![]()

CHAPTER VI

THE AGE OF ANTHRACITE PIG IRON, 1855–1875

Business Conditions and Iron Production

As noted previously, the expansion in the production of anthracite pig iron between 1849 and 1854 was hastened by a period of business prosperity. These business conditions had been accentuated by the acceptance of the “railroad idea” by businessmen and the general public; people had finally been convinced that the building of railroads offered great profit opportunities.1 Discoveries of gold, improved banking facilities, and better credit instruments, as well as an increased flow of capital from England and Europe, provided the necessary finanacial means to facilitate this development. A continuing and relatively rapid influx of immigrants provided an increasing supply of labor for the construction of these railroads and the raising of many new factories and furnaces. But most important was the stimulating effect of the unprecedented expansion of railroads upon the country’s business activity. It enhanced the opportunities for other enterprisers and induced them to carry out the expansion of older ventures or develop new ones. Furthermore, this railroad development furnished the opportunity for locational, structural, and organizational alterations among particular firms, industries, and regions.

As business activity increased under the pressures of the railroad program, there were also a rapid price rise and growth in speculation, especially in land sales. This speculation was quickened by railroad development and an increase in the volume of agricultural exports, which makes it difficult to place the cause for the rise in land prices on any single factor. In 1854 a panic in the New York Stock Exchange brought the price rise to a halt and caused the failure of a number of business ventures. Shortly thereafter, however, this condition was remedied and once again there was a resumption of speculation which continued throughout the next two years.2

Railroad expansion and the increasing use of steam power in other industrial sectors of the economy called for a complementary growth in iron production. Consequently, throughout these years there was a continuing increase in the number of anthracite furnaces, and an ever-increasing amount of pig iron produced. By 1854 the annual production of anthracite iron had been raised to 339,435 net tons, and at the end of the next year the total output from anthracite furnaces exceeded the total product of the more numerous charcoal furnaces scattered throughout the nation. While the total domestic pig iron output was raised to 784,178 net tons, anthracite iron made up 48.6 percent of this total and charcoal iron 43.4 percent. The other 8 percent was produced by a few raw bituminous coal and coke furnaces.3

In 1856 there was a further extension of output from the anthracite furnaces as it moved up to 443,113 net tons.4 But this growth in production was halted quite abruptly by the panic of 1857 and the resulting depression.

During the year of the panic there was a sudden contraction of credit in the United States brought about by unfavorable specie flows and certain banking difficulties. Simultaneously, railroads, which had been extended beyond favorable market areas, found themselves with insufficient income to maintain their fixed costs. A number of these roads were unable to meet their interest payments, and in their failure they proceeded to drag into bankruptcy a number of banks which had become entangled in their railroad expansion program. Shortly thereafter, specie payments were suspended and railroad expansion declined precipitously. With the reduction in the growth of this industry, there followed a drop in output in related industries. Then, as the general price level dropped and the speculative atmosphere of the business world was replaced by an air of unrest, there was a further decline in business activity.5

These economic conditions prevailed for a relatively short period of time, but it was time enough to bring about the failure of approximately 5,000 business firms; a number of these firms had been in the iron smelting business.6

With the revival of the financial sector of the economy, more prosperous conditions returned to the rest of the economy and only slowed down briefly as open warfare between the North and the South commenced. Then, as the federal government’s expenditures increased, the earlier caution held by the businessmen in 1860 was swept away, production was increased, and income levels rose once again. For the next few years almost all sectors of the northern economy prospered under the favorable effects of the government’s expansionary fiscal policy which included heavy expenditures and borrowing.7

Throughout this period of conflict the iron industry brought forth an ever-increasing flow of metal so necessary for the waging of a war which had created numerous uses for iron in guns, rifles, ironclad ships, railroads, wagon wheels, various machines, machine tools, and hardware. This growth in demand carried pig iron prices upward, and, as prices rose, pig iron output was increased until it finally reached 1,135,996 net tons in 1864.8

With the close of the military conflict in 1865, there was a reduction in government expenditures and a contraction of greenbacks. These adjustments, plus the appearance of surplus revenues in the Federal Treasury and a business panic in England in 1866, served to push the general price level downward.9 Business activity, on the other hand, was not seriously affected by the economic readjustment, nor did the continuing but gradual decline in wholesale prices up to 1871 restrict the country from enjoying somewhat prosperous business conditions for the next seven years.

During that period which extended from 1866 to 1873 the economic activity of the nation was maintained at a prosperous level of activity by a very active program of railroad expansion. Geared to railroad expansion, the iron industry enjoyed a period of prosperity which stimulated a further growth in the number of furnaces and an increase in the number of tons of pig iron produced.

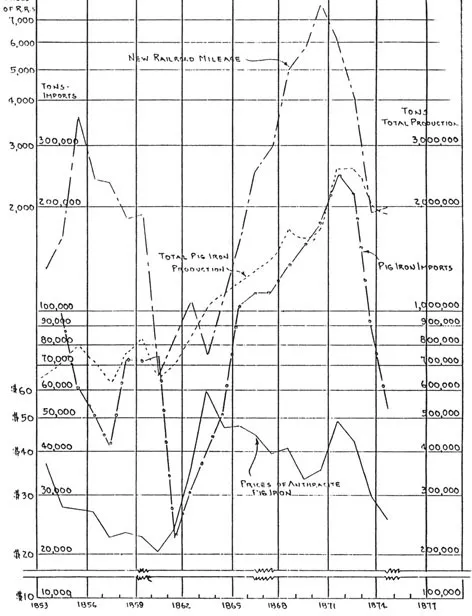

While railroad mileage was being doubled, from 36,827 miles in 1866 to 72,623 miles in 1874, the iron industry tried to meet the demand through the construction of new facilities, in some cases following the more modern techniques of furnace construction that had been developed in England in the 1850’s.10 Also, pig iron tonnage, which had dropped below 1,000,000 tons in 1865, was soon pushed beyond the peak period production of 1864 and was continually increased until it had reached a new peak in 1873 of 2,868,278 net tons.11 But the expansion in output was interrupted in 1873 as railroad construction fell once again when the flow of capital so necessary for its continuance was shut off by disturbed financial conditions.12 Pig iron, so essential in the production of rails, boiler plate, car axles, wheels, spikes, and other railroad equipment, had been smelted in ever-increasing quantities, but now, as the demand declined, output was reduced somewhat. However, at this stage of development the decline in pig iron production was not as precipitous as the drop in new railroad mileage. (See the chart on the following page.)

Pig iron prices, which had generally moved downward from 1864 to 1870, moved upward quite sharply in 1871 but then proceeded to drop again in 1873 and they were destined to fall to a low of $17.62 in 1878.13 As prices declined, iron production was reduced and the number of new blast furnaces being constructed fell to an extremely low level. Of the 713 completed blast furnaces of all types in existence in 1875, only 293 were reported in blast, and their total output was less than one-half of the estimated capacity of all the furnaces, being only 2,266,561 net tons.14

CHART I

RELATIVE CHANGES IN NEW RAILROAD MILEAGE, FIG IRON PRODUCTION PIG IRON IMPORTS, AND PIG IRON PRICES, 1854–77

Source: J. M. Swank, The American Iron Trade in 1876 (Philadelphia, 1876), passim.

From this brief discussion of the conditions of business between 1855 and 1875 it is quite evident that the pig iron industry was subject to extreme fluctuations in demand, a condition that arose from the extreme fluctuations in railroad activity which was somewhat speculative in nature. It must be recognized, however, that important changes had taken place in the iron industry during these years, for, despite the general downward movement of pig iron prices, there had been, until 1873, a continual expansion in the production of pig iron. The growth in production suggests that improvements, either in furnace practice or equipment, plus the improvements in the railroad network of the nation, must have reduced the unit cost of pig iron production and enabled ironmasters to obtain profits despite declining prices.

Tariff Policy and the Iron Trade

Nothwithstanding the continuing expansion of output in the iron...