Introduction

It has been argued that Africa is a continent full of surprises. Looking at the bigger picture of Africa also reveals some surprises. For instance, if Africa were a single country according to World Bank data, it would have had more than $998 billion total gross national product (GNP) in 2006 and subsequent years (Mahajan, 2009; World Bank, 2014). The African continent is endowed with several natural resources. The continent’s mineral reserves rank first or second for bauxite, cobalt, diamonds, phosphate rocks, platinum-group metals (PGM), vermiculite, and zirconium. Many other minerals are present in quantity. The 2005 share of world production from African soil was bauxite 9%; aluminum 5%; chromite 44%; cobalt 57%; copper 5%; gold 21%; iron ore 4%; steel 2%; lead (Pb) 3%; manganese 39%; zinc 2%; cement 4%; natural diamond 46%; graphite 2%; phosphate rock 31%; coal 5%; mineral fuels (including coal) & petroleum 13%; uranium 16%. (Yager et al., 2007; World Bank, 2014). However, there is much more to the business opportunities than natural resources. Although petroleum production has captured the attention of the media, a company called Bidco Refineries in Kenya has created a cooking oil business worth more than US$160 million (Mahajan, 2009). The previously listed mineral resources and agricultural products constitute the basis for local businesses, multinational corporations, and informal sectors’ activities in the African continent.

Another important trend in business and government relations in Africa is that farmers, entrepreneurs, and miners have all collaborated to promote exports. In addition, groups of African countries have formed numerous trade blocs, which include the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa, the Economic and Monetary Community of Central Africa, the Economic Community of Central African States, the Economic Community of West African States, the Mano River Union, the Southern African Development Community, and the West African Economic and Monetary Union. Algeria, Libya, and Nigeria are members of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC). The African Union was formally launched as a successor to the Organization of African Unity in 2002 to accelerate socioeconomic integration and promote peace, security, and stability on the continent (World Bank, 2014; OECD, 2010). Despite these initiatives, most African countries’ governments have not done enough to promote small scale industry as either a complement or an alternative to large-scale modern manufacturing. Advocates of small industry promotion promise a wide range of benefits, including accelerated employment creation, income generation for the poor, dispersal of economic activity to small towns and rural areas, and mobilization of latent entrepreneurial talent (Johnson & Turner, 2016). It is also very important to argue at this junction that support for small enterprise and the informal sector could help African countries create a wider base of political support for capitalism and free-market policies.

As more businesses target their share of the African economy, there is ample need to critically examine the success factors in and obstacles to operating in the various African countries economies. By creating a positive business environment, providing the right tools for entrepreneur-ship and trade, and offering private sector partnership with government (Johnson & Turner, 2016), African nations could open the door to their people to pursue self-development. There is no development approach that is more edifying to person, and in turn, more durable in result, if there are no skilled entrepreneurs (Natsio, 2007; Johnson & Turner, 2016). In addition, several African countries businesses still do not have a clear pathway to profit. Private investors are not motivated enough by the government to meet the poor people needs in Africa (Nafziger, 1993; Sandbrook, 1993; Rangan et al., 2007). According to Rangan et al. (2007), many successful cases of business provision to poor consumers owe their profitability to enlightened government policies in some countries that enable adequate return of investors. In few countries in Africa, such policies seem to have common characteristics. For instance, government may provide just enough incentives to attract the private companies’ entry to develop the infrastructure, but leave it to the businesses to collect the rest of the return from consumers of their services and products (Rangan et al., 2007; OECD, 2010). This very important relationship between government and business in Africa has forced innovative market mechanisms to emerge in terms of product and service design, on one hand, and delivery and compliance, on the other hand. In addition, in 2005 Europe received 35% of Africa’s petroleum exports; the United States, 32%; China, 10%; Japan, 2%; and other countries in the Asia and the Pacific region, 12%. West African countries sent 45% of their exports to the United States and 32% to China, Japan, and other countries in the Asia and the Pacific region. North African countries sent 64% of their exports to Europe and 18% to the United States. Intraregional exports to African countries amounted to only 2% of total African petroleum exports (British Petroleum plc, 2006: 20).

Government, private sector, and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) are essential components of economic development and poverty reduction in African countries. The relationship between these three sectors is also a very important source of innovation and employment generation (Griffin & Moorhead, 2014; Dibie, 2014a). Government has always been an influential actor in the economy of several African countries. This is because they own many public corporations and are able to enact public policies that assisted economic growth as well as promoted industrial development or the control of inflation and unemployment. The assessment of activities of government in several African countries in the past few decades could help readers better understand contemporary proposal for government action. In addition, an awareness of the changes that have occurred in business organizations will also help us appraise the corporate innovations that are taking place in the African continent.

The center objective of most African countries economic policy is to improve economic stability and welfare of its citizens. To successfully achieve these economic policies, five goals are important: (a) the creation of economic growth; (b) stability of prices; (c) positive balance of trade; (d) management of deficits of trade and debt; (e) and full employment. Economic growth is vital to nations in order to reduce poverty rates and unemployment, increase public resources, and avoid inflation (Dibie, 2014a; Pettinger, 2008). Price stability is the reduction of inflation or deflation of products and services, and reaching this goal is important to prevent the redistribution of wealth of citizens. Positive balance of trade promotes the act of exporting more than is imported, a goal that is very much interconnected with international economics. In addition, a well-regulated and vibrant competitive private sector can also empower poor citizens by providing them with better goods and services at more affordable prices. In the past two decades, government in several African countries have paid more attention to fostering private sector development as a major instrument of their national sustainable development strategic plan (OECD, 2010; World Bank, 2014).

Further, while ethics have long been of relevance to government and business relations in sub-Saharan African countries, what seems like an epidemic of ethical breaches in recent years has placed ethics in the lower mainstream of managerial responsibility both in the public and private sectors. According to Ferrell et al. (2015), two special aspects of government and business relations that have not taken increase importance are corporate governance and corporate social responsibility. Another significant area of government and business relations today involves employment relationships. Employment knowledge in the private sector is those values that are frequently transferred from the business sector to government agencies and vice versa (Geuras & Garofalo, 2010). For example, knowledge workers are those who add value to an organization because of what they know. How well governments in African countries are able to regulate businesses is seen as a major factor in determining how successful and ethical the economy may be in the future.

This chapter provides an overview of the nature of the economy of most African countries. It also investigates how the government of some African countries regulates business to preserve competition and protect consumers and employees. In some African countries, the national and regional governments also intervene in the economy with laws and regulations to promote competition and protect the environment, consumers, and employees. When necessary, the governments often would take steps through its central bank to minimize disruptive effect of economic fluctuation to spur growth so that consumers may spend more money and businesses may hire more employees. The chapter also describes how the governments of some African countries control the activities of businesses when the economy expands too much by raising the interest rate to discourage spending by businesses and consumers. It also examines how privatization, outsourcing, and contracting out are a practice of hiring other business organizations to do the work previously performed by the government. This practice is an increasingly popular strategy because it helps government to focus on their core activities or functions. A central issue in the past five decades revolves around the fact that rapid changes in government and business relationship, type of regulations policies, and the state of the economy pose unsurpassed difficulties in keeping accurate track of government’s fiscal policies. It recommends that managers in government and business institutions in sub-Saharan Africa should be cognizant of both primary and secondary dimensions of diversity, as well as the many benefits to be derived from having diverse workforces that could propel sustainable development. Sustainable development cannot be achieved if there is a poor or weak government and business relations in any African country.

Globalization

Globalization is defined as the process of interconnecting the world’s people with respect to culture, economic, political, technological, and environmental aspects of their live (Dibie, 2014a; Lodge, 1995). According to Griffin et al. (2017), a global perspective is distinguished by a willingness to be open and to learn from the alternative systems and meanings of other people and cultures, as well as a capacity to avoid assuming that people everywhere are the same. Globalization is playing a major role in the environment of the economy of many countries in sub-Saharan Africa. The globalization trend started soon after World War II. Managing in a global economy poses many different challenges and opportunities. An important consideration is how behavioral processes vary widely across cultural and national boundaries. For instance, a person with a global perspective tends to view the world from a broad perspective, always seeking unexpected trends and opportunities (Kedia & Muhkerji, 1999; Rhinesmith, 1992). In addition, people with global perspectives are more likely to see a broad context and accept life as a balance of conflicting forces.

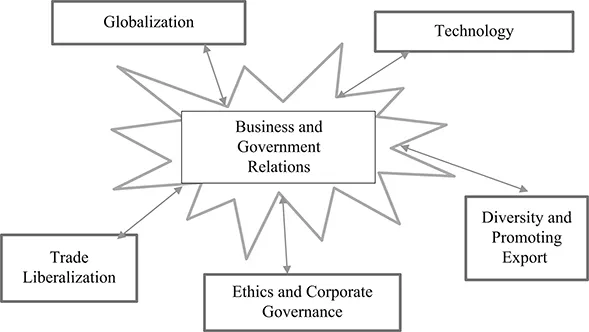

Greenberg (2013) contends that the trend toward globalization has been widespread in past few decades as a result of three important forces. The forces include the following: (1) Technology has drastically lowered the cost of transportation and communication, thereby enhancing opportunities for international commerce and economic growth in many countries. (2) Globalization has also resulted to the enactment of new laws that have liberalized trades in many countries in Africa and around the world. It will be recalled that previously laws restricted trades, and most transactions were based on the principles of comparative advantage. (3) Globalization has also galvanized developing countries to seek to expand their economies by promoting exports and opening their doors to foreign companies seeking investment. Therefore, it could be argued that international trade is the major driver of globalization, while the primary vehicles are multinational corporations that have established more than 30% of their operations all over the world (Dibie et al., 2015; Greenberg, 2013; Daniels et al., 2011). Figure 1.1 shows the five changing environmental factors that have affected business and government relations in Africa.

Figure 1.1 Changing environmental factors of business and government relations in Africa

Globalization just like what is proposed by the modernization theory requires the emergence of a rational and industrial individual or corporation that is receptive to new ideas, acknowledges different opinions and is punctual and optimistic, and believes that rewards should be distributed on the basis of universalistic rules. Therefore, globalization practice could be argued to offer a better but still partial foundation for sustainable well-being for developing countries in Africa. For instance, the top nine largest multinational corporations in 2015 were forms from industrial countries. These multinational corporations include Royal Dutch Shell, Walmart Stores, ExxonMobil, British Petroleum, Sinopec (Chinese Petroleum and Chemical Corporation), General Motors, Toyota, and Ford Motors (Griffin et al., 2017; Fortune, 2011). It is important to note, however, that in the past three decades, despite the positive benefits of globalization, the number of experts throughout the world has risen, fallen, and changed direction, along with shifts in economic development throughout the world. At the same time, shrinking economies sometimes leave experts without jobs in their newly adopted countries (Greenberg, 2013). On the other hand, those working in another country as a result of globalization are exposed to different cultures. Difference in culture could lead to cultural shock; this means that people’s recognition that others may be different from them in ways that they never imagined, and this takes some getting used to. According to Nelson and Quick (2013), the feelings of cultural shock are inevitable, although some degree of frustration may be expected when a person first enters a new country. However, the more time a person spends learning the new culture, the better they will come to understand and accept it (Janssens, 1995). Therefore, the fact that the world’s economy is global in nature suggests that highly parochial and ethnocentric views have no place in business and government relations in respect of international trade. Despite the technical difficulties associated with globalization, government agencies must work on appropriate guidelines to ensure that their respective countries do not miss out on the benefits of globalization. At the same time, multinational and domestic companies in Africa need to develop internal guidelines, training, and leadership to ensure compliance of government regulations.

As a result of globalization, the volume of government and business relations has grown significantly and continues to grow at very rapid pace. There are five basic reasons for the growth of government and business relations in sub Saharan Africa:

- Many local organizations have become international and have to seek approval to enter foreign and domestic markets;

- Communication and transportation have advanced pragmatically over the past several decades;

- Many local businesses have diversified into other markets to control costs, especially to reduce labor costs;

- Government and business relations have grown due to new regulatory policies; and

- In several countries government has increase the privatization of previously owned public corporation. In some cases the governments have contracted out services to businesses and nonprofit institutions or nongovernmental organizations.

(Greenberg & Baron, 2012; Griffin & Moorhead, 2014)

It is very important to observe that as a result of globalization trends and multicultural nature in Africa, business managers are increasingly required to have a global perspective and supportive set of skills and knowledge that are highly effective (Wankel, 2007; Levy et al., 2007). A related business challenge that is relevant to globalization is adopting broader stakeholder perspective and looking beyond shareholder value. This challenge calls for social responsibility. According to Nelson and Quick (2013), social responsibility requires businesses to live and work together for the common good and value of human dignity. Griffin et al. (2017) contend that when social responsibility issues involve the creation of a green strategy that is intended to protect the natural environment, it is often called corporate sustainability. In the past two decades, multinational corporations working in Africa are now increasingly interested in balancing their financial performance with their employees’ quality of life, and improving the local community and brother society (Griffin et al., 2017; Daniels et al., 2011).

Some scholars have argued that globalization can be harmful to the poor if it opens markets for agricultural products from developed countries to African nations. Such...