- 220 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Technological Diffusion and Industrialisation Before 1914

About this book

Published in 1982 this is an introductory study of the international spread of modern industrial technology. The book considers the preconditions necessary for a country to adopt effectively modern industrial technology in the nineteenth century and the mechanisms by which this technology spread from one country to another. A global view is adopted and thus the book supplements others which are concerned with the industrial developmet of individual countries during the same period. It will be invaluable to anyone seeking an understanding of the early history of capitalism.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1TECHNOLOGICAL DIFFUSION AND NINETEENTH-CENTURY INDUSTRIALISATION

I

As a distinctive epoch in the economic organisations of society,modern industrial growth is dated from the eighteenth century, when its beginnings in western Europe, and more particularly in Britain, can first clearly be discerned. Its characteristic feature for industrialising countries was the application of factory production, based on the increasing use of modern scientific knowledge, to the satisfaction of human wants, and, compared with output increases experienced in previous times, its economic consequences were a rapid and sustained rise in real output per head of the population accompanied by revolutionary changes in the structure and organisation of the economy and of society.

Because the per capita output of a country is arrived at by dividing the country’s total output by its population, and because a country’s workforce consists only of those members of the total population available for employment, a rise in per capita output usually means an even larger rise in output per worker. This improvement in the efficiency or productivity of labour is made possible partly by the application of new knowledge to production, a fact that focuses our attention on the economic and technological transformation of society that has accompanied modern economic growth. This transformation has encompassed wide-ranging changes in the techniques of producing, transporting and distributing goods, in the types of output produced and consumed, and in the occupational and spatial distribution of productive resources. Together with attendant political and social changes modern economic growth in this sense embraces innovation in almost every aspect of individual behaviour and social organisation.

II

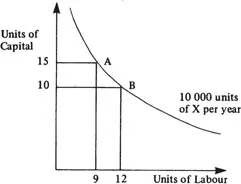

Amongst these innovations in economic and social behaviour and organisation, technological progress has a major role to play in bringing about the sustained increase in output per head that is the distinctive feature of modern economic growth. The technology existing at a given point in time sets limits on how much can be produced with given amounts of labour, capital and other productive resources. Given the level of technology, there is generally a wide range of possible methods of producing a particular good or service. Some require little capital and much labour, some require much capital and little labour; some are old techniques, some are new; and so on. Which of these technically feasible methods of production will be used—which one will minimise the costs of production—will depend upon the prices and therefore upon the available supplies, of the various factors of production.1 For example, if there were only two inputs, capital and labour, Figure 1.1(a) might show the production function for a particular product (X) at a particular point in time.2 As the diagram indicates, the given level of output can be produced with varying combinations of the two inputs depending upon the relative prices of labour and capital. Thus, if the supply of labour is relatively less abundant than that of capital, and its price therefore relatively more expensive than capital, we would expect this to result in the choice of a more capital-intensive method of producing X (combination A, say, rather than combination B).

Figure 1.1(a)

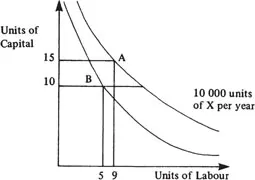

Figure 1.1(b)

Technical progress also results in a change in the combination of inputs required to produce a given level of output. In this case, however, as the result of the introduction of a new and superior method of production it becomes possible to produce the given output with a smaller amount of inputs than previously. This situation is depicted in Figure 1.1(b). Because of technological progress, the given output of X can now be produced using smaller amounts of both labour and capital. This represents an improvement in total resource productivity and it is shown diagrammatically by an inward shift of the production function from A to B. It is productivity improvements of this kind which were largely responsible for the sustained rise in per capita output and incomes characteristic of modern economic growth. This, in short, is the role that technological change has played in modern economic growth.3

Thus an immediate effect of technical progress was to change the combination of factors used in production. If the new technique was capital-saving, it resulted in a greater proportion of labour to capital per unit of final output. If it was capital-using, it resulted in a greater proportion of capital to labour per unit of final product. Over the long run, technical progress tended to be capital-using, since labour became the relatively expensive factor, and attempts were made to economise on its use. In one industry after another the capital coefficient increased. This increase in capital, in turn, raised the productivity of labour which was the root cause of rising real incomes. By enabling the production of the same output with a smaller input of resources, technical innovations set free resources that could then be used to increase the supply of the commodity in the production of which the innovation occurred, or to increase the supply of other commodities. In either case, the innovation increased real income by allowing a given supply of resources to be used efficiently.

III

The process of developing a modern technology and applying it to economic production has a distinctive pattern of its own, involving not only scientific discovery and invention, but also innovation, technical improvement and the spread of the innovation through extensive imitation. Whereas innovation, defined as the application of a new invention, whether social or technological, to economic production, is a key element in the process of economic growth, the rapidity of the spread of an innovation is obviously extremely important in determining how quickly a new technique is capable of raising the general level of productivity within an industry or within the economy as a whole, thus bringing about a rise in total and per capita real incomes.

When we look at the historical evidence of the spread of modern technology before 1914, apart from the fact that the diffusion was confined to select geographic areas, mainly in Europe and North America, and to a relatively small number of technical changes, the available evidence suggests that the diffusion of technology both across national frontiers and within nation-states was much faster in the nineteenth century and after than in any previous period in human history. The historical evidence also suggests that the spread of technology across national borders was much faster than its diffusion within national boundaries. Thus Watt’s steam engine, patented in Britain in 1776, was introduced into France in 1779, into Germany in 1788, and into Italy in 1816. Yet its use was not widespread in Britain until the 1830s and 1840s, and until even later in France, Germany and Italy. A similar experience is found in the spread of the techniques basic to the modernisation of the textile and iron and steel industries. Certain other technological developments of the nineteenth century, such as machine tools and the use of interchangeable parts, spread at an even slower rate, so that in these instances even larger technological gaps came to appear between nations.4 Moreover, in respect of some of the later technological developments, Britain, a pioneer in the field of early modern industrial technology, fell behind Continental and American innovators, and failed to adopt many of the new techniques readily. These observations raise a number of questions concerning the diffusion of technology. Why, for example, are some innovations diffused internationally faster than others? Why is diffusion often faster between countries than within them, and why do diffusion rates within countries differ? And, finally, why is one nation a leader in one area only to be a laggard in another? In order to answer questions such as these, what have to be studied are the conditions and circumstances that favour the diffusion of technical knowledge between persons and geographical areas, and the mechanisms facilitating the spread of modern industrial technology that have emerged in the recent past.

IV

As a first step in any study of this kind, it is obvious that the process of technological diffusion has to be studied in terms of two stages: the spread of technology between countries and its spread within a country. Fruitful analysis also demands the setting up of an appropriate framework within which such a two-stage study can be conducted. One such framework suggested in the recent literature on diffusion emphasises the fact that the diffusion process is essentially a learning process involving demonstration and imitative activities as its key elements. Learning by imitation is an intellectual feat of which, apart from man, only the highest vertebrates (e.g., monkeys, dogs, etc.) are capable. Demonstration and imitation form the basis of human development, both drives being innate in us. A diffusion model based on the concepts of demonstration and imitation has obvious attractions. However, another possible framework of analysis, which is the concern of this chapter, is that based on an analogy with the spread of a disease. If the manner in which a disease spreads is examined, it is found that epidemics and pandemics result from the conjunction of three essential conditions:

(i)an available store of organisms causing the disease;

(ii)effective transmission of these organisms in sufficient numbers;

(iii)other individuals with tissues susceptible to the organisms.

Given the existence of sources of infection, the spread of a disease can be broken down into two distinct proceses: the transmission process, which is concerned with the mechanisms whereby diseases are transmitted between persons and carried over long distances. In epidemiology the mechanisms involved are referred to as the vectors or carriers of the disease. The contagion process, on the other hand, examines the spread of a disease from the point of view of the susceptibility of the individual to the disease. In other words, whereas the transmission process is concerned chiefly with the methods of spread of disease between infected and non-infected individuals, the contagion process involves a study of the determinants of the rate of spread of the disease within a newly-infected population. In respect of the latter problem, it should also be noted that to speak of an individual’s susceptibility to infection implies, as its alternative, the existence of different degrees of human resistance to the spread of disease.

When we turn to the fields of economics and economic history and examine the recent literature on technological diffusion in terms of the framework just outlined, we find that the problem of technological diffusion has been studied mainly at the micro-economic level, and that research has been largely concerned with a study of the rate of spread of modern technology.5 These studies tend to show that the diffusion of new techniques is generally a slow process, and that the rate of diffusion varies widely between countries and regions within countries. They also tell us much about the economic and technical determinants of technological diffusion at the national and international levels. Broadly speaking, these determinants reflect either market conditions or supply conditions of complementary factors of production in the country or region receiving the new technology, and it is perhaps the supply side of the economy that has received most of the treatment in the literature.

V

Turning to the international diffusion of technology, it is a well-established fact that the international economic system played a major role in promoting the spread of modern economic growth. The flows of trade, capital and labour which linked countries together were not only the means whereby the benefits of economic growth in the form of higher real incomes, could be transmitted from country to country, but they were also the mechanism by which the technological and social innovations which are the essence of modern economic growth could be diffused. I...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- PART ONE: THE PROCESS OF INDUSTRIALISATION AND THE DIFFUSION OF TECHNOLOGY

- 1. Technological Diffusion and Nineteenth-century Industrialisation

- 2. THE SPREAD OF INDUSTRIALISATION BEFORE 1914

- PART TWO: THE SPREAD OF MODERN INDUSTRIAL TECHNOLOGY: PRECONDITIONS

- 3. THE SPREAD OF MODERN AGRICULTURAL TECHNIQUES BEFORE 1914

- 4. The Size of the Market

- 5. Saving and the Rate of Capital Accumulation

- 6. The Financial Environment

- 7. Industrialisation and Labour Supply

- 8. Resource Endowment and Industrialisation

- 9. The Technical Factor in Industrialisation

- 10. Industrialisation and Entrepreneurship

- Part Three: The Spread of Modern Industrial Technology: Mechanisms

- 11. The International Economy and the Diffusion of Modern Industrial Technology

- 12. The Competitive Market Economy

- 13. Investment Banks and Industrialisation in the Nineteenth Century

- 14. Industrialisation and the State

- 15. Industrialisation After 1914

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Technological Diffusion and Industrialisation Before 1914 by A. G. Kenwood,A. L. Lougheed in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Economics & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.