This is a test

- 206 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Originally published in 1973, The Welfare State traces the historical roots of the Welfare State and considers the problems to which it gives rise, especially in the allocation of resources. It focuses on the economic issue of meeting needs with scarce resources and compares the British experience with that of other countries. It sets out the pattern of the social services since Beveridge and summarises the criticisms levelled at them. It considers the economic issues involved and provides a straightforward presentation of the available policy choices, the discussion poses a direct comparison with other countries. The book offers an overall conspectus of current policy issues against the historical background from which they arise.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Welfare State by J.F. Sleeman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter One

WHAT IS THE WELFARE STATE?

The phrase ‘the Welfare State’ has passed into our common language, often without much thought about what it really means. According to one recent authority,1 it was probably first used in print by Archbishop William Temple, in his pamphlet ‘Citizen and Churchman’, published in 1941, in which he says, ‘In place of the concept of the Power State we are led to that of the Welfare State.’ Whatever its origins, it came into general use in the years after 1945 to describe a phenomenon which everyone recognized, when the Government’s responsibility for the provision of social services was extended. With the development of National Insurance, National Assistance and Family Allowances, with the setting up of the National Health Service and the extension of public educational provision, with the growth of welfare services for old people, children and families in trouble, and with the spread of the public provision of subsidized housing, it was generally felt that we had a new kind of State, a Welfare State. No longer was the State merely the policeman who kept law and order, or the arbiter who settled disputes and upheld the sanctity of contracts. No longer was its concern only to relieve the most acute cases of need or inequality. Its business was now positively to promote the welfare of all its citizens.

Unfortunately, the concept has also become embroiled in political controversy. For some it is the very symbol of the role which the State should play in modern society, in which participation in the social services should be one of the rights and duties of citizenship; the services provided by the Government to promote the common welfare of all the citizens should also be constantly improved and extended. Hence it is to be defended against all attacks by reactionaries. For others, it is the symbol of ‘feather-bedding’, of a tendency to provide help to people irrespective of whether they need it or not, an excessive care for the needs of all which is in danger of sapping self-reliance and initiative. Hence as incomes rise it should be expected to wither away, and people should become more able to provide for themselves.

Most people probably fall somewhere between these two extremes, accepting the benefits which the services provide for them, thankful that we are now able to meet the needs of the less fortunate so much better than we could in the past, uneasily aware of the many gaps which still exist in our services, and yet perhaps a bit apprehensive whether perhaps we have gone too far in the direction of feather-bedding. To examine the historical developments which lie behind the present forms which our welfare services take will be part of the business of this book; in so doing, it will look at the ideals which underlie them and the effects which their working is liable to have on the economy. Thus we shall attempt to throw some light on this controversy, and draw some conclusions about how the services may be expected to develop in the future. But first we must see how spending on the social services has grown over the years.

THE RISE IN PUBLIC EXPENDITURE, ESPECIALLY ON THE SOCIAL SERVICES

Comparisons of the real national product of a country at widely separated periods are difficult, because there are so many changes in the types and qualities of the goods and services produced. We have motor cars, television sets and washing machines today, unknown or virtually unknown at the turn of the century. We eat different kinds of food and we have them increasingly pre-packaged and prepared. We tend to buy them at the supermarket instead of at the family grocer’s, and we do our washing at the launderette instead of employing a washerwoman. Electricity, a luxury in 1900, is now an everyday necessity. On the other hand, we no longer use candles or horse buses, and domestic service has become a rare luxury. Nevertheless we can say in rough terms that the average Briton is perhaps twice as well off in the 1970s as he was in the early 1900s, in the sense that real national product per head is about double today what it was in 1900.

Of course the product is not shared out equally. Kuznets quotes the following figures for Britain, based on income tax returns.2

| 1913 | 1938 | 1949 | 1957 | |

| Percentage of income before tax received by: | ||||

| Top 5 per cent of income units | 43 | 29 | 23.5 | 18 |

| Top 20 per cent of income units | 59 | 50 | 47.5 | 41.5 |

| Percentage of income after tax received by: | ||||

| Top 5 per cent of income units Top 20 per cent of income units | not available | 24 46 | 17 42 | 14 38 |

These figures would imply a considerable reduction of inequality, especially after deduction of income and surtax. In fact, their significance is problematical; those people with the highest incomes have a number of ways of reducing their taxable incomes relative to their actual spending power, through settlements, trusts, gifts, insurance, capital gains and so on; large numbers of the lowest incomes are not subject to assessment and so escape accurate record. What is clear, however, is that there has been a growing redistribution of income between the working population and the non-working population, through taxation and spending on social security benefits to the old and the sick, and through education and health services.3 Also, improved educational opportunities and health facilities make it easier for more people to enter the better-paid white collar and professional occupations, in which the demand for labour has been growing anyhow.

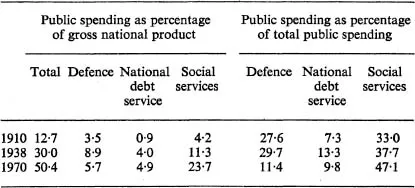

In any case, the rise in the real national income has been accompanied by a massive growth in the share of it passing through the hands of the public authorities. In the early 1900s they spent only some 10 to 12 per cent of the national product; of that, more than a quarter went on defence and almost a tenth on the service of the National Debt, which was largely the cost of past wars. Between a quarter and a third went on social services, and that was spent almost entirely by the local authorities.

By the early seventies, in contrast, the public authorities together were spending 40–50 per cent of the national product, about half in services in kind, such as defence, education or medical services, and about half in transfers of cash, for example social security benefits and interest on Government securities. Defence now takes only some 11 per cent of this total, or 6 per cent of the gross national product. Interest on the National Debt accounted for 10 per cent of total public spending, transferring some 5 per cent of the national product from taxpayers to holders of Government and local authority securities. The social services, including housing, accounted in 1970 for 47 per cent of total public spending, or 23½ per cent of the gross national product, including current services in kind, like education and medical treatment, capital expenditure on houses, schools and hospitals, and transfers such as social security benefits or housing subsidies. Table 1 summarizes the position; further details are given in the first section of Chapter 7.

TABLE 1 The growth of social service expenditure in Britain

Source: Peacock and Wiseman, The Growth of Public Expenditure in the United Kingdom (Allen and Unwin, 1967) and National Income and Expenditure (HMSO, 1971).

The exact relationship between the growth of the national product and the growth of public spending, particularly on social services, is a matter of some controversy, which we must consider in more detail later. Undoubtedly it is a two-way relationship. As the country becomes better off, the evils of poverty and lack of opportunity stand out more clearly, and the community takes a political decision to spend more on providing for the needs of the less well off. An urbanized, industrial community also has a greater need to spend on public services than a rural, agrarian one, since town life demands public health and welfare services for civilized living, and an industrial society needs a higher level of formal education. On the other hand, expenditure on education and health services and, in varying degrees, many of the other social services are also a form of investment in human capital. This in turn bears fruit in greater productivity and a more rapid growth of the national product. Attempts to measure the rate of return on educational expenditure in the United States, for instance, using expected additional life-time earnings achieved by those attaining higher levels of education, suggest that it is comparable to the return on investment in physical capital.4

A CHANGE IN THE CONCEPT OF THE STATE AND ITS FUNCTIONS

Whatever may be the causal relationships, there is no doubt that we have seen a change in the concept of the role of the Government in the community which is one of kind rather than merely of degree. The term ‘Welfare State’ reflects an attitude towards the State, which sees it as a positive agent for the promotion of social welfare. In this it can be contrasted with the laissez-faire ideal of the State rather as a policeman or arbiter. The believers in laissez-faire saw the functions of the Government as being primarily those of protecting the community against external attack, maintaining internal law and order and guaranteeing contracts; thus it provided a framework within which private enterprise and the free market could work. Beyond this, they only recognized a very narrow range of public services as being justified on the grounds that private enterprise could not provide them. These included a minimum provision for the relief of the destitute, or the undertaking of public works such as harbours, canals or lighthouses. In general, they believed that public enterprise was likely to be inefficient and wasteful and that taxation was a necessary evil, draining away money which would be better left to fructify in the pockets of the people.

In contrast to this laissez-faire attitude, we now accept that social welfare demands a much wider and more pervasive range of Government activity. Not only should the Government provide social services, such as social security, medical treatment, education, welfare facilities and subsidized housing, but these should go beyond the provision of a bare minimum towards ensuring that all have equal opportunity, so far as the country’s resources allow. There is difference of opinion as to how this can be most effectively done and what degree of public provision it should involve, relative to private, but the principle that this is a proper public concern is generally accepted. It is also generally accepted that the Government has an obligation to steer the working of the market economy in the directions considered to be socially desirable. Fiscal policy and monetary policy should be used to combat unemployment and inflation and promote steady growth. Encouragement should be given to types of investment thought to be desirable, by means of investment allowances and grants. Help should be given in developing new industries in those areas of the country which are unduly dependent on declining industries and hence lagging in growth and incomes. The Government should intervene in some cases to prevent the restriction of competition by monopolies and trade agreements, where greater competition is thought necessary for economic efficiency; in other cases, it should promote mergers of firms into larger units, where this is necessary for effective competition in world markets. In a crowded country like Britain, moreover, control of the physical environment becomes ever more necessary, if people are to be decently housed, industry is to be located where it can grow with best advantag...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- 1 What is the Welfare State?

- 2 The Origins of the Modern Welfare State

- 3 Development of the Social Services, 1900-1948

- 4 The ‘Beveridge Revolution’

- 5 General Description of the Post-1945 Welfare State

- 6 The Limitations of the British Welfare State

- 7 The Economics of the Welfare State

- 8 International Comparisons

- 9 The Future of the Welfare State

- Bibliography

- Index