The UGTT has a unique organizational structure in relation to other Arab or French unions, leading some observers to speak of “two UGTTs” or to define the UGTT in terms of its structural and/or political ambivalence (Chouikha and Geisser, 2010; Gobe, 2008), while others see a reflection of the incomplete modernization of Tunisian society (Hamzaoui, 2013; Amami, 2008). However, a static or binary perspective that postulates direct competition—reified at its core between a bureaucracy guided by impersonal rules designed to uphold “modernity” and local social practices that must be overcome—does not suffice to fully explain that unique structure that emerged from the colonial trade union tradition. The primary aim of this chapter is to retrace the history of the Tunisian trade-union movement and its impact on the development of the UGTT. The chapter will follow the advance of the national union movement—framed in its proper economic, social, political and cultural context—taking into account the historical processes and prevarications among Tunisian social movements at the root of the negotiations that imposed the colonial union model, which led to the emergence of a uniquely Tunisian union organization. I will then endeavor to describe the mechanisms that govern relationships within the UGTT and the union’s unique position in Tunisian politics, as explained by the UGTT’s past relations with the single-party state, which were characterized by compromises as well as dissidence expressed via confrontation and avoidance strategies.

The Emergence of the Tunisian Labor Movement

The Tunisian labor movement took root at the start of the 20th century. The movement continued to develop in reaction to capitalist colonial exploitation and the arrival of foreign workers and union organizations that predated the formation of the Tunisian working class. How did the union movement born in Europe, which arrived in Tunisia along with colonial capitalism, affect local labor conditions? How did the working class interact with the national independence movement? How did social and political struggles play out in the battle waged by the Tunisian working class? What alliances did Tunisian workers form to break free from French dominance and join the fight for independence? The answers to these questions do much to explain the UGTT’s current structure and role in Tunisian politics.

The spread of French colonial capitalism greatly intensified following World War I, permeating all economic sectors, from agriculture to mining and infrastructure. This growth was reliant on imported labor from Europe (France, Italy and Malta) for skilled positions and from North Africa (Libya, Algeria and Morocco) for low-skilled and unskilled infrastructure and mining jobs (Yousfi, 1983). Union work was initially reserved for Europeans, who were in the majority in all working-class sectors, including mining, construction, transportation and the food industry. As Tunisian craftsmen and farmers’ (fellahs) situation grew increasingly unstable, Tunisian workers gradually began to take jobs at colonial companies. They joined French union confederations such as the CGT5 and CGTU,6 which provided an organizational model and a place to become acquainted with union culture, but also perpetuated their marginalization and discrimination. Tunisian workers were underpaid in relation to the Europeans and especially the French, who benefitted from the “colonial third”—a 33% wage premium (Bessis, 1974). Tunisian workers quickly realized that the French unions were failing to defend them adequately and that they were mainly used as a bargaining chip to win concessions for French employees, compelling the Tunisians to create their own independent union.

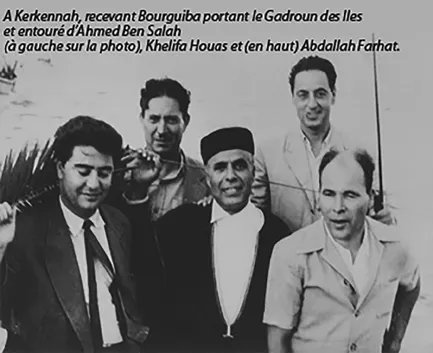

The first independent Tunisian union organization, the General Confederation of Tunisian Workers (Confédération générale des travailleurs tunisiens, or CGTT), was established by Mohamed Ali Hammi on December 3, 1924, four years after the birth of Destour7 and the Tunisian Communist Party (PCT). Authorities from the French protectorate moved swiftly to suppress the CGTT and, after a series of labor strikes and protests, arrested Mohamed Ali Hammi and his comrades. In 1937, Belgacem Gnaoui founded the second incarnation of the CGTT, but conflicts between the union and the Neo-Destour Party8 enabled the colonial authorities to curb the national movement and nip this second attempt at unionism in the bud. The third initiative was initiated by transportation-sector employee Farhat Hached, who created the UGTT with other Tunisian unionists on January 20, 1946, following a split with the French CGT. The UGTT launched a two-pronged campaign for workers’ rights and national independence, forming an alliance with Neo-Destour. When the political party’s leader, Habib Bourguiba, was arrested in January 1952, union chief Hached took charge of the national liberation movement. Hached would lead the movement until December 5, 1952, when he was assassinated by colonialist far-right elements abetted by the French secret service.

Two fundamental characteristics emerged from the origins and development of Tunisian unionism that would greatly affect the structure of the UGTT and the role it plays in Tunisian politics.

First, the Tunisian economy comprised two superimposed structures during the colonial era: a capitalist structure prevalent in industry, which was dominated by the French, and a structure with traditional relations of production that had long governed the peasantry and handicrafts (Ben Hamida, 2003). Thus, capitalist employer-employee relations based on salaried work became intertwined with pre-capitalist social relations organized by local communities. This model gave rise to a highly diversified proletariat. Ethnic and professional diversity became enmeshed with local, regional and tribal forms of solidarity that had a considerable influence on how the union confederations took shape. This unorthodox path to economic development was chronicled in several colonial works that stigmatized Tunisian workers, who were depicted as lacking balance or, at best, lagging behind western workers. One such example can be found in the memoir written by Louis Morel, Civil Inspector9 for the Gafsa region, on the Gafsa miners (1949) (quoted in Amami, op. cit., 77):

In this case, the major error would consist, for example, in believing that the working masses standing before the trade union are similar or at least comparable to its followers in western countries. The union has to contend with the tribe, a group that is older, more homogenous and sturdier than itself. It even has to pursue a policy of selecting leaders based on their local stature. The end conclusion is that there is a clear gap between the Gafsa miners’ technique, in the broadest sense of the term, and their customs, which lag several centuries behind.

(Morel, 1949, 225–7)

For his part, Max Pellé (quoted in Amami, op. cit.) expressed amazement at the persistence of a form of dualism among Tunisian workers, which reminded him of laborers from the early 19th century. In a letter to the minister of foreign affairs dated November 6, 1907, Pellé wrote:

The union movement is confronted with groups of workers who experience a sort of dualism with regard to their conscience and sense of belonging. On the one hand, they belong to a community of workers who share the same interests; on the other hand, they belong to a national or ethnic tribal community. And while work at large capitalist and colonial companies fosters communication with other communities and brings them closer together, because they share the same working conditions, each day after work the workers return to their neighborhood, family, tribe or ethnic or national community—a world that is almost completely closed off.10

The union movement worked to build a sense of unity among workers in specific trades and sectors in order to overcome these community, tribal and ethnic divisions. However, colonial companies treated Tunisian workers in such a way that it was difficult for them to identify solely as working class. Viewed from this perspective, the classic theory that “archaic” relations stifled the emergence of “modern” social relations (Tabbabi, 2006) appears less valid. The colonial ethnic hierarchy was more responsible for Tunisian workers’ refusal to trade their tribal/community support system for pseudo-working-class unity that did not afford them any form of protection. French business owners exploited these community ties extensively as a means of eroding workers’ unity, but these clans also served as a resource that helped Tunisian workers withstand the alienation caused by the colonial capitalist system. This type of solidarity played a formative role, as demonstrated by the presence of individuals from the same region or even the same town in the leadership of the first independent union organizations. Each new trade union provided an opportunity for members to formalize new regional and sector-based ties.11 The first independent unions were created by groups on the fringes of urban society—the most impoverished subset of the emerging working class. Notably, migrants from the South working as dockworkers in the port of Tunis were the first to hold a wildcat strike, in August 1924, causing the split with the local section of the General Confederation of Labor (CGT) that led to the creation of the CGTT. Kerkennah Islands natives in Sfax would go on to form the core independent unions in the South, which helped bring about the founding of the UGTT in 1946 (Ben Hamida, 2001). The Gafsa mines offer a good example of the extent to which geography and community influence union practices (Hermassi, 1966). The workers and union leaders’ shared geographic and social origins strengthened cohesiveness as the workers’ movement continued to spread.

Thus, the Tunisian union movement, a product of colonialism and an ethnically diverse working class, comprised communities of workers with multiple allegiances—to workers’ groups that share the same interests and to tribal, regional and national groups—whose propensity to take action varies in relation to the political and social climate. This vacillation between the imperative for workers’ unity and community/ethnic priorities shaped the birth and development of the Tunisian union movement. The system in place at the UGTT would come to reflect this history, once strictly formal union relations could be paired with other political, regional and local affiliations that extended beyond the scope of the organization. This array of communities was matched in diversity by the social backgrounds of UGTT members. Highly qualified workers were joined by others who had only recently entered the ranks of the working class, many of whom small-scale farmers, craftsmen and shopkeepers. Teachers, office workers and public-sector officials rapidly became central to the union, particularly in supervisory roles. Traditional hierarchical relations, social differences and regional and professional diversity combined to form a unique bureaucratic apparatus and organizational culture (Khiari, 2003).

Second, tensions gradually rose in the Tunisian labor movement between economic and political initiatives. The union movement was torn between focusing mainly on economic issues and remaining a minor player in the struggle for independence, or becoming “nationalistic” and abandoning the class struggle. On the one hand, the social struggles enlisted Tunisian workers in a form of class warfare that spurred them to join forces with European workers in order to gain leverage over employers, which pushed national independence into the background. On the other hand, the political struggle for national independence required Tunisian workers to cut ties with the existing European union movement, which paid little regard to the national anti-colonial aims of the Tunisian working class.

The contradictions in the universalistic language employed by the CGT illustrate this point. At times, the CGT would excoriate colonial policy, but the union also often proclaimed the French presence in Tunisia as an opportunity to “civilize the Tunisians” and transition from “feudal” relations to “modern” relations. Moreover, the CGT’s defense of equal work for equal pay was far from sincere, given the disparity in wages for workers of different nationalities. The fact that Tunisian workers suffered from both social and political oppression gave substantial impetus to the independent union movement, whose main goal was to merge the struggles for social rights and independence in trade union action (Yousfi, op. city.; Bessis, op. cit.).

Meanwhile, the national liberation movement suffered a long series of leadership crises. The nationalists (Destourians) and communists fought violently for ideological and political control over the movement. The Franco-Tunisian Agreement signed in 1954 specified that France would retain authority over Tunisia’s domestic and external security for ten years, opening a deep rift within Neo-Destour between the two leaders of the liberation movement, Salah Ben Youssef12 and Habib Bourguiba. Unlike Bourguiba, who advocated negotiating “phased-in” independence and making compromises with France, Ben Youssef supported Pan-Arabism, gave pride of place to Islam and wanted full independence immediately (Bessis and Belhassen, 2012). The conflict provoked violence and divided both their supporters and the country as a whole. Within the UGTT, the upper-class nationalist elite that belonged to Neo-Destour and the working class, who mainly came from disadvantaged areas, had a complicated relationship. In the end, the UGTT, including a number of Destourians, joined the liberation campaign led by Bourguiba and played an active role in the fight for independence.

The Neo-Destour Party Congress, held in Sfax from November 15 to 19, 1955, was a momentous event that cemented the UGTT’s place in the struggle for independence and set the stage for the union’s future relationship with the single-party state. The congre...