- 188 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This book examines how readers and novelists alike have used maps, guidebooks, and other geographical media to imagine and represent the space of the novel from the mid-nineteenth century to the present.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter One

On Getting Oriented

“A good map or plan … saves many a line of description.”

James Muirhead, “Baedeker in the Making”1

How do we orient ourselves in a novel? Although novel readers seem to automatically process directions as they read, very few have stopped to consider what this activity actually involves. Getting oriented might seem simple enough, but just think about how quickly an unrecognizable street sign can throw us off track. Readers often feel disoriented when they are unable to imagine the location of an individual street sign or place name in relation to larger spatial totalities like the neighborhood, city, country, or continent. Over the past one hundred years or so, the study of orientation has largely been restricted to the fields of psychology, geography, and urban theory. It has not, at first glance, been a thing that concerns the study of the novel. In the past few decades, however, questions about orientation have been integral to discussions of novelistic space. Think of Raymond Williams’s “knowable community,” Edward Said’s “imaginative geography,” Frederic Jameson’s “cognitive mapping” (taken from the urban theorist Kevin Lynch), and Franco Moretti’s “literary geography.”2 Each of these critics deals directly and indirectly with the ways that novels orient readers by producing and circulating forms of geographical knowledge. Despite their different approaches and conclusions, they all emphasize that spatial representations in the novel are ideologically charged. Readers do not simply see the world: they get a distorted, biased glimpse rooted in a particular time and place.

Nowadays, critics are suspicious of novelistic space. There is no longer the assumption that spatial representations derive from a set of neutral and value-free literary conventions reflecting an innocent and timeless world-view. Representations of the city, country, landscape, and the nation conceal a complex network of social relations and historical processes that impact how readers imagine the world inside and outside the novel. Still, in discussions of novelistic space critics, including the ones mentioned above, have chosen to emphasize the idea that the novel produces space and readers consume it. Little consideration has been given to the fact that readers also produce space. Although we can only wonder what nineteenth-century readers actually saw when reading novels by Thomas Hardy, Joseph Conrad, Emile Zola, or Charles Dickens, it is possible to construct a material history of this readerly production of space from the various literary maps and literary guidebooks they left behind.

In this chapter, I am interested in the way that readers for the past century or so have used maps in response to, and partially as a way to deal with, realist representations of the city. The realist novel brought with it an exponential increase in the number of real street signs and place names. What do they do? Why are they there? Although with the help of Bakhtin, Moretti, and others, we have come a long way toward understanding how topographical details generate narrative design, it is less clear how they affect readers. As I hope to demonstrate in this book as a whole, the tradition of literary mapping is more than a knee-jerk reaction to realist space or an aide-mémoire. It is deeply grounded in the belief that novels have the power to orient us in the physical environment. And here this concept of orientation is deeply intertwined with more fundamental questions about spatial representation, the history of cartography, and the disorienting effects of urbanization on the lived environment. As I will discuss throughout this chapter, literary maps enabled readers to deal with the disenchantment of novelistic space between the end of the nineteenth and the beginning of the twentieth century, the harsh reality that the swift pace of modernization could change the physical world and make so many novelistic representations hopelessly outdated.

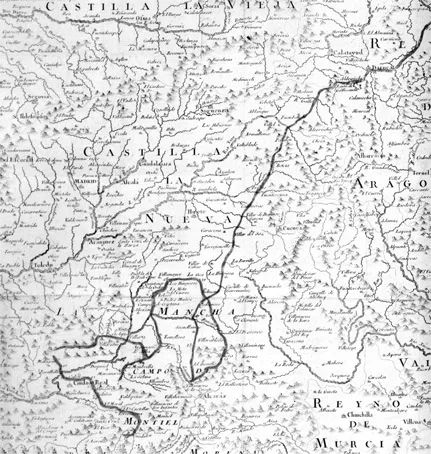

Literary maps became particularly popular at the beginning of the twentieth century, but they were not new. Ever since Don Quixote’s first sally across Spain, novelists and readers have consulted, drafted, and coopted maps as a way to orient themselves (figure 3).3 In one of the earliest known examples, the editors for the third edition of Don Quixote superimposed a squiggly line over a map of Spain to indicate the direction of Don Quixote’s and Sancho Panza’s route between La Mancha and Barcelona. A century or so later, Daniel Defoe, as I mentioned in the previous chapter, attached a barley legible map of the world to the fourth edition of Robinson Crusoe, with a dotted line outlining the course of his protagonist’s ill-fated voyage.

Before going any further, I want to restrict my definition of what makes a map “literary.” The Quixote and Crusoe maps lay out the routes of fictional characters, but it would be difficult to follow the exact route. Practical orientation in these early examples was not really the point. More than anything else, early literary maps were a way to advertise the novel’s realism. No matter how fantastic, surprising, magical, or ridiculous novels may seem, the literary map was a way to stave off the skepticism of readers. Indeed, the “realistic particularity” of space, has always played an important role in the rise of fictional realism.4 Instead of happening in a place long ago and far away, novels have been set in cities, towns, and regions that readers would recognize as real even if they were not exactly sure where to find them.

Figure 3. Map from Don Quixote. From the third edition of Don Quixote for la Real Academia Española.

In an exhibition devoted to literary maps at the Library of Congress in 1993, the curators came up with the following definition:

A literary map records the location of places, associated with authors and their literary works or serves as a guide to their imaginative worlds. It may present places associated with a literary tradition, an individual author, or a specific work. Some maps highlight an entire country’s literary heritage; others feature authors identified with a particular city, state, region. Maps can feature real places connected with an individual author, literary character, or book, such as those featuring Jane Austen’s England, Sherlock Holmes’s London, or the settings in Moby-Dick, or they may show wholly imaginary landscapes such as Oz, Middle Earth, or Neverland.

If this definition is any indication, the literary map can assume a variety of forms. It can provide a biographical chronology, celebrate a nation’s literary past, or trace out a character’s itinerary. Some literary maps are devoted to an individual work, while others bring together a mélange of plots and characters from specific periods and nations.

In the history of literary maps, the Quixote and Crusoe maps are isolated instances. They do, however, presage the emergence of an autonomous genre of literary maps at the end of the nineteenth and beginning of the twentieth centuries, which I will discuss later in this chapter, and the more widespread acceptance of them by critics and publishers today. Publishing houses such as Oxford University Press, Norton, and Penguin regularly include maps in their reprinted editions of the world’s classics to help an audience of global readers locate the main action. What is said in the introduction to the Penguin edition of Zola’s L’Assommoir is typical of the cartographic logic for all of these publishing houses: “Every street through which the characters pass is named; the events of the story can be followed precisely on a contemporary map of Paris … Few writers convey so vivid and immediate a sense of what it felt like to live in a particular place, at a particular moment in history.”5 Even though it may be exciting at times to recognize passing street names as we read a novel, is a cartographic image of the city’s entire layout necessary? Can a map really make us imagine “what it felt like to live in a particular place, at a particular moment in history”? It goes without saying that living in Paris would be quite different from seeing it on a map. Zola may have used real street signs in his representation of Paris, but he conveyed the feeling of living there by using meticulous descriptions of the environment and the living conditions of his characters.

In an effort to keep readers oriented, many of these same publishers often disregard the fact that there are also instances when novelists deliberately disorient readers. Take an example from Honoré de Balzac. In the

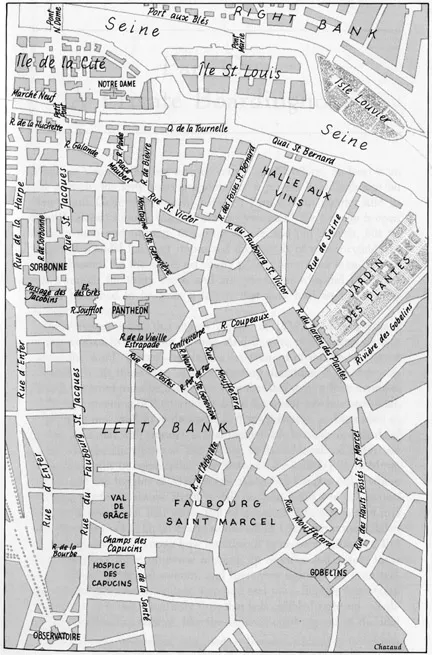

Figure 4. Map: Paris in the 1820s. From Père Goriot, ed. Peter Brooks. Courtesy of W. W. Norton & Co.

Norton Critical Edition of Père Goriot, we find a two-page map of Paris from the 1820s placed immediately before the opening line. No matter how carefully Balzac described the exact location of Madame Vauquer’s celebrated pension (“at the lower end of New Saint Genevieve Street just where it slopes down toward Arbalete Street”), today’s readers are still encouraged to consult the map to get their bearings (figure 4). Lest they get lost too quickly, the editor, Peter Brooks, has even included a footnote on the very first line to guide them: “The rue Neuve Sainte-Geneviève, today called rue Tournefort, is located on the Left Bank of Paris (the southern side of the Seine River) on the edge of the student quarter.”6 Getting lost, in this edition anyway, is not recommended. The street names may have changed in the real city (and the pension bulldozed) long ago, but the location on the map has not.

The concept of “location” is crucial for understanding the relationship between maps and novelistic space. What does it mean to locate particular cities, towns, seas, landscapes, and countries when we read? Here, the definition in the Oxford English Dictionary is useful: “To survey and define the limits of (a tract of land); to lay out (a road); to mark the position or boundaries of, to enter on or take possession of (a land-claim, a gold-mine, etc).” Defining limits, laying out, marking boundaries: locating is a process of negation. You know where you are, in other words, by figuring out exactly where you are not. Rue Tournefort is not in Istanbul, it’s in Paris on the left bank. But is that spatial relationship really enough to locate it? Is spatial approximation ever enough? Can’t rue Tournefort be somewhere around Paris instead of an exact spot in Paris?

Locating the space of novels is an act of translation: street and place names become points on a map. We move from a nonvisual to a visual mode of spatial representation. More often than not, though, literary maps over-rationalize the space of the novel. They want exact not approximate distances and locations. But no matter how hard we try to make the space of the novel legible, spatial imagining is a messy business: signs pop up along the way and we either know or do not know where they belong. The desire to imagine novelistic space on a map is a symptom of not an antidote to estrangement. Part of what made the “reality effect” in nineteenth-century novels so powerful was its uncanny power to convince readers that a single street sign could conjure up an entire metropolis. Rue Neuve Saint Geneviève is not simply in Paris, it is Paris. Although real street signs and place names have this power to enchant us by drawing a link between the fictional world of the novel and the real world it represents, they do not translate so easily over time. Even if the representation in the novel does not change, the readerly perception of it does. Maps become necessary for orienting novel readers, in other words, when novels no longer do the trick.

In the Norton edition I referred to earlier, readers are expected to “locate” Balzac’s Paris on a map: the real space of the city, which no longer exists in the way it once did, and the novelistic description, which does, are secondary. Paris is not, as Moretti has discussed elsewhere, understood as a series of “relations” but locations “as such”: isolated points on a map without any obvious link to the rest of the city.7 To locate does not mean having a general sense of Madame Vauquer’s pension in Paris but an exact spot, an empirical position on a cartographic image. Norton and so many other publishing houses today advertise a mediated form of spatial imagining, one in which the obsolescence of literary description, bound to a time and place, is replaced by the convenient contemporaneity of an image. The space of Père Goriot, they pretend, has an afterlife that not even Baron von Haussmann’s bulldozers could stop.

By locating the main action on a map, though, today’s readers seem to miss the point about the sociality of space. When Balzac used rue Neuve Sainte-Geneviève as the principal street for Père Goriot, he anticipated the fact that many of his Parisian readers, particularly the upper classes from the rive droite, would not know where it is: “A Parisian who gets lost in there, would see only pensions and hospitals, and private schools, only misery and boredom, old age sinking into the grave or happy youth forced into unhappy labor. There’s no more hideous neighborhood in all of Paris, nor, in truth, one so little known.”8 For Balzac, knowing or not knowing the location of Madame Vauquer’s pension was directly connected with one’s place on the social ladder.

Current attempts to map out Père Goriot may make Paris seem more inviting, but they also have the effect of reducing the city’s social complexity. The map orients us, but it also counteracts a socially charged disorientation effect that was integral to the spatial representation in the novel. In his topographical reading of Gustave Flaubert’s L’Education Sentimentale, Pierre Bourdieu provides an alternative mapping of Balzac’s city. He uses the map of Paris as a starting point for an engaged sociological analysis and illustrates how the mobility of characters is directly related to social status.9 Building on Bourdieu’s example, Moretti’s mapping of the nineteenth-century novel in Britain and France also emphasizes the sociality of novelistic space. For Moretti, the map does not simply make us see where the action is set: it enables us to understand “spatial, mental, and social mobility” in the novel itself.10

Literary maps tell us...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction Orienting, Disorienting the Novel

- Chapter One On Getting Oriented

- Chapter Two Melville’s Zig-Zag World-Circle

- Chapter Three Joyce’s Geodesy

- Chapter Four Pynchon’s Baedeker Trick

- Chapter Five On Getting Lost

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Novels, Maps, Modernity by Eric Bulson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Literary Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.