![]()

1Introduction

The future of the city as a collage of pasts

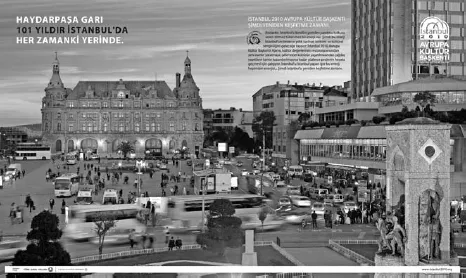

The past circulates in present day Istanbul—not only because historic monuments and artifacts are scattered through the city but also because the past is continuously improvised upon. One of the most striking advertisements celebrating Istanbul’s status as a European Capital of Culture (ECoC) in 2010 inserts the image of Haydarpaşa Train Station in place of Atatürk Cultural Center (Atatürk Kültür Merkezi, AKM) (see Figure 1.1). This ad campaign developed two concepts, one for the domestic audience and another for audiences abroad. Campaign images produced for exhibition outside of Turkey were based on the concept of “situating Istanbul on par with other leading world metropoles” and featured a seductive yet brooding silhouette of the historic city produced by photographer Rainer Stratmann. In contrast, domestic campaign images uprooted well-known monuments and placed them in other, also familiar locations. The concept was, purportedly, to rediscover the city. The spokesperson of the Istanbul 2010 ECOC Agency at the time explained: “We wanted [the residents of Istanbul] to become aware of the city. For this reason, we came up with this concept of re-discovery … We want Istanbulites to recognize the wonders they take for granted.”1 How does such an image, a strange image, actually work? What does it communicate? What are the different ways it could be read?

Figure 1.1 Istanbul 2010 Advertising Campaign image shows Haydarpaşa Train Station in place of Ataturk Cultural Center on Taksim Square.

Produced by advertising agency UltraRPM. İstanbul İl Özel İdaresi.

In order to understand this composite image, a brief story of the AKM, a building around which considerable power struggles have been and continue to be staged, is in order. The AKM was first proposed in the mid-1930s as a performance venue for opera for Taksim Square. After several designs and multiple halts in construction, architect Hayati Tabanlıoğlu designed the final version. Following a fire in 1970, the building was closed and opened again in 1977. In addition to the art galleries located on its top floor, the AKM has halls to stage opera, ballet, theatre, classical music performances, and concerts. It has a commanding position on Taksim Square. Its abstracted façade composition, alluding to a rising curtain, austere massing, elegant modernist detailing, and, most importantly, functional programming, have all aided the building’s association with early Republican-era cultural modernism, though it was built much later. The AKM was closed in 2008, allegedly for maintenance and repairs, but its prolonged closure and rumors of planned demolition have triggered much consternation within the architectural community. Since the mid-1990s, there have been verbal proposals to build a grand mosque on Taksim Square.2 Coupled with the current government’s distaste for and disapproval of Western forms of performance art, the fear of some (and the stated goal of the current President of Turkey, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan) is that the Cultural Center will be torn down and a mosque will be built, changing forever the association of the square with cultural modernism.3

Haydarpaşa Train Station, which was montaged into the location of the AKM in the original photograph, is another controversial site (see Figure 1.2). This train station is the terminus of railways from Anatolia. It was built between 1906 and 1908 by German architects Otto Rittner and Helmuth Cuno as a link in the Berlin–Baghdad railway. It represented an important stage in the incorporation of the Ottoman Empire into the economic system of Western powers. It then gained symbolic importance as the setting of arrival and departure scenes to Istanbul in literature and film. Yet, delinked from its physical context and history and juxtaposed with Taksim Square, it simply, and ironically, serves to “Ottomanize” (and by extension Islamicize) this modernist, secular Republican space. Another aspect about Haydarpaşa that ought to be mentioned is that the current government has been plotting to decommission and privatize the train station and the port area behind it for over a decade, despite protests and various forms of activism to protect it as a train station. Thus, when the 2010 ECOC Agency representative suggested that the ad image seeks to enable rediscovery, his words do not reflect the high level of anxiety the image may (and is perhaps intended to) provoke for individuals familiar with the politics of these places.

Figure 1.2 Original photograph used for the photomontage in Figure 1.1.

Photographer Azmi Dölen. İl Özel İdaresi.

Fast-forwarding three years, in 2013, the seemingly successful government of the AKP (Justice and Development Party, Turkish: Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi), in its third term, and political analysts were taken by surprise by the civil resistance focused on Gezi Park, abutting Taksim Square. The protests were triggered by the violent crackdown on peaceful demonstrators who sought to protect the park from demolition; the government’s architectural proposal, which would be allegedly implemented by a company owned by Erdoğan’s son-in-law, became the symbol of an increasingly authoritarian and corrupt government. The controversial project aims to privatize the public park to reconstruct in its place a mall resembling an Ottoman barrack that preceded the park—yet another attempt to rid Taksim Square and its surrounds of their representational symbolism as a Republican space of cultural modernization. The irony is that the former barracks were also a cultural modernization project of the late Ottoman state, and had replaced an Armenian cemetery.

Visual representations have power to shape the built environment. They can be read and used to support or critique particular projects in ways that may not have been intended by their original producers. The fictional images of the reconstructed Ottoman barracks used in news reports are a case in point. The images were lifted from an exhibition entitled “İstanbul’da Tarih ve Yıkım: Hayal-et Yapılar” (History and Demolition in Istanbul: Ghost Buildings, 2010), sponsored by the aforementioned ECoC Agency—this was an exhibition which had no intention of promoting the reconstruction of the barracks or, for that matter, any of the demolished buildings exhibited in the show.4 According to the preparatory archival exploration of the organizers, there had been earlier proposals in the 2000s to rebuild the barracks, but those proposals were shelved due to lack of support in the national assembly. The idea was revisited in 2011 and announced by Erdoğan as one of his election projects with an image from the exhibition.5 According to one of the architects who worked on the exhibition: “Since no one had any idea about the Taksim project, [Erdoğan and later news reports] used [their] image since it was already imagined.”6 The exhibition organizers were disappointed that their images were used without permission to visualize and therefore advocate Erdoğan and the AKP’s agenda; however, it was those same images that enabled different, agonistic, even antagonistic viewpoints to be articulated and framed the debate and informed the outcome of the built environment.

As a result of the protests, the reconstruction of the barracks was halted and the AKM gained new prominence in its abandoned state as the different groups participating in the protests used its plain, dark façade to hang posters and banners. The façade became a “speakers’ corner,” as it were. One directly addressed Erdoğan and defiantly said: “Shut up, Tayyip.” The violent police crackdown on the protests also involved cleaning that façade of the peoples’ messages and replacing them with a neatly arranged display of a giant portrait of the Republic’s founding leader, Mustafa Kemal, flanked by even bigger flags, temporarily restoring the building’s republican symbolism.

The protest for Gezi led to unprecedented unification, not only in response to police brutality but also because the controversy in question was the survival of a public park that could be physically occupied (when all other channels of communication failed), and, second, because there was a “tangible” architectural proposal. The AKP’s proposal for Gezi Park and the area around it, including the AKM and Taksim Square, became the focus of a lively debate, not only in Turkey but internationally. The previous decade was marked by a booming arts and cultural scene, the diversity and richness of cultural actors, newfound prosperity made visible in new consumption patterns under a neoliberal regime, and the open-mindedness of the government in supporting all this effervescence. As one analyst argued, the Gezi protests marked the “end of Cool Istanbul” (coined as such on the cover of Newsweek on August 28, 2005). Since then, Erdoğan’s belligerent response to public dissidence has only worsened.

The proposed replica of a long-gone Ottoman-era barrack, is a demonstration of Svetlana Boym’s suggestion, observed in relationship to Eastern European cities, that the future of the city is increasingly imagined based on improvisations on its past.7 The publicity image, with Haydarpaşa Train Station collaged into Taksim Square to replace the AKM, is a demonstration par excellence of the future of the city as a collage of pasts.

Open city

The term open city is an expression I came across in popular, mass-circulating dailies of the mid-1950s.8 It is a useful conceptual tool that allows me to tie seemingly separate phenomena—economic reforms, demographic growth, and changing urban form—to anxieties related to the city’s accelerating transformation. Originally used in conventions of war in Europe from the seventeenth century onward, the term designated cities that chose to abandon all defensive efforts, allowing invaders to simply march in, in order to protect historic landmarks and civilians.9 In contemporary urban planning literature, the term is sometimes invoked to describe a lack of growth controls that might otherwise be used to divert unwanted migrants. As such, “open city” represents an ideal on the opposite side of what Richard Sennett calls the “brittle city”—a closed, over-determined system that denies chance encounters, narrative possibilities, and growth over time.10 Recently, the term open city has acquired new cachet, prompting architects to consider whether design can be utilized to achieve this political ideal—to explore how “designing coexistence” might be possible.11 This new interest has been coupled with a return to Henri Lefebvre’s conceptualization of the right to the city and the broader movement of urban activism.

Theoretical reflections on the open city have so far focused on how the city can manage cultural complexity and the role manipulations of space and architecture might play in furthering this ideal. Defining the open city as one where “immigration is accepted by the people and the urban politics,” Detlev Ipsen remarks: “th...