![]()

1

Introduction

Reidar Aasgaard and Cornelia Horn, with Oana Maria Cojocaru

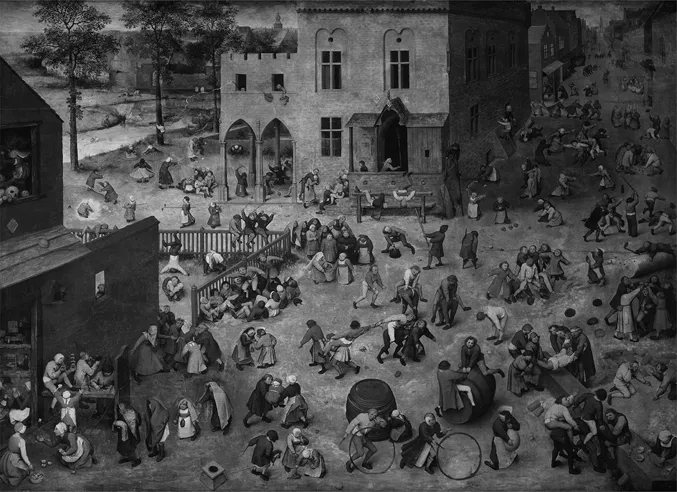

In 1560, the then thirty-five-year-old Dutch painter Pieter Bruegel the Elder painted the picture Children’s Games, which is reproduced here (Figure 1.1).1 It is a remarkable painting. For at least two reasons, it is of particular interest for this book.

First, the picture portrays a vast number of children, about two hundred, of both genders, of varying social standing, and belonging to different age groups, from early childhood to late teens. Bruegel shows them as being engaged in a wide variety of games, nearly eighty in total. Through its representation of a large number of children, the painting makes visible what other sources from earlier times mostly conceal – namely that in the ancient world children were omnipresent nearly everywhere. In premodern times, they would have made up about half of the population.2

As far as we know, never before had so many children been gathered together on one canvas, and certainly they had not been represented as being occupied with such playful activities. Although the painting was made at a date that is slightly later than the period that is our concern in this book, many of the games played by the children in the painting had been known already from a thousand or even two thousand years earlier: archaeological remains of knucklebones, depictions of youngsters rolling hoops, and records of children playing role games have come down to us from the very beginning of this long stretch of time – and a large number of the games are still played today. What we see here is children’s culture in full bloom. If we could look further back, about one or two millennia from the time depicted in Bruegel’s painting, we would probably observe much the same: although the clothing or playthings might have had a somewhat different shape, the overall scene would not be fundamentally different.

The second point that makes the picture very special is grounded in what is not shown, but what we might expect to have been present: adults are nearly missing from the painting. Indeed, we see a scene that almost exclusively features children.3 Nevertheless, adults are still prominently present in the picture. First, they are there through the painter’s perspective which identifies with that of an adult observer. The artist who arranged the scene, who may or may not have been Bruegel himself, selected the kinds of children and situations to be represented, painted the buildings which had been constructed by adults, and chose the perspective from which the cityscape was to be viewed; it is not a coincidence that the long street to the right leads up to and ends at a church, and that the city square to the left opens onto a rural landscape with trees and water. Although Bruegel decided to remove the grown-ups from the scene, the imprint of the adult world is present everywhere, even down to the role games which many of the children in the picture play.

Figure 1.1 Children’s Games, painting by Pieter Bruegel the Elder (ca. 1560).

Furthermore, the perspective taken by adults is also present in the audience of the painting, in those who commissioned it, and in those who would have the opportunity to see it. Not much is firmly established here, but it is likely that the painting was produced to fit in with contemporary ideas and ideals about childhood and about children’s education in an urban, middle-or upper-class merchant milieu in Antwerp.4 Perhaps the painting hung at an appropriate place, maybe in a private space, such as a dining room or in one of the many private secondary schools established at the time in this city.5 Whether it was indeed ever placed where children could see it we do not know. What we see in the painting, then, is some kind of a children’s world, but it is a world that is still viewed through the eyes of adults and shaped by adult attitudes of what childhood was about, or what it should be about.

The matters briefly reflected on here are among the topics we shall deal with in this book. In this introductory chapter, we will (1) present the general motivations and background for the volume, (2) set out its rationale and distinctive profile, and (3) give a survey of what we regard as some of the book’s main contributions to the study of childhood in history.

Motivations and the state of research

The past two decades have witnessed a steady growth of interest in the lives of children and in understanding the experience of childhood in history. At present, this interest is flourishing both within academic research and among the general public. The reasons for this increase are many: over time, there has built up a robust awareness of the fundamental importance of infancy and childhood for the life-long development of human beings. At the same time, an equally strong attentiveness to the vulnerability of children has developed, dependent as they are on adults for their survival and thriving. In a world marked by serious challenges, including ecological crises and increasing social and economic disparities, securing and strengthening the well-being and the rights of children are tasks that are ever more necessary. Indeed, acting on behalf of children has become a central social and ideological concern for many.6 The great social and cultural diversity we experience in our modern societies has made us aware of how the differences among us have been shaped by the past, by the various ethnic, religious, ideological, and other traditions within which each of us has grown up. It is clear to many that, as human beings, we are not only biological or social beings but also historical beings.

These are important reasons why the study of children and childhood has become a point of focus in historical research. In addition, however, we have become alerted to the simple fact and paradox that, whereas children at any time in history have constituted a large percentage of every population, their lives and living conditions have hardly been studied. There has been, and still is, a glaring discrepancy between the number and importance of this group of human beings and the extent to which they have been given, or rather have not been given, attention in our studies of the past. In order to do justice to this subgroup of humankind and this area of research, but also in order to advance historical research in general, obligated as we are to produce a nuanced and adequate portrait of the past, a deeper and more extensive investigation of children’s lives and experiences is required. The need for further study is obvious.

One final rationale for inquiring into historical children and childhood to be mentioned here is that such an inquiry informs us about other related and crucially important matters. The ways in which any society deals with its less privileged or more vulnerable groups tell us a lot about this society in general: its attitudes, values, and priorities – in fact, its perceptions of the human being in general, and the basis and nature of human dignity. The study of historical children and childhood is an inquiry into the fundamentals of anthropology, of ideas about the human being and her or his status as a living creature. How children are viewed and treated serves to uncover value conflicts and power struggles within society at large. For instance, the status allotted to the infant, whether unborn or newborn, compared to the adult reflects perceptions of what constitutes the value of a human being. The varying goals that are set up for the formation and education of children mirror different, and often conflicting, ideas of what or how a human life should be, or what kind of ideals one envisions for society as a whole. Inquiring into historical childhood is an especially appropriate way of approaching the perennial and essential question that no one can avoid in some form or another, namely the question of what it is, in our own view and in that of others, that makes humans – each of us – human.

Some of the works that have been published so far are especially apt as guides to the earlier developments and to the present state of research on children and childhood within the history of European civilization, which is the main sphere for this volume. One of these works is the comprehensive six-volume A Cultural History of Childhood and Family (2010), edited by a diverse set of scholars. The work presents historical overviews of a broad range of topics, such as cultural, social, economic, and political issues.7 Another volume, The Routledge History of Childhood in the Western World (2013), edited by Paula S. Fass, also gives historical surveys, with its main focus being on the modern period.8 An important early, but still valuable, work is The Child in Christian Thought (2001), edited by Marcia J. Bunge, which deals with central historical figures and movements in Christianity from the New Testament onward.9 The Palgrave Handbook of Childhood Studies (2009), edited by Jens Qvortrup, William A. Corsaro, and Michael-Sebastian Honig, presents surveys of social-scientifically oriented research, and of central areas and approaches to the study of childhood, including the history of childhood. One might also refer to the historical articles of the “Childhood Studies” section of the web-based Oxford Bibliographies, edited by Heather Montgomery, which give systematic overviews, summaries, and assessments of a great number of central scholarly contributions to the field.10

Within the area of childhood history, there has been a marked, and growing, interest in research on premodern history. This has been particularly the case with the Roman period, early Christianity, and the Middle Ages. Research on children and childhood in the Middle Ages was the first area to emerge, largely as a reaction to the very influential but much-criticized book by Philippe Ariès, Centuries of Childhood (1962).11 During the last fifteen years, however, research on childhood in the Roman Empire and early Christianity has bloomed, with increasing attention more recently, within the last decade, to late antiquity. Some research – with a few particularly prominent works – has been done on classical Greece, the Hellenistic period, and the Byzantine world, but to a considerably less extent.12 Among important studies in the ancient and medieval worlds which summarize the state of research, one should mention the monograph by Mark Golden, Children and Childhood in Classical Athens (2015, second edition), and the anthology edited by Judith Evans Grubbs, Tim Parkin, and Roslynne Bell, The Oxford Handbook of Childhood and Education in the Classical World (2013).13

Within the Christian tradition, another book edited by Bunge, The Child in the Bible (2008); a volume edited by Cornelia Horn and Robert Phenix, Children in Late Ancient Christianity (2009); the monograph by Cornelia B. Horn and John W. Martens, “Let the Little Children Come to Me”: Childhood and Children in Early Christianity (2009); and Odd Magne Bakke’s When Children Became People: The Birth of Childhood in Early Christianity (2005) present broad surveys of this field of research.14 For late antiquity, including Christianity, the volumes edited by Christian Laes, Katariina Mustakallio, and Ville Vuolanto, Children and Family in Late Antiquity: Life, Death and Interaction (2015), and by Christian Laes and Ville Vuolanto, Children and Everyday Life in the Roman and Antique World (2017) have updated surveys of research and present recent advances, trends, and methodologies.15

Writing children’s history or a history of childhood?

The title of this volume, “Childhood in History”, needs some clarification. It can be interpreted in at least two ways: it can refer to perceptions of children and childhood on the part of adults – that is with the focus being on adults’ attitudes, mentalities, conceptions, and ideals. Or it can refer to the history of children –that is it can identify a history that deals with the lives of the children themselves, such as their living conditions, roles, and experiences, and with the social and cultural conditions and environments they encountered in the family and in society. Whereas the latter (to oversimplify) is concerned with “realities”, the former deals with “ideas”.

Clearly, however, it is not possible to make a clean separation between these two aspects. For example, the attitudes of adults toward children will influence how adults treat them, and consequently contribute toward shaping children’s lives and even their self-perception. The ways in which children respond to adults likewise impact how adults perceive them and how adults act themselves. Interpreted this way, even “ideas” will form part of what we call reality. Nevertheless, we believe it is generally viable, and for analytical purposes even necessary, to distinguish between the two aspects: seeing children and childhood from the perspective of adults will lead to views that differ significantly from what childhood looks like when it is seen from the perspective of children and of how they experienced their own lives, and not least their relations to adults. The former perspective is shaped in a conversation with ideas reflecting the times and changes with them (Stoic, Romantic, idealistic, etc.); the latter perspective is strongly – but far from exclusively – related to features that are specific to children, such as physical size and ways of reasoning, and the material and social conditions that children at any given time are exposed to, in ways quite similar to other vulnerable individuals and groups in society.

In this book, our emphasis is mostly on ideas about children and childhood. As our subtitle indicates, we focus on “perceptions of children in the ancient and medieval worlds”. Our aim is to trace significant ways of thinking about children and childhood through this long historical period, with attention to matters such as the interplay between material and social conditions and cultural and ideological conceptions, the interchange of different religious traditions, and continuities and changes, but also to how these patterns may have shaped children’s lives. However, because the two aspects intersect in various ways, we shall later come back to a couple of examples of this. At any rate, our main focus in the following chapters will be on the “history of childhood” perspective.

The immediate context for our Childhood in History book has been the project “Tiny Voices from the Past: New Perspectives on Childhood in Early Europe” (2013–2017).16 The present book, together with the volume Children and Everyday Life edited by Laes and Vuolanto, is one of the central outcomes of this project. Unlike our book here, however, the emphasis of their volume is on the lives of the children themselves. Thus, the two books serve to illuminate the study of children and childhood in history from different yet supplementary perspectives.

This difference in emphasis is not merely a matter of editorial choice. It arises almost necessarily from the difference in methodological approach and in the material studied. Whereas the contributions in Children and Everyday Life consider more prominently societal and archaeological evidence of various kinds, the chapters in our volume focus more on literary and related texts. Both material evidence and textual evidence preserve traces of children’s lives, although children and concerns about them appear to have had less access to texts, and less opportunities to shape them, than is the case with material culture. Clearly, some objects and some texts show an awareness of children and of the life stage of childhood – or at least, they were almost unintentionally produced under the influence of thoughts and considerations about children. These, however, had a greater impact on the production of the material enviro...