of two voices within one individual.21 These two voices are indeed strikingly different, yet as a character, Bardamu shows abilities that prefigure his evolution into a narrator. This is seen in his gift for story-telling, and it is in fact when he is telling fake stories that his voice is avidly listened to. His American lover Lola will not accept the truth he tells her about war, but enjoys his made-up stories about the races at Longchamp (CV, pp. 76–77). During his visit to Robinson in Toulouse, he delights the guests on a luxury houseboat with his ‘bobards impromptus’ [impromptu cock-and-bull] (CV, p. 510), and Dr Baryton, the director of the psychiatric hospital, with his aggrandized life adventures, ‘pérégrinations […], arrangées évidemment, rendues littéraires ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Dedication

- Acknowledgements

- Translations Used

- Introduction

- Part I: Literary Voices

- Part II: Text/Image Voices

- Part III: Soundtrack Voices

- Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Adapted Voices by Armelle Blin-Rolland in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & Languages. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.