![]()

Chapter 1

Fire Insurance and British Economic Growth, 1700–1850

That, Sir, is the good of counting. It brings everything to a certainty, which before floated in the mind indefinitely.

Samuel Johnson.1

This chapter examines the growth of fire insurance in eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century Britain, places the industry in its economic context and explores some of the likely determinants of its growth. Necessarily it is concerned with national aggregates rather than with the local or regional variations which are the subject of subsequent chapters. Two obvious ways to measure growth are to examine the number of policies issued or the number of properties insured. Unfortunately these data were rarely recorded by the insurance offices of the period or have failed to survive. However, we are able to construct, for the first time, annual time series for sums insured and premium income for the period 1720–1850. Without taking Johnson’s apothegm too seriously, this data should interest everyone concerned with the relationship between British economic development and the growth of financial services. One of the deficiencies of the various national income accounts constructed for this period has been the service sector. Deane and Cole noted the ‘absence of information’, and Crafts, when attempting to calculate the real output growth of the British economy, commented that services constituted ‘the most problematic part of the measurement’.2 The usual solution has been to assume that this sector grew at the same rate as population. This assumption must now be questioned in the light of the estimates presented below. They provide the most accurate and detailed quantitative account yet of the development of any major service industry during the Industrial Revolution.

The contours of the industry: numbers, employment and capital

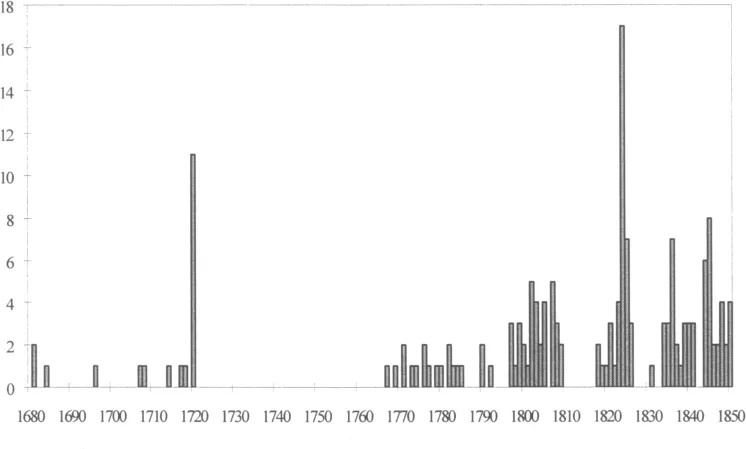

Counting British insurance offices is not an exact science. This is true even for the period after 1782 when annual returns of stamp duty on fire insurance were first made. A published breakdown of the duty paid by individual offices in England and Wales is first available from 1821, and for offices in Ireland and Scotland from 1824.3 Furthermore, collection of the duty was never exact, and some insurers, mostly small, short-lived offices, failed to appear in the returns. Nevertheless, using these returns, supplemented by a range of other sources, we have identified 169 fire offices established in Britain and Ireland between 1681 and 1850. These are shown in figure 1.1.4

Figure 1.1 New fire offices established in Britain and Ireland, 1680–1850

Source: see text.

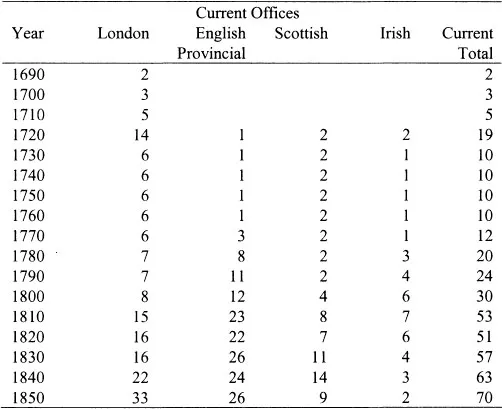

The graph indicates that company formation was highly cyclical and concentrated over time. Eighty-four per cent of all offices were established during five distinct periods – 1717–20, 1797–1809, 1818–26, 1834–41, 1844–50. Seventy- seven offices were founded in just 11 years (1720, 1802–3, 1807–8, 1824–5, 1835–6, 1844–5). Table 1.1 shows end-of-decade totals for Britain and Ireland. Throughout this period the population of fire offices remained small compared with other sectors in which corporate or partnership forms of business organisation predominated. In the early 1780s there were over 100 banks in existence and just 18 fire insurance companies. By 1800 there were about 30 country banks in England and Wales for every country fire office. In 1814 there were over 160 river and canal navigations, compared to the 70 fire offices established by that date. One hundred and forty gas companies existed in 1826, but fewer than 60 fire offices. The railway mania of the 1840s produced 25 new railway companies for every new fire office established during that decade.5 With the largest manufacturing industries the differential was greater still. Around 1800 there were over 1300 common brewers in England and Wales, and in 1838 there were over 4200 factory- based textile firms in Britain. Such numbers highlight how rare a sight was an insurance company on the British economic landscape.6

General patterns in the geography of company formation are also evident from table 1.1. The promotions of 1720, associated with the speculative boom which led to the South Sea Bubble crisis of that year, were almost exclusively London-based. By contrast, the steady growth in the number of offices after 1760 took place exclusively outside London. By 1780 provincial offices were in the majority, and this remained the case until the 1840s. The numerical gap between London offices and the rest was widest after the boom of the early 1820s. Just nine of the 37 offices established between 1819 and 1826 were located in London. By 1830 only about one in four British fire insurance companies were metropolitan. Because of corporate takeovers and new company foundations, this trend was subsequently reversed so that by 1850 the ratio was nearly one in two. Most provincial offices, however, were relatively small. The proportion of UK insurances sold by non-London offices was just 13 per cent in 1810, rising to 33 per cent by 1850.

Although the number of fire insurance offices was modest, how important were they in terms of employment creation and capital accumulation? The financial sector has always been regarded as having a poor capacity to generate jobs by comparison with primary or secondary industries. This may explain why historians have largely ignored the labour question when discussing financial services. At first glance, the orthodox view seems to hold for fire insurance. The number of salaried and waged employees of insurance offices remained tiny in relation to their ‘output’ and ‘income’, measured by sums insured and premiums received. The largest London offices had permanent staffs of no more than 15 for most of the eighteenth century, 20 to 30 during the early nineteenth century, and still fewer than 50 by midcentury. Using the data in table 1.1 and the records of 16 companies, it is estimated that there were only about 80 permanent full-time staff employed by all British fire offices c.1750, about 250 in 1800 and nearly 800 by 1850.

Table 1.1 Fire insurance offices in Britain and Ireland, 1690–1850

Notes: For the purposes of counting current totals, where the fate of an office is unknown, it is presumed to have ceased underwriting in the decade following its establishment. The Suffolk & General (established 1802) had two divisions, ‘east’ and ‘west’, which were listed separately in the duty returns before 1837. This is counted as one office in the above table.

Sources: Duty returns 1822–50; Trebilcock, Phoenix Assurance, pp.451, 495, tab.8.4;Insurance Yearbook 1981/2; Walford, Insurance Cyclopaedihich; Walford, ‘Fires and Fire Insurance Considered’; Raynes, History of British Insurance; Ryan, ‘History of the Norwich Union’; Jenkins, ‘Practice of Insurance against Fire’, pp. 19–20; GL Ms 16170/2, Atlas, DM, 27 May 1813.

Beyond the small numbers of clerical staff many others gleaned an income from insurance offices. Housekeepers, doorkeepers, cleaners, watchmen, porters, messengers and collectors could be found either among the permanent establishment or the casual staff. Solicitors, printers and stationers, metal and leather workers, tailors, buttonmakers, painters, carpenters, carvers, plumbers, bricklayers, glaziers and smiths provided the fire offices with a range of services and equipment by fee or retainer. Teams of building workers were contracted to repair and rebuild insured property which had been damaged or destroyed. Fire ‘preventers’, caps and hooks for firefighters were supplied by numerous small artisans, mostly in London, as well as fire engines and leather hose by the better known firms such as Newsham & Ragg. Firemen’s uniforms, hats and boots were manufactured, leather buckets cut, sewn, and lacquered by the dozen, firemarks cast and gilded by the hundred. Many suppliers of smaller items were women, including six of the twelve individuals paid through the Sun’s petty accounts between the 1730s and 1750s for firemarks, buckets, preventers, buttons and rolling press work. Ann Humphreys earned over £22 in 1739 for supplying and mending buckets. Mary Taylor succeeded her late husband as painter to the Sun in 1740, and earned over £60 that year for painting the office and gilding 1500 firemarks. Over the period 1739–59 Ann Bagley earned an annual average of £15 for casting thousands of lead firemarks for the Sun.7

It is impossible to reconstruct the numbers earning a crust in these ways. However, some idea of the size of two groups of part-time employees, firemen and agents, can be obtained from scattered references in company records.8 During the eighteenth century most London offices maintained brigades of between 24 and 50 firemen and auxiliaries. Some provincial offices also had fire brigades. The Kent Fire Office employed at least 63 firemen in several Kentish towns in 1809. Estimates suggest about 250 employed by British insurers in 1750, over 500 in 1800, and about 1000 in the 1810s and 1820s, before numbers fell rapidly with the advent of the London Fire Engine Establishment in 1833 and the municipal fire brigades which followed. The population of insurance agents, on the other hand, rose rapidly from over 100 in 1750, to over 800 in 1800 and 13000 by 1850. The numbers are crude, but aggregating the three major groups of permanent and parttime staff, we arrive at the following totals; nearly 500 in 1750, 1600 in 1800, 4000 in 1810, 5300 in 1820, and 14100 by 1850.9 According to these estimates, total insurance employment remained a tiny fraction of the occupied population of Great Britain – about 0.02 per cent in 1750, and 0.15 per cent a century later.10 Yet the absolute numbers employed may surprise those who have dismissed labour creation by the financial sector during the Industrial Revolution. Moreover, the above estimates suggest that employment in fire insurance grew ten times faster than the growth of the occupied population.

Using these figures, and the series for real sums insured discussed below, we can make a crude estimate of labour productivity.11 The results suggest that per caput real output fell by 60 per cent between 1750 and 1810, from £0.17m to £0.07m. This was an effect of the expansion of agency networks by the London stock companies, of increasing levels of competition, and of the ever wider trawl for business, which frequent...