Research in business-to-business marketing

Companies can achieve success and customer retention not only through the provision of good products but also by offering effective services and developing good relationships with supply chain members. Many business-to-business (B2B) managers believe that their customers act rationally and base decisions mostly on price; customer loyalty is not a consideration. However, achieving loyalty in B2B markets is difficult and poses unique challenges. It often involves complicated distribution channel structures – frequently having to navigate a significant gap between demand and supply, and manage large accounts with many people who influence the relationship. To add complexity but also opportunities to the issue, digitalisation of the business world provides new ways to keep in touch with customers (Lingqvist, Plotkin and Stanley, 2015). Most managers fail to recognise that the same customers who require a value proposition for purchases also require a different set of attributes for other products for which they will be prepared to pay more. Defining what the customers want and how best to engage them requires tailored solutions and a higher level of analysis across the supply chain. Customer loyalty in the B2B context is much more complex than is often reported (Hines, 2014).

A recent Bain & Company survey of executive-level managers in B2B industries throughout 11 countries shows that 68% of respondents believe customers are less loyal than they used to be. Moreover, the same survey reveals that earning loyalty in B2B markets faces unique business problems, often involving complex channel structures, concentrated buyer communities or large accounts, and continuous shifting of perceived value (Michels and Dullweber, 2014). Not all executives treat customer loyalty as something different from customer satisfaction. Customer satisfaction is just an attitude at a moment in time, while loyalty is actual behaviour that results in multiple buying cycles over time.

The term B2B indicates, firstly, all the relationships that a company has with its suppliers for procurement activities, planning and monitoring of production or support in product development activities. Moreover, it also describes the relationships that the company has with professional clients or other companies that are connected at different points of the production chain. A B2B relationship usually involves more than two or three individuals; all these people have different needs and backgrounds. The principle behind ‘relationship marketing’ is that the organisation should consciously strive to develop marketing strategies to maintain and strengthen customer loyalty (Reichheld, 1994). Conceptualising and analysing these marketing situations requires different research approaches that deal with purchasing complexity and customer prospect heterogeneity. In sum, it is a complex and heterogeneous business context. Second, in a B2B market, work experiences, production and engineering are essentials. Thus, companies that have a technical background but no business experience are less useful in professional development processes. Third, in a B2B context there is generally a lack of data availability; data for B2B contexts are rarer and more difficult to collect for scholars than are data for business-to-consumer (B2C) contexts. Thus, the domain of B2B research encompasses many open questions. Studying the B2B market could be useful for building theories related to different disciplines, but B2B research also faces heterogeneity in the units of analyses and thus can reveal different theoretical perspectives (Håkansson and Snehota, 1989; Reid and Plank, 2000; Gummesson and Polese, 2009; Vargo and Lusch, 2011). Early marketing was simply an application of economic theory, while business relationships were a combination of economic, organisational and social factors. Concepts like reciprocity, mutuality and trust have since acquired a new importance and they are closely connected to B2B research.

This view is clearly in contrast with the guidelines of economic theory, which focuses on the lowest production costs and maximum profits in the exchange. Economic theory researchers were primarily concerned with consumer markets, and the main goal was to connect consumers to society using, to begin with, economic theory, then later, social theory, and then organisational behaviour theory (Alderson and Cox, 1948; Alderson, 1965). Later, the line of reasoning changed slowly following the idea that customers are also important and could contribute to the creation of value. It was not until some years later that the first course in industrial marketing was developed at Harvard Business School by Ray Corey, who published Industrial Marketing: Cases and Concepts (Corey, 1962). Later Peter Drucker argued:

What the customer thinks he or she is buying, what he or she considers value, is decisive – it determines what a business is, what it produces, and whether it will prosper … Customers are the foundation of a business and keep it in existence. To supply the wants and needs of a customer, society entrusts wealth-producing resources to the business enterprise.

(1974 p. 57)

A notable contribution to research came from The Industrial Marketing and Purchasing Group, which was formed in the 1970s between five European research groups from France, Germany, Italy, Sweden and the UK. The approach was basically to see B2B marketing as an ongoing interaction between buyers and sellers; this approach is based on relationship marketing and implies the buyers and sellers are dependent on each other and create value for both sides (Håkansson and Snehota, 1989; Snehota and Håkansson, 1995; Gadde, Håkansson and Persson, 2010; Cantù, Corsaro, Fiocca and Tunisini, 2013). Then, in the 1980s, many marketers moved from the term ‘industrial’ goods marketing to ‘business’ marketing and, finally, by the 1990s, ‘business marketing’ frequently displaced ‘industrial marketing’ and the label ‘B2B marketing’ became very popular (Hunt, 2013). In recent years, B2B marketing has become a decision-making activity directed at satisfying customers’ needs and wants. Gradually moving towards B2B markets, it also required an analytical understanding of all members involved in the value chain.

Compared with B2C, B2B marketers focus on fewer and more varied customers, using more complex and typically oriented sales processes. The presence of a few powerful customers means that many common tools and data used in B2C are inappropriate for the B2B market. In addition, B2C transactions still occur through common channels; this is in opposition to B2B transactions, which are more private and direct. Thus, the key distinguishing feature of B2B is that the customer is an organisation rather than an individual customer, in contrast to consumer markets, which focus only on the relationship between the supplier and the final customer.

In sum, consumers, after all, care deeply about brands and are more readily influenced by advertising, media messages, special deals, coupons and word of mouth (WOM) through online or offline avenues, and they can switch from one brand to the next with little cost. Meanwhile, business purchase managers and supply managers conduct significant research, examine specifications, follow a formal buying or procurement process, experience high switching costs, and usually worry most about functionality, volumes and price (Lingqvist et al., 2015). Finally, in the B2B context, decision-makers buy with the ultimate goal of adding value at less cost to move the products from upstream of the value chain to downstream.

Supply chain management: a pillar for business-to-business marketing

Alderson and Martin (1965) stated that the key to maximising organisational wealth was to integrate the diffused transactional and transvectional demand and supply elements in the distribution channel to create value. A transvection is, in a sense, the outcome of a series of transactions beginning with raw materials and ending with a product at the consumer level. Alderson’s transvection (1965) presages what is now referred to as ‘supply chain management’ (SCM), incorporating the theory of marketing (Hunt, 2013). According to Esper, Ellinger, Stank, Flint and Moon (2010), Alderson demonstrates how the flow of information and product alteration or transformation results in transvections, or an entire system of exchanges that are premises of the need of demand and supply management integration. Indeed, over the last 20 years there has been a significant directional change in both marketing practice and theory with regards to the idea of relationship marketing – that is, establishing, developing and maintaining successful relational exchanges (Morgan and Hunt, 1994). Today, the relevance of relationships between customers and suppliers is extensively recognised in the business literature.

Interest in the supply chain concept has received considerable attention since the 1980s, especially since firms have realised that the market’s evolution towards a reduction in lead time and more responsive supply would drive them into organisation isolation from the other members of the chain. SCM thus plays a key role in exploring such relationships across the supply chain.

However, even with great interest in the topic, there is no definitional consensus for SCM among scholars and practitioners. We view the supply chain as:

The systemic, strategic coordination of the traditional business functions and the tactics across these business functions within a particular company and across businesses within the supply chain, for the purposes of improving the long-term performance of the individual companies and the supply chain as a whole.

(Mentzer et al., 2001, p. 11)

The main idea is to consider supply chain as a flow in which the members have only the function to choose the physical flow of goods. New research and theories in addition to those concerning the typical members of a supply chain have considered other members who have a supportive and secondary role but who are equally important.

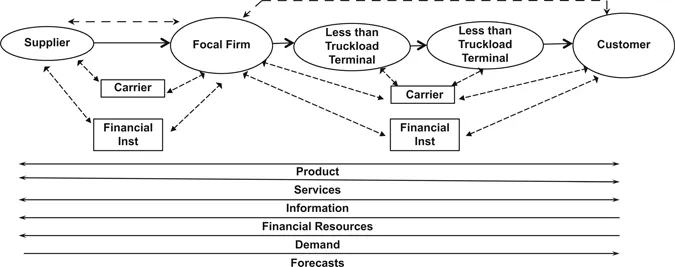

A relevant contribution comes from the network perspective used by Carter, Rogers and Choi (2015), which defines the supply chain as a set of nodes and links. A node represents a member of the chain with the ability to maximise its own profit while respecting the limits in which it operates. A link consists of the transactions between two nodes. Thus, the supply chain is a complex and dynamic system that is difficult to forecast and control. Each node in the supply chain manages its own resources to obtain a profit and coordinates its actions with the purpose of achieving visibility upstream towards its suppliers and downstream to its customers. However, as we have seen, other members can influence the performance of a specific node; beyond their visibility range, an agent is subject to the decisions of the other members and cannot exercise control over them. For every supply chain, the mechanism is the same: to analyse a single situation, we must refer to the focal company. The case of an individual agent and of the focal firm can differ from one another based on the typology of goods or the mode of transportation. However, the specific case is important to identify in order to analyse a supply chain and a point of reference. Each agent can be involved in a unique supply chain or in many. While Mentzer et al. (2001) analyse the complexity of supply chains, identifying numerous actors with increasing complexity, Carter et al. (2015), concentrate more on the nodes and links of the supply chain, where customers and suppliers often connected not as a linear chain but as a network. In particular, the model shown in Figure 1.1 illustrates the dynamics of carrier activity. The carrier is considered as either a physical or a support node, demonstrating a more complete framework of how value-adding activities are organised in a supply chain. In that case a product moves from the focal agent (node) through warehouse terminals to the focal agent’s customer in the physical supply chain.

Figure 1.1 The physical and support supply chain as a network

SCM coordinates business functions within and between organisations and their channel partners. SCM strives to provide goods and services that fulfil customer demand responsively, efficiently and sustainably. Further, it includes functions such as demand forecasting, purchasing or call sourcing, customer relationship management and logistics. Thus, supply chain perspectives reflect knowledge and operational capabilities through information coordination and collaboration across organisations throughout the service ecosystem. When supply chains are not integrated in the product, information and financial flow, or are not appropriately organised and managed, the results are inefficient and resources are wasted.

Thus, over recent years the increased interest in SCM can be summarised as:

- increasing consumer expectations of product quality and customer service coupled with local and regional preferences across multiple marketing channels;

- increased globalisation, which has created a geographical decomposition of the value chain, with the most common phenomena being global sourcing and offshoring;

- great environmental uncertainty resulting from the huge impact of technology and digitalisation, competition, different governmental rules and regulations, macro-economics, world geopolitical dynamics and rising levels of material scarcity for raw materials; and

- the trend towards reducing lead time and increasing services, which require closer relationships and coordination between the members of the supply chain, mainly in the era of e-commerce.

These dynamics will affect the efficiency (i.e., cost reduction) and the effectiveness (i.e., customer service) of supply chains designed to create time, place and form utility to improve the customers’ commitment.

Additionally, we are in an era of global supply chains comprising a worldwide network of suppliers, manufacturers, warehouses, distribution centres and retailers through which raw materials are acquired, transformed and delivered to customers. Moreover, changing demographics, with middle-class growth in China, India and Vietnam, and expectations of higher growth for some countries in Africa, have led global companies to mine these new markets for growth and profitability. Nowadays 54% of the worldwide population lived in an urban area, which is expected to rise to over 66% by mid-century (United Nations, 2015); this will be a challenge for companies and third party logistics due to an increase in online shopping will require more urban logistics premises to fulfil late cut-off deliveries.

Today, supply chain managers must develop competencies that allow them to understand complexity, anticipate major changes and trends and adapt to those changes as needed.

Consequently, such a context leads companies in one country to depend on companies from other countries, either to supply material or to market their products. This strategy also renders organisations potentially less responsive, more dependent on long-term forecasts and vulnerable to the delay and change of demand. Globalisation has set up large systems of trading partners that span vast distances. Vertical integration, once commonplace, is now rare. While outsourcing has cost advantages, it also has a downside – lack of control and oversight; globalising the marketplace and the need of logistics service providers to render logistics services on an international scale requires i...