![]()

1

Geographical Exploration by the Spaniards

Donald D. Brand

This and the following chapter do not incorporate a startling discovery, report a new document, or make a daringly different identification; they merely constitute a survey. But they do comprise a reminder of the great and courageous accomplishments of Iberians beginning long before the days of Tasman and of Cook. Furthermore, the eastern Pacific waters and coastlands are given more consideration than normally is the case with discussions of explorations in the Pacific Ocean. My chief concern has been the selection of events worthy of mention, the judicious choice among routes and identifications of discoveries made by other students in this field, and the indication (where advisable and possible) of the location of primary documents and reliable reproductions.

The way has been made easier by the compilations and collections of such authorities as Peter Martyr and Giovanni B. Ramusio, through James Burney and Martin Fernandez de Navarrete (hereinafter referred to simply as Navarrete), to the great historical collections published in Spain and Portugal in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, and the publications of the Hakluyt Society and the Linschoten-Vereeniging.1

To the critical judgement of such as Jean N. Buache, Burney, and Navarrete, I have added the modern scholarship of the various editors for the Hakluyt Society, as well as that expressed in other writings by such as José T. Medina, John C. Beagle-hole, Armando Cortesão, and the Visconde de Lagôa, and the expert identifications by many others including especially Henry B. Guppy, Carl E. Meinicke, Erik W. Dahlgren, Henry R. Wigner, H. E. Maude, and Andrew Sharp.2

For our purposes the Pacific extends from the Americas to the east coasts of Japan, the Philippines, Moluccas, and Australia, and from the Bering Sea to Antarctica. Such writers as Burney, Brigham, and Wroth3 have helped to establish these bounds. We are not concerned with the Asiatic waters along the western shores of the Pacific since there was little for the European to discover there. The Chinese, Japanese, Indonesians, Indians, Persians, and Arabs who navigated in these waters represented for the most part civilized peoples who made charts and kept records. The time span that we will attempt to cover is from 1511/13 to the nineteenth-century elimination of imperial Spain from the Pacific.

My procedure has been to read the published primary documents, with especial attention to editions and versions having editorial comment and notations, as well as the histories and other writings by individuals who had access to information no longer available—such as Oviedo, Barros, and Herrera. Also, I have examined most of the charts and maps available in reproductions, as well as a few unpublished charts, maps, and documents. Because I have personal acquaintance with only a very minor fraction of the coasts and islands of the Pacific, I have relied heavily on the identifications by Meinicke and by Sharp.4

There are many kinds of information which the reader has a right to expect, even in a brief survey such as this. Unfortunately, the data on the nature of the ships and their equipment, the crews, provisions and diet, and the daily regime of working the ships are uneven, usually scanty, and often almost totally lacking. This holds true also for the instruments and methods of navigation, and the resultant logs, accounts, and charts, as well as data concerning latitude and longitude, magnetic declination, winds, currents, soundings, morphology of coasts and islands, biota, ethnology, etc. There are three principal reasons for this situation. iMany things that were commonplace were not considered worthy of mention or description. Excessive nationalistic jealousy dictated policies of studied occultation of information. Apparently much material has been lost or destroyed through fire, earthquake, and flood, as well as by shipwreck, theft, improper storage, and by poor cataloging in archives, libraries, and museums.

However, there still exists a very large number of pertinent documents as yet unpublished in the Archivo General de Indias, Sevilla, as well as in the Archivo Na cional da Torre de Tombo, Lisboa, the Museo Naval, Madrid, the British Museum, London, the Vatican Library, etc.5 Here it should be pointed out, as Spaniards and Portuguese are doing increasingly, that the navigators and other officials of Spain and Portugal observed widely and made many detailed reports and charts—in fact, were specifically required to do so.6

NAVIGATION

The known extant documents provide very little information concerning the ships specifically involved in the exploration of the Pacific. Commonly we are informed only of the number of ships in an expeditionary fleet (usually ranging from two to five), the proper names (most commonly Santa María, Santiago, Victoria, Trinidad, San Pedro, San Pablo, San Francisco, Son Juan, and other names of saints), type of sailing vessel, tonnage, and the names of the captains and pilots. The type is given only by such designations as nave, nao, navío, and galeón (usually for the larger ships), caravela, bergantín, patax or patache, and bajel. Differences in local usages and changes of meanings through time make it extremely difficult to determine size, shape, rigging, and armament. For example, there seems to be no information available concerning the number of decks and masts and the rigging of the famous Victoria, which was the first ship to circumnavigate the globe.7 Even when tonnages are given, there is little agreement as to the conversion of the sixteenth and seventeenth century tcmeles de porte into modern tons of capacity. Most commonly 10 Spanish toneles de porte are considered to be the equivalent of 12 modern toneladas de capacidad.8

The methods and instruments of navigation and the details of working a ship are seldom noted in the available literature. Furthermore, most of the formal reports and "logs" of the expeditionary leaders and chief pilots—from Magellan to Malaspina— either are lost or unpublished. We can only assume that the methods outlined and the instruments recommended in the more popular manuals of the time were those actually employed.9 At the time of Magellan the chief navigational instruments consisted of the astrolabe for precision, the quadrant for less precise observations, the magnetic needle or mariner's compass (aguja de marear), dividers, and sailing charts (cartas de marear). The ballestilla or cross-staff does not appear in the Pacific until later in the century. The nature and development of the various techniques and instruments have been discussed by many historians and by some practical navigators, but unfortunately most of these writers have had one or another regional or national bias.10

Apparently all ships carried a supply of magnetized needles mounted on a card. By the time of Magellan, navigators were well aware of magnetic declination, and the various Spanish expeditions were instructed to make special observations on this matter. Both Portuguese and Spanish experts, such as João de Castro and Alonso de Santa Cruz, made maps showing magnetic declination. Santa Cruz corresponded with Antonio de Mendoza, the viceroy of New Spain, and the Mendocine expedi tions in the Pacific checked also on the problem of magnetic variation. Unfortunately, the extant "logs" give little information on these topics, and the results of observations on the various voyages must be sought in the writings of the stay-at-home experts in Europe.11

Speed and distance traversed were estimated on the basis of experience and current observations. Apparently there was no use of a corredera or "log" until some uncertain time late in the seventeenth century. Elapsed time was obtained from hourglasses or sandclocks and solar observations. Distances were stated in Iberian sea leagues (evaluated as about 3.43 nautical miles or roughly four English statute land miles), and grados or degrees (for Magellan equal to 16 2/3 marine leagues).

Latitude at sea was obtained almost exclusively by observing the altitude of the sun at local noon by astrolabe or quadrant and applying corrections from tables such as those of Zacuto. The range in error normally seems to have been between 10 and 60 minutes, usually toward the south, and rarely did the error amount to more than 30 minutes. This accuracy is remarkable when one considers the crudity of the instruments and the difficulties in making accurate readings on the deck of a relatively small ship. Despite many statements by chroniclers and historians concerning the obtaining of latitude from observations on the North Pole Star or two of the stars in the Southern Cross and other stars of the southern firmament, I have found no evidence for this in the available "logs" by Iberian mariners in the Pacific region. On occasion such observations were made on land, but at sea—if the sun were not sufficiently visible at noon—the pilot (who was the officer in charge of the details of navigation) would wait until the sun could be observed at noon, even though this might mean a wait of many days.12

Longitude never was determined accurately by the Iberian navigators in the Pacific region during the period of their great voyages, except on rare occasions and then apparently by accident. Spain did not use exact chronometers until 1774, and apparently no Spanish ship having such chronometers reached the Pacific region until about 1785. Among the many methods suggested for obtaining precise longitude, apparently those involving lunar distances and the observation of lunar eclipses were best. In both cases, however, the astronomical tables and the instruments were too poor during several centuries, and the conditions on shipboard were too unfavorable. Nevertheless, lunar eclipses—which at best were not frequent enough or visible in the appropriate regions—did provide the best approximations available for places in the New World such as Mexico City and Lima whence longitudes could be calculated for Pacific ports such as Acapulco and Callao.13

Precise determination of longitude had not been of much concern to the people of the Mediterranean and Atlantic coasts of Europe. It was not until the papal bulls and sanctions of 1452 to 1514, and the treaties between Spain and Portugal of 1479 to 1524, which ultimately established and recognized a Line of Demarcation between Portuguese and Spanish hemispheres, that an urgent need developed for precise determination of longitude. The primary Line of Demarcation came to be accepted as running near the present meridian of longitude 47° W. (Greenwich). In the controversy over which nation possessed or had access to the Moluccas it became of imperative importance to determine the location of the opposing meridian 180° around the globe. Ultimately Charles I of Spain (Emperor Charles V) effectively quitclaimed or sold his rights to the Moluccas 1524-29, although Spain retained the Philippine Islands which also were in the Portuguese hemisphere, and this particular problem became academic. Nevertheless, for years we are confronted with confused references to longitude based on the Line of Demarcation or on a too-frequently not specified primary meridian or línea meridiana. Frequently the Spanish astrologers (astronomers) used the meridian of Salamanca or of Toledo, while the navigators used Sevilla, Cádiz, and most frequently that of the Canary Islands.14

MAPS AND CHARTS

The sailing charts {cartas de marear) used by the Spanish navigators were prepared by cartographers in the Casa de Contratación in Sevilla, or by mapmakers under contract to the Casa de Contratacion. The sourcc of the data entered on these charts, which were specially prepared for each of the earlier expeditions, was theoretically and by law a master chart of the world known as the Padrón General de las Indias. This Padrón General was initiated about 1512, and presumably was kept up-to-date with the new data in the diarios and derroteros which had to be turned in after each voyage. For more effective presentation of data the master chart of the world was also kept on six regional charts having a larger scale. Eventually, three of these regional padrones generales covered the Pacific Ocean: one for the eastern Pacific and the coast from the Strait of Magellan to California, one for the northern Pacific from New Spain to the Philippines, and one for the region from Japan, China, the Philippines, and the Moluccas to the east coast of Africa.

Since practically all navigation to the Indies was monopolized or directed by the Spanish crown, there never was a need for a large number of sailing charts. Consequently, there was no necessity for a large edition of a sailing chart and all such charts were made by hand during the sixteenth ccntury and most of the seventeenth century. The upshot has been that nearly all the padrones generales and derived cartas de marear of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries have disappeared. This means that it is virtually impossible to trace the development of the map of the Pacific through official Spanish charts and maps.

Nevertheless, a considerable corpus of charts exists which embodies the results of Spanish voyages (Plates 19 and 20, facing this page). A relatively small number of

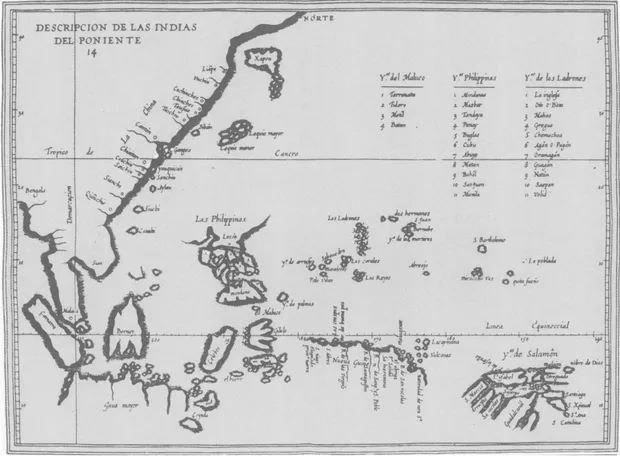

PLATE 19 "Descripcion [map] de las Yndias Occidentalis," in Antonio de Herrera y Tordesillas: see Note 24, Vol. 1, Plate 1, between pages 6 and 7.

PLATE 20 "Descripcion [map] de las Yndias del Poniente," in Antonio de Herrera y Tordesillas: see Note 24, Vol. 1, Plate 14, between pages 190 and 191.

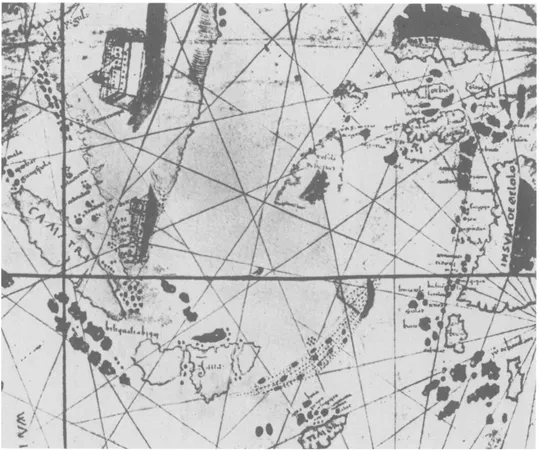

PLATE 21 The East Indies, in a manuscript map by Nuño García de Toreno, 1522, reproduced in R. A. Skelton: see Note 11 Fig 87 on page 141. (Courtesy of R. A. Skelton.)

PLATE 22 The East Indies, in a manuscript sea-atlas by Diogo Homem, 1558, reproduced in R. A. Skelton: see Note 11, Fig. 89 on page 142. (Courtesy of R. A. Skelton.)

these charts were made by officials (cartographers, cosmographers, pilots, et al.) who had been employed by the Spanish crown, such as Nuño García de Toreno (Plate zi), Diego Ribero, Alonso de Chaves, Sebastian Cabot, Pedro de Medina, Alonso de Santa Cruz, and Juan López de Velasco. Nearly all of the charts by these cartographers that have been preserved are of the "library type," and they probably were made for royalty, nobles, ec...