![]()

Section 1

Re-Presentations of Difficult Histories

![]()

1 Sustainable History Lessons for Post-Conflict Society

Sirkka Ahonen

History as a Moral Craft

“History,” in the broad sense of the term, comprises different representations of the past, ranging from vernacular memories to public monuments, museums, commemoration rituals, historical fiction and school history. The representations are socially produced and reproduced, and are dependent on time, space and social context. As a social asset, history has a moral dimension.

The Swedish author Mikael Niemi in his autobiographical novel Popular Music (2003), tells of being expected to identify with family claims of historical justice. The family lived in a small village in the periphery of Sweden. In the early 1960s, when the son became of age, the father obliged him not to forget the past:

There are two families in this district that have caused us a lot of harm, and you are going to have to hate them for ever and a day. In one case it all goes back to a perjury suit in 1929, and the other it’s got to do with some grazing rights that a neighbour cheated your grandad’s father out of in 1902, and both these injustices have to be avenged at all costs, whenever you get the chance, and you must keep going until them bastards have confessed and paid, and also gone down on their bare knees to beg forgiveness.

(p. 263)

Niemi’s experience illustrates ubiquitous historical moral burdens of communities, including nations. History as such does not cause armed conflicts, but, nevertheless, it has the potential to turn performative and trigger social and political antagonisms. Lack of mutual recognition of the cherished narratives of the past may raise political separatism, and ancient hatreds may be used as rhetorical tools to incite aggression.

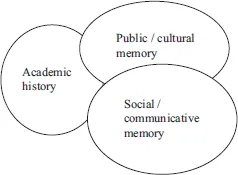

History provides a community with a historical identity. Identification with the community depends on an experience of continuity. Without such experience individuals would assume volatile roles rather than stable identities. The identity of a community is socially constructed. Members of the community mediate memories and accommodate them to changing life situations. Memories are not created in a sealed vacuum but through a social process. What no longer can be reached by live storytellers will be mediated by public memory, that is, official memorializations of the past and commercial or civic cultural products with historical content, and, not least, by history education. Jan Assmann (1995) calls public memory “cultural memory” and regards it as the necessary complement to orally mediated “communicative memory.” Owing to cultural memory, modern people, too busy to tell each other antiquated stories, get into touch with history.

Communicative and cultural memory—in other words, social and public memory—constitute the two widest fields of producing history, that is, representations of the past. Nevertheless, traditional academic history has a role to play in the broad social realm of history. Scholars with professional critical skills know how to deconstruct myths and open alternative perspectives to past events. At the same time they still align with vernacular historians in the quest for answers to socially relevant questions about the past. Academic historical research is an essential but narrow field of history production. The three fields—that is, social memory, public memory and academic history—interact and together contribute to the everlasting meaning-attribution to the past (see Figure 1.1).

The most common form of communicatively and culturally constructed memory—in other words, social and public memory—is narrative. Narrative forms of knowledge are fostered in both social and public memory to make sense of the past. A narrative melds the loose items remembered or retrieved from the past by people into a coherent story with a beginning, a main body and an end. A narrative has a plot, and the plot makes the past comprehensible by attributing meaning to it.1

A narrative is constructed by attributing meaning to facts. This meaningfulness is both a strength and a weakness of narratives. A narrative makes the past look like a coherent line of events and, moreover, suggests a course towards the future. The weakness of the narrative is constituted by the subjectivity of the meaning attribution. According to the Dutch philosopher of history Frank Ankersmit (2001), the subjectivity of narratives categorically separates them from objective facts. He distinguishes “referential statements” and “narrative substances.” The former refers objectively to evidence and obeys the disciplinary rules of source criticism, and can be called “facts,” while the latter, attributing meaning to a narrative, depends on the subjective perspective of the author. Narrativity gives substance to history and thus makes it socially relevant but at the same time subject to a change of perspective. History is inevitably a process, wherein the meaning of the narratives is negotiated over and over again (Ankersmit, 2001, pp. 237–239).

Figure 1.1 Fields of making history

Narratives tend to be socially exclusive, as the perspective of an individual narrator depends on his or her social context. Exclusiveness makes narratives socially unsustainable. In the quotation from Niemi that opens this chapter, the author discloses the frustration of social underdogs who in the mainstream narrative of the time period were not recognized as actors of history. The problem of exclusivity was accentuated in the 20th century nation-states, as a nation-state with sanctioned political borders inevitably implies the construction of minorities as well as irredenta areas and expatriate communities across the border.

Socially constructed narratives tend to include and mediate moral claims. Moral standpoints reinforce the plot of a narrative by providing it with a contrast between good and bad actors. Niemi (2003) shows how ancient hatreds in a small rural village are mediated by family narratives. Even if disputes of territorial rights had been dealt with in court, a moral grudge would have been transferred to successive generations. Intercommunal and transgenerational moral claims are the core issue of historical justice. Using Australia as an example, the philosopher of justice and law Janna Thompson (2002) in Taking Responsibility for the Past argues that historical responsibility is transgenerational. As long as an institutional continuity rules in a state, the moral responsibility transcends generations (pp. XVIII, 36). For example, the institutional continuity prevailed despite Australia changing from a British colony to an independent federal state. Therefore, the quest for historical justice as it appears in the social memory of the aborigines continues to be politically recognized by the present generation. Thompson generalizes the Australian quest into a universal rule. She deplores that:

History is a tale of unrequited injustice. Treaties have been broken, communities wiped out, cultures plundered or destroyed, innocent people betrayed, slaughtered, enslaved, robbed and exploited, and no recompense has ever been made to victims or their descendants. Historical injustices cast a long shadow. Their effects can linger long after the perpetrators and their victims are dead. They haunt the memories of descendants, blight the history of peoples and poison relations between communities.

(pp. VIII, 8)

Because of their moral element, narratives have the potential to be performative. After a conflict, narratives of victimhood and guilt may mobilize people to an active search for reparation and retribution. However, the parties to the conflict customarily spin contradictory narratives; fostering them perpetuates conflict and hinders the reconstruction of society. The search for social cohesion and common bearings for future orientation is hard for a community because of conflicting narratives. Moreover, because of the performative potential, narratives may be deliberately used by politicians to incite enmities and aggression. The narratives of past victimhood and guilt are usable tools of political persuasion.

My comparative study of representations of a difficult past in public memory refers to the examples of Finland after the class war of 1918, South Africa after the armed racial conflict and apartheid of 1960–1994 and Bosnia-Herzegovina after the ethno-religious war of 1992–1995. I chose these examples partly on my familiarity with the countries and partly because the cases illuminate different kinds of conflict. Moreover, Finland provided an opportunity to study how time heals wounds (Ahonen, 2012).

Moral Myths Shaping Maintaining Historical Divisions

A moral narrative of the past is customarily based on the opposite positions of victims and perpetrators. The contrast bolsters the power of narratives. The most powerful narratives are reinforced by references to internationally travelling myths of victimhood and guilt. Such myths are often applications of biblical arch-myths, but some are retrieved from a more modern political repertoire.

George Schöpflin and Paul Kolstø, when seeking the most common moral arch-myths, characterize them as spin-offs of the biblical stories of the victimhood of Israeli people and the guilt of their old foe, the Philistines. The template of the myths consists of the victimhood of “us” and the guilt of “the other.” Schöpflin (1997) and Kolstø (2005) point out following arch-myths.

- Unjust treatment: A community fosters stories of deception and exploitation by “the other.”

- Old foe: A community presents “the other” as the historical aggressor against “us.”

- God-promised land: A community suggests having a divine right to a territory.

- God-elected people: A community legitimizes war and trusts the victory because of having God on its side.

- Redemption: Redemption after suffering may come as military victory, liberation or successful revolution.

- Rebirth and renewal: The dark past of a community can be deleted by a political conversion.

- David against Goliath: Military valor is used to justify the victor’s inalienable rights and denounce political compromises.

Among the arch-myths of more modern origin, the most prominent are genocide and holocaust, have travelled widely after the Second World War and induced many ethnic communities to claim victimhood. The Catholic Church fosters the historical myth of antemurale christianitatis, according to which an armed defense of the Church renders unto a community and its army a special moral worth.

According to my study of representations of guilt and victimhood in Finland, South Africa and Bosnia-Herzegovina, myths tend to be used reciprocally and symmetrically by the adversaries.2 In the Finnish case the adversaries were constituted by the socialist Reds and bourgeois Whites, in Africa by the Black Africans and White Afrikaners, in Bosnia-Herzegovina by Orthodox Serbs, Catholic Croats and Islamic Muslims.

In Finland (see Table 1.1) both the Reds and the Whites referred to an “old foe”: for the Reds it was constituted of the landowning class; for the Whites it was the Russians. Both Reds and Whites accused each other of atrocities comparable to those the Philistines committed against the Israelis in the Old Testament. The Whites trusted in earning redemption as “God-elected people” while the Reds looked forward to the fulfillment of the promise of revolution.

In South Africa (see Table 1.2), both the Africans and the Afrikaners regarded themselves as victims of unjust treatment in the past. The Afrikaner victimhood story referred to the British cruelty in the Anglo-Boer War of 1899–1902. The Afrikaners considered the establishment of the apartheid regime in 1948 to be the divine redemption of them as God-elected people. The Africans based their trust in redemption and the coming of majority rule on the myth of God-promised land and the Marxist promise of emancipation.

Table 1.1 Reciprocity of the myths bolstering guilt and victimization in Finland* (+ = the myth supported; − = the myth not supported) | | Reds | Whites |

| old foe | + | + |

| atrocities | + | + |

| redemption | + | + |

| God-elected people | − | + |

*See e.g., Manninen, 1982; Peltonen, 1996; Siltala, 2009; Roselius, 2010.

Table 1.2 Reciprocity of the myths bolstering guilt and victimhood in South Africa* (+ = the myth supported; − = the myth not supported) | | Africans | Afrikaners |

| unjust treatment | + | + |

| redemption | + | + |

| David and Goliath | + | + |

| promised land | + | + |

| God-elected people | − | + |

*See e.g., Coombes, 2003; Field, 2008.

In Bosnia-Herzegovina (see Table 1.3), each party claimed victimhood of equivalent atrocities. Both Serbs and Muslims regarded the ethnic cleansings of their towns as genocides. Croats appealed to the Vatican to have their war recognized as antemurale christianitatis, which would entitle their community to a reward of territorial expansion. All parties expected an ethnically defined nation-state as redemption.

By pointing out the reciprocity of the attributions of guilt and victimhood between conflicting communities, I do not mean to disqualify and relativize their idiosyncratic narratives. The narratives correspond to the experiences of the communities. In Bosnia-Herzegovina, when the Muslim textbook writers in 2008 were urged by the Council of Europe experts to assume a multiperspectival look at the sufferings of the war 1992–1995, an unnamed leader in the local newspaper exclaimed: “Do you want us to tell lies to our children?!” (Vecernje Novine, 2008). In an interview-based survey by the international Open Society Fund at the same time, more than half of parents and students, however, regarded the prevailing history lessons to be ethnically biased (Education in Bosnia-Herzegovina: What do we teach our children? 2007, pp. 51–52, 58–59).

Neither do I urge a straightforward scholarly deconstruction of the mythically loaded identity narratives. History is vital for human beings in their life-orientation, and grand narratives are a source of constructive membership of a community. To come from outside, like the international experts of history education in Bosnia-Herzegovina, and ask history teachers to dedicate their classrooms to source criticism and multiperspectival accounts, would deprive history of the important function of identity building. Nevertheless, as socially exclusive narratives constitute a risk to mutual understanding in a divided community, an interaction between the narratives is a necessity—especially as it is in line with the nature of historical knowledge: The picture of the past is never complete if looked at from one angle solely.

Table 1.3 Reciprocity of the myths bolstering guilt a...