![]()

1

Lucania and Lucanians

οἱ δὲ Λευκανοὶ τὸ μὲν γένος εἰσὶ Σαυνῖται

(Strabo 6.1.3 C 254)

The mountainous nature of ancient Lucania is the leitmotiv in both ancient and more recent descriptions of this area of southern Italy. In his account of the historical events involving Lucania, Livy makes a few references to the harsh landscape of this region.1 Cassiodorus refers to mountuosa Lucania,2 and still in the 1500s the region was similarly defined montuosa et horrida by G.A. Magini.3 Several rivers cross the Lucanian territory, thus creating a natural connection between its internal part and the coasts, where the Italiote cities were located. It is in this mountainous landscape rich in water streams that the Lucanians settled and shaped their territory according to their needs and their political and institutional arrangements.

This chapter provides a description of the physical geography of ancient Lucania and discusses the debated historical phenomenon of the appearance of the Lucanian ethnos in the scenario of Magna Graecia toward the end of the fifth century BC. Furthermore, both the political and the territorial organization of the Lucanians are illustrated in order to better contextualize the role played by cult places in the social, political, and cultural reality of ancient Lucania.

1.1 Lucanian borders and geographical setting

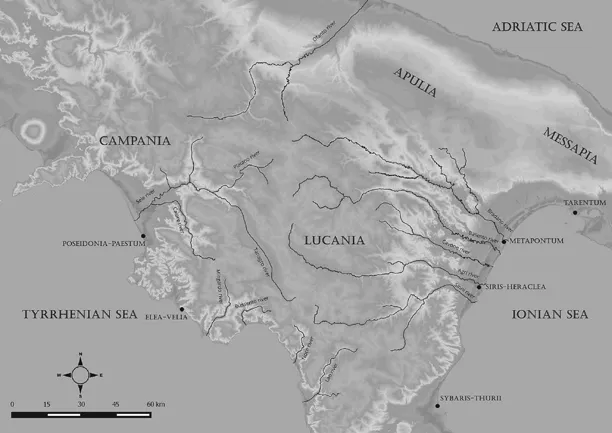

The area known in ancient sources as “Lucania” grosso modo corresponds to modern southern Campania, Basilicata,4 and northern Calabria (Figure 1.1).

High mountains dominate the middle-northern part of the region, while steeply sloping hills mark the southern part overlooking the Ionian Sea. The central area is almost completely mountainous and is characterized by numerous river valleys. In a territory that is mainly mountainous and that has a limited number of flat areas, it is no surprise that the hydrographic basins constituted a vital component for the life of the ancient communities: the waterways, in fact, were the most important communication routes, connecting the coasts with the hinterland. The river system thus strongly influenced the settlement pattern of

Figure 1.1 Ancient Lucania. Geographical features and location of the Greek colonies

Lucania from at least the eighth century BC, when the main indigenous settlements were set up on high-ground areas, which geographically overlooked the natural routes marked by rivers.5 On the western side of the region, the Marmo, Platano, and Melandro streams flow into the Tanagro River; on the southwest side, the Noce River flows directly into the Tyrrhenian Sea; on the Ionian side, the five major rivers of the region – Bradano, Basento (Casuentus), Cavone, Agri (Akiris), and Sinni (Siris)6 – flow into the Ionian Sea, thus representing a natural link between the Ionian coast and the mountainous heart of Lucania.7 Finally, the wide river valleys of the tributaries, such as Sauro and Sarmento, created a network of communication routes within a short distance.

Lucania is bordered by the Ionian Sea on the southern side, where the Greek colonies of Metapontum and Heraclea are located, and by the Tyrrhenian Sea on the western side, where the Greek cities of Elea and Poseidonia are. The Tyrrhenian coast reaches from the mouth of the Silaros River as far as the mouth of the Laos River, comprising the entire modern Cilento peninsula. Such a coast appeared much longer in antiquity, as well as high and rocky, with a number of narrow inlets that were appropriate for use as temporary ports. Instead, the Ionian shore was flat and sandy; the coast had a linear profile, without any natural inlet. The alluvial supplies of the five rivers that cross the Ionian coast make it marshy.8 Moreover, the lack of docks in antiquity, which is also documented by Strabo,9 makes the ancient coast similar to its modern profile.

In addition to these rivers, Lucania is also dotted by a number of lakes that are located either on the top of mountains (such as on the close-by mountains of Calabria) or on plain valleys (such as the Monticchio and Pignola lakes).10 As documented by geomorphological studies, some of the valleys of the region had originally been large water basins, which, towards the end of the second millennium, were transformed into lands to be cultivated. Finally, Lucania is rich in spring water, and it is in proximity to springs that most of the Lucanian cult places were built during the fourth century BC.11

Despite these geographical and climatic features, the Ionian area has environmental characteristics that make it particularly suitable to human settlement and agriculture, including the presence of the rivers that link the coast with the internal part of ancient Lucania.12

Before the new territorial and administrative organization set up by Augustus, which incorporated the territories of Lucania and Bruttium into the Regio III,13 the limits of the Lucanian area tended to be ambiguous and ephemeral, and they likely did not reflect the ethnic cohesion that is commonly attributed to them by written sources. According to Strabo, who provides us with the most detailed geographical description of ancient Lucania,14 the Silaros River, on the northwestern side, and the Bradano River, on the eastern side, constituted the extremities of the region.15 The Augustan reorganization of the peninsula into regiones kept the Silaros River as the southern border of Lucania, separating Regio I (southern Campania) and Regio II (Apulia et Hirpinia) from Regio III (Lucania et Bruttium).16

The northeastern part of Lucania is somewhat problematic to define from an archaeological perspective: the area of Melfi (including the sites of Banzi and Lavello), located between the Ofanto Valley and the northern segment of the Bradano River, tended to have cultural features that were congruent with those found within Daunia rather than with Lucania,17 thus demonstrating the extreme fluidity of the concept of border in pre-Roman Italy.18 For this reason, the area of Melfi will be excluded from this current work on Lucanian cult places.

1.2 The emergence of the Lucanian ethnos

The ancient name of the historical region described by Strabo derives from the population known in literary and epigraphic texts as “Lucanians,” who appeared in the historical scenario of Magna Graecia between the end of the fifth century BC and the beginning of the following century.19 Before the emergence of this ethnic entity, the area that was later named “Lucania” was inhabited by indigenous populations, which – in the Greek and Roman traditions – were identified as Oenotrians and Chones.20

During the late fifth century BC, the area experienced a structural change, which is documented in both written and archaeological sources: the transition from Οἰνωτρία to Λευκανία. This transformation was certainly evident to ancient people, as attested by literary tradition and in particular by Strabo, who mentions a succession of Oenotrians-Chones, Greeks, and Lucanians in the Lucanian region.21

It is only from the fourth century BC that written sources start mentioning the Lucanians22 (who were later referred to as Leukanoí and Brettioí), thus reflecting the need of distinguishing them as an autonomous ethnic entity, which was at that time setting up the territory and structuring its own political and social institutions. A crucial milestone in the process of formation of the name of the Lucanians is the Roman age, when the Lucanians started being involved in the hostilities with Rome. As Musti notices, Fabius Pictor (in Polybius 2.24) distinguishes between Lucanians and Samnites; conversely, in Timaeus (between the end of the fourth century BC and the beginning of the following century) such a distinction does not appear. Certainly, a real change in perceiving the Lucanians as an autonomous ethnic group occurred when it was possible to identify a geographical area definable as “Lucania.” This is reflected in the famous elogium of Scipio Barbatus that mentions omne Loucanam; this text describes events dating to 298 BC, although the inscription dates from the last decades of the third century BC.23

The Lucanians, along with other Italic24 peoples, were perceived not only as distinct from the Greeks and Romans but also as an ethnically separate entity within the Italic world.25 It had, in fact, unique characteristics that were different from those common to other indigenous populations of the Italian peninsula.26

The terminus post quem for the birth of ancient Lucania, corresponding to the region described by Strabo, must be fixed to 356 BC, when the Brettians (originally part of the Lucanian/Samnite ethnicity27) became an independent group with its own political organization.28 In addition to Strabo’s Lucania, in fact, ancient sources mention another Λευκανία, dating from a period preceding the Brettian schism. For instance, Ps. Scylax29 suggests that, between the end of the fifth century and the beginning of the fourth century BC, the Lucanians settled in a region that extended from the territory between the Silaros River and Laos on the Tyrrhenian coast, the Bradano and Coscile rivers on the Ionian coast, and the northern part of modern Calabria up to the Isthmus of Lametia. In particular, Strabo allows us to collocate the limit of the Lucanian area in the Isthmus of Scylletium and Hipponion, as he reports that Dionysus I of Syracuse intended to build a wall in that spot, in order to limit the Lucanians’ playing field.30 This area has been defined by Lepore as “grande Lucania”31 (Greater Lucania), a label that suggests its bigger size during the pre-Brettian era. According to written sources, it is in this Greater Lucania that the “capital” city of Petelia was located.32

About the origin of the Brettians, Strabo reports two different versions. In one passage, they are considered rebel shepherds who were subject to the Lucanians but later became independent.33 In another passage, Strabo says that the Brettians derived from the Lucanians, who in turn originated from the Samnites.34 According to Diodorus Siculus, the Brettians, who were fugitive servants sworn to robbing, became detached from the Lucanians in 356 BC.35 At that time they occupied Terina ...