This is a test

- 198 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Changing English Countryside, 1400-1700

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The period covered by this book, first published in 1987, was an important one for the rural landscape in England. The author describes and analyses the evolution of the countryside during the years which witnessed the gradual disappearance of the medieval landscape and the introduction of new farming methods and industrial techniques, thus laying the foundation for the radical changes that were to transform the English countryside in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The main features of the countryside are dealt with fully and examples are given of their remains which can still be identified in the landscape today.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Changing English Countryside, 1400-1700 by Leonard Cantor in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

CHAPTER 1

The English countryside in 1400

England in 1400 was overwhelmingly a rural country and, by today’s standards, very thinly peopled, its total population being probably about 2¼ millions. Over 90 per cent of the people obtained their livelihood from farming and lived in villages, hamlets and isolated farmsteads in the country, though, as we shall see, both the size of the population and the extent of the cultivated land were smaller than they had been fifty years earlier. Industry employed very few people full-time, possibly little more than 1 per cent of the population, although it provided part-time work for many more, as a supplement to peasant agriculture. Scattered up and down the countryside were a large number of market towns, but they were very small and probably fewer than twenty provincial centres had as many as 3000 people. Even London, by far the largest town, had a population of only about 40,000 and, like every other town in the kingdom, had the countryside immediately at its doorstep. Nevertheless, the towns played a key part in the rural economy, providing markets for agricultural produce, supplying traded and manufactured goods to the rural population, and acting as social, cultural and religious centres.

However, for the vast majority of the population, who lived in the countryside, their overwhelming preoccupation was to obtain from the land they farmed the basic needs of food and shelter for themselves and their families. Virtually everything they ate, drank, wore and used for fuel they obtained from the crops which they grew, the animals which they reared and from the raw materials of the countryside outside their homes, which they built for themselves. Peasant life in the late Middle Ages was a hard one. Medieval food was often distasteful, with heavily salted meat, for those who could afford it, throughout the winter, and rancid butter in the hot weather of summer. Farming life was extremely demanding and more often than not very hard: the peasant rose with the sun and went to bed when it got dark. He had few mechanical aids to assist him and for many, especially those farming on poor soils, crops were thin and food barely adequate. Bad harvests caused real hardship and a succession of two or three could result in disaster and starvation.

The typical English peasant in 1400 was understandably of smaller stature than the Englishman of today and was a Catholic in a country which was part of Catholic Europe and in which religion played a dominant role. In terms of landholding, however, there was no such thing as a typical peasant in late medieval England. Although they all worked on the land, some peasants were free men and some were of servile status, though more and more of the latter obtained their freedom as time went on. By 1400 some had acquired substantial farms and might even employ labourers to work on them, while others occupied only enough land to sustain themselves and their families. They all had in common, however, the fact that they held their land by right of the lord of the manor, from whom they either rented the land, held it in copyhold, that is by custom of the manor, or in the case of a few, by freehold.

For all of them, life was made no easier by the fact that turbulence and lawlessness, both nationally and locally, were rife. Corruption was endemic in all strata of society and for the privileged few at the top of the social pyramid it was, by today’s standards, a very small society indeed in which everyone knew everyone else. Yet the peasant’s geographical horizons were very limited and he would typically spend all his life in one region of the country. This was largely the result of lack of transport and a primitive road system which, with the vagaries of climate to which the country was, and is, liable, could result in prosperity in one part of the country and the threat of starvation in another.

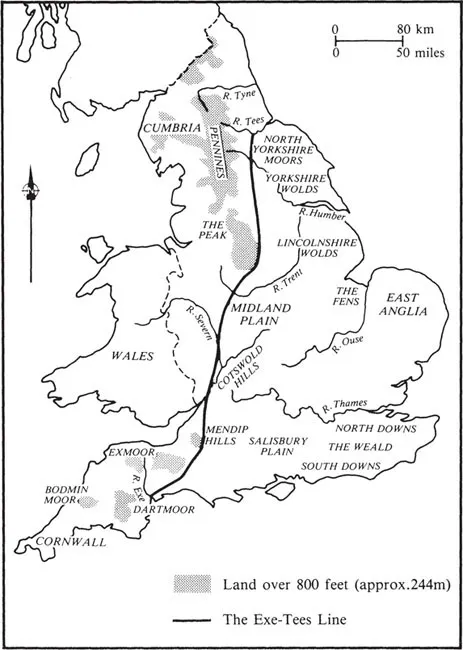

The English countryside was, above all, a mosaic of heterogeneous regions and of great diversity within those regions. In broad terms, the physical characteristics of the country created two principal divisions, as they still do today, between the lower-lying south and east and the hillier north and west, either side of the geographer’s line drawn between the River Exe in the south-west and the River Tees, in the north-east (Figure 1). To the north and west of this line was the ‘upland zone’, with its cooler and wetter climate, its relatively thin soils, and its large expanses of moorland, mountain and fell separated by only relatively few areas of flatland suitable for cultivation. Here, grass was by far the most important crop and pasture farming was dominant. For the most part, settlement consisted of scattered hamlets and isolated farmsteads. Quite different was the ‘lowland zone’, lying to the south and east of the Exe-Tees line. Here mixed farming in which grain was cultivated and livestock kept was dominant. Settlement was mainly in the form of nucleated villages, and large, open fields were widespread.

However, within these two broad areas considerable variations were to be found, the product of the complexity of relief, aspect, soil and micro-climate, which are more characteristic of England than perhaps any other country in the world. Added to this complexity were the local differences brought about by human and historical factors. This resulted in an enormous variety of field systems and agricultural organisations which led Postan to contend that

Figure 1 Upland and lowland England

it is even more dangerous to generalise about the organization of medieval agriculture than about its physical and demographic background. The rules and institutions which regulated medieval agriculture and ordered rural society differed in almost every particular from place to place as from generation to generation.1

Moreover, the identification and interpretation of the main features of the English countryside in all its regional variation at a particular date in time like 1400 are made no easier by the relative paucity of documentary and map evidence. Nor is it to be supposed, of course, that the year 1400 has any particular significance except in the statistical sense of marking the commencement of a new century. The English countryside then, as now, was evolving and changing, though, in a society of relatively primitive technology, the rate of change was slow. Nevertheless, the previous fifty years or so had witnessed very considerable developments in the agricultural economy of the country which by 1400 were affecting the landscape considerably. These developments will be analysed more fully later in the chapter. In the meantime, it is possible to make some reasonably valid generalisations about the nature of the agricultural landscape at the beginning of the fifteenth century. By and large, the country was divided into two main forms of agricultural economy, determined mainly by relief and soil conditions. These were the ‘fielden’ or ‘champion’ areas in which arable farming largely prevailed, and the ‘forest’ or wood-pasture and upland areas, where pastoral and dairy farming predominated.

The ‘fielden’ form of agriculture, in which the plough predominated, extended over large parts of lowland England, especially in the fertile Midland plain, between the Malverns, the Chilterns and the Fens, but also with many extensions to the north, south, east and west. In these areas, the basic field system was that which is generally known as the open-field system. However, in one sense, the term ‘open fields’ is a misnomer in that most of them were not, technically speaking, ‘open’, as their external boundaries were surrounded by fences or hedges. Moreover, the term has sometimes been used as a synonym for common fields, that is fields subject to common rights or communal management, and sometimes as a description of fields, which although divided into strips, were not communally farmed. For these reasons, it has been suggested that the term ‘subdivided field’ rather than ‘open field’ would be more appropriate,2 in that it could be applied to both types. However, because it has been widely used for a long time and because it is more generally understood, by the layman if not the academic historical geographer, the term ‘open field’ will be used in this book, to connote both of the meanings described above.

The landscape of the open fields was entirely different from the field system which we see today over much of central England, the regular hedged and fenced fields which are largely the product of the period of parliamentary enclosure in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The older medieval system still shows through the contemporary landscape and substantial fossilised remains of its characteristic ridge and furrow (Plate 1) have been, and are being, identified and mapped all over the country. In the late Middle Ages, much cultivation was still being carried out in great fields, often several hundred acres in extent. They were unbroken by hedges, walls or fences, except where the fields abutted on a road or any areas from which animals might stray. In the latter case, fences of wooden stakes interlaced with tree branches would be erected between seed-time and harvest to contain the animals. Once the harvesting was completed, the livestock would be released from their pounds to feed on the stubble.

The major characteristics of these great fields were the high ridges and furrows, formed by centuries of ploughing along the same lines, and the pattern of ‘strips’ or lands into which they were divided. These were plainly visible at most times of the year but, in late summer when the crops were high, the open fields were like an undulating sea of waving golden corn. It was for the most part a ‘busy’ landscape, like a Breughel painting, peopled with peasants at work in the fields and richly endowed with flora and fauna. In these as in most other parts of the country, the characteristic unit of social organisation was the manor. The manor was an essential unit of landholding with legal, political, social and economic connotations. It was an estate held by a lord, who might be the crown at one extreme or a simple knight at the other. It might be small or large, it might be part of a large holding of many manors held by a great landowner or it might be the sole possession of a single landowner, and it could comprise several villages or only one. It consisted of the lord’s demesne land, that is the area traditionally reserved for his own occupation, and a variety of customary holdings, freeholdings and tenancies. The lord’s demesne typically occupied about one-third of the whole cultivated area and comprised strips in the open fields and an area around the manor house. The lord of the manor also held the residual ownership of woodland, pasture and fisheries, the use of which was shared with the tenants. Beyond the open fields lay the common waste land on which the manorial peasants grazed their animals. Rights to use the common were carefully regulated and only ‘commonable beasts’ – oxen and horses used to pull the plough and sheep whose manure was highly valued – were normally allowed there. The manorial meadow land also made an important contribution to the agricultural economy; normally, it was fenced off in separate lots and each peasant had a share of the valuable hay crop to feed his animals. Animals were indispensable to the peasant. His horses and oxen went with him to the plough and drew his carts, his cows provided him with milk, butter, and cheese, his sheep with wool for his clothes, and his swine with meat.

Plate 1 Brassington in Derbyshire: the fossilised remains of the ridge and furrow of the open fields, which stand out clearly under a light coating of snow. The older pattern of ridges runs through the later rectangular fields superimposed on them by enclosure

In a typical medieval manor, there were three great open fields, though two, four, five or even six or more fields were not uncommon. The peasants held strips of land scattered over the big fields, sharing areas of good and poor soil alike, forming a complex pattern of holdings made up of blocks which might follow some minor topographical feature or be based upon agreement between earlier settlers. In some parts of the country, the boundaries of the strips were marked either by narrow turf ‘baulks’ or tradeways, which have survived in places as green ways or just by wooden posts and stones, but these seem to have been the exception rather than the rule. The strips themselves were grouped into furlongs, known also as ‘shots’, ‘flatts’ or ‘wongs’ in some parts of the country. Technically, the furlong was not a standard unit of length, but merely a ‘furrow long’, and consequently varied considerably in size even in a single manor. The fields were communally farmed insofar as they were treated as one unit, subject to the same rotation, ploughed as one piece with teams of oxen or horses, sown at one time and harvested at the same time. However within the communal system, each peasant and his family worked his own strips, more or less efficiently than his neighbour, and the harrowing and sowing, weeding and tending of his strips, collectively known as his ‘shot’, were his own responsibility.

The chief crops grown in the great fields were wheat; peas, beans and vetches; barley; and oats and rye. Modern root crops were unknown so that the only way of maintaining the fertility of the land, in addition to the application of the modest quantities of animal manure that were available, was a primitive form of crop rotation. In a typical three-field manor, in any given year one field might be sown with winter wheat, one with barley planted in the early spring, and one left fallow. Fallowing was important for another reason, namely because it was one of the effective methods of cleansing land of weed growth. Except for certain areas near large markets, such as London, very little agricultural specialisation occurred and the invariable crop was grain for consumption in the villages and for sale in local markets. This lack of regional specialisation was probably because roads were inadequate and the cost of transportation was too high.

The centre of settlement, indeed the only settlement, within the typical manor was the village, consisting of little more than a single street of small timber-framed, wattle-and-daub houses or crude huts in which lived the peasant families who worked the land and from which they set out the short distance to the fields each morning and to which they returned each evening. The only substantial buildings were the church, built of stone, and the manor house, timber framed or where freestone was easily available, also built of stone. The village might vary in size from 50 to perhaps 500 people and in the fielden parts of the country was usually ‘nucleated’, that is of a compact design.

The full extent of the manorial system described above has been, and remains, the subject of much research, but in 1400 was certainly widely established in central England, especially in Berkshire and Oxfordshire, Warwickshire and Northamptonshire, Middlesex and Buckinghamshire, and Leicestershire and Nottinghamshire. The most famous contemporary relic of this system is at Laxton in Nottinghamshire where a virtually complete open-field system still operates (Plate 2).

Plate 2 Laxton in Nottinghamshire: a ground-level view of part of one of the great open fields

This ‘classical’ system of open-field farming was also to be found in other parts of England, such as the Welsh marshes. It was well developed in Shropshire, for example, where every hamlet in the Hundreds of Ford and Condover, respectively west and south of Shrewsbury, had its own set of open fields.3 In this part of the country, as in Midland England, the open fields formed islands of cultivation surrounded by extensive stretches of waste and woodland. Indeed, the only part of Shropshire where no open fields were to be found was in the north-west of the country near Oswestry where the settlements consisted of isolated farmsteads rather than nucleated villages.

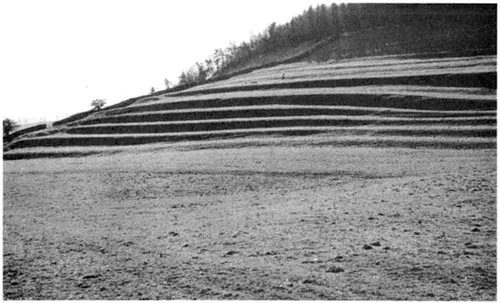

In other parts of the country, marked regional variations of the ‘classic’ open-field system existed. In parts of western England, for example, where Celtic or Romano-British fields and boundaries had survived into post-Roman times, these had been adapted to the open-field system. These Celtic fields were rectangular and normally smaller than the Midland open fields because of the different physical and soil conditions which led to their creation. Consequently, when they were subdivided into blocks or strips, the resulting furlongs were of a different size and shape. Similarly, in the upland parts of central England where pastoral farming predominated, such as the Cotswolds, in the chalk downlands of south-east England, in the uplands of northern England, and also in areas such as Essex, Hertfordshire, Cambridgeshire, Staffordshire, Cornwall and Herefordshire, terraces known as strip lynchets (Plate 3) were commonly found on the steep hillsides. These terraces represent an extension of the open-field system on to steep ground at a time when the more easily worked land was in short supply, as in the thirteenth century.

The normal method of land inheritance in England was, and remains, by primogeniture, that is the succession of the eldest son on the death of his father. In parts of south-east England and East Anglia, however, a system known as partible inheritance was common during the Middle Ages. This involved dividing the land equally between all the male heirs and, in parts of Kent and Suffolk, for example, resulted in a curious pattern of small block strips, not always cultivated or grazed communally, mixed up with areas of enclosed fields.

Plate 3 Strip lynchets at Marske, near Richmond in Yorkshire

Another variant on the ‘classical’ open-field layout was that which was found in the East Riding of Yorkshire, in the Holderness area. Here the manors normally consisted only of two open fields and many of the strips within the fields were very long, often extending for more than a mile, from one field boundary to another. There were fewer furlongs than in the normal open field and the strips lay parallel throughout the larger part of the field. In parts of south-west England, on the other hand, the open fields presented quite a different appearance. In the uplands of west Somerset and in mid-Devon for example, the arable land lay in strips within a multiplicity of irregular, small fields which were determined largely by the uneven nature of the terrain. The fields were often bounded by massive hedge banks which provided both shelter from wind and rain for crops and...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Illustrations

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- 1 The English countryside in 1400

- 2 Sheep or men? The cultivated landscape in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries

- 3 Agricultural improvement: the cultivated landscape in the seventeenth century

- 4 Settlements and buildings in the countryside

- 5 Woodland: forests, chases, parks and gardens

- 6 Industries in the countryside

- 7 Roads and rivers: movement in the landscape

- 8 The English countryside in 1700

- Further reading and references

- Index